Advances in Diabetes & Endocrinology

Download PDF

Review Article

Reimagining Empowerment: A Critical Review of Empowerment Theory in Diabetes Research

Walker HR1* and Litchman ML2

1Medical Group Analytics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, USA

2College of Nursing, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, USA

*Address for Correspondence:

Walker HR, Medical Group Analytics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT

84102, USA; Phone: 530-755-7673; E-mail: heather.walker@hsc.utah.edu

Submission: 08 June, 2022

Accepted: 06 July, 2022

Published: 07 July, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Walker HR, et al. This is an open access article

distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Diabetes, well documented as a complicated condition, has

been the focus of self-management studies for over three decades.

Empowerment theory has co-developed within diabetes literature

at the same time. However, this literature lacks a core and standard

definition, which has led to incongruencies in theory and relative

terminology. In this critical review, the construct of empowerment in

diabetes literature is dissected and examined. Prominent measures

and methods are problematized to highlight their overreliance on

individual behavior rather than systemic social change. Current

interventions targeting empowerment focus almost exclusively on

individual behavior-change, inadvertently suggesting that the location

of the problem of poor management lies within the abilities, attitudes,

and beliefs of individuals. This paper argues that there has to be a

socially-based power-related shift from one group to another in the

process of empowerment for its construct to be complete, and that

the ultimate agent of change must shift from the patient to systemic

barriers in their way. Examples of online patient community-generated

definitions, resources, and practices of empowerment are highlighted,

leading to an argument that researchers and healthcare providers

ought to add nuance to the construct of empowerment by weaving

in community and systems levels change goals.

Keywords

Diabetes; Empowerment; Change; Critical review;

Community-based methods, Participatory design, Systems change

Introduction

Diabetes is a condition that seeps into life physically, mentally,

emotionally, and socially. As such, there is an impact on sense of

self among people with diabetes (PWD) as one must consider their

day-to-day activities, social positioning, environment and economic

factors. There are multifarious stigmas attached to diabetes that

color the ways in which one develops and adjusts their self-concepts.

Despite the deep impact diabetes is known to have on identity, the

psychosocial impact of diabetes has only been taken up as an area

of study since the early 1990s, after a major shift in the treatment of

diabetes occurred.

In 1993, a groundbreaking study, the Diabetes Control and

Complications Trial (DCCT), was published. For the first time, there

was significant evidence linking tight diabetes self-management

to decreased incidence of diabetes-related complications [1]. For

healthcare providers, this study redefined the goals of practice and

treatment. It called for increased diabetes patient education with a

focus on self-efficacy and activation. For patients, the DCCT drastically

transformed the obligation and responsibility of risk mitigation from

being provider-based to being patient-based, increasing the psycho

social burden of diabetes on the patient [2]. For example, having a

sense that one can cause or avoid their own complications has been

linked to higher rates of stress, guilt, and distress within diabetic

populations [3]. Today, the individualized challenges of diabetes

extend far beyond the practice of doing self-management, to the art

of coping with them.

Individuals with diabetes must engage in daily self-management

practices, such as physical activity, healthy diet, taking medications,

stress reduction, and sleep. For those on insulin, it is the gold standard

to calculate insulin doses based on insulin-to-carbohydrate ratios and

insulin sensitivity ratios with every meal and snack. Diabetes calls for

advanced and thorough planning with day-to-day activities, including

travel, driving, sleeping, eating, exercising, etc. Our previous research,

further, suggests that diabetes requires individuals to shape their sense

of self around the demands of the illness – requiring they incorporate

descriptors like planner and responsible into their self-concepts [4].

Additionally, accounting for the time PWD spend thinking about

diabetes [5], it is no surprise that studies of diabetes management

have moved toward the realm of distress, depression, empowerment,

activation, and self-efficacy.

This movement in the research and treatment of diabetes toward

the psychosocial most heavily relies on nurturing patients’ selfefficacy.

Self-efficacy, a concept developed by noted Psychologist

Albert Bandura, is a person’s belief in their own ability to control their

life circumstances and effect change through behavior modification

[6]. Self-efficacy relates to a person’s ability and willingness to enact

behavior modifications toward disease management betterment.

Self-efficacy is a hyper-individualized approach to diabetes care and

treatment because it implies that control is ultimately a matter of

willingness to perform a set of behaviors that will lead to change. This

approach however, fails to capture or critically reflect on the social,

political, and economical considerations people with diabetes face.

Self-efficacy as a construct closely parallels empowerment as it is most

generally applied to diabetes in research and healthcare. This paper

critically reviews the construct of empowerment in diabetes literature

and argues for a more sociopolitical approach.

Empowerment in Diabetes Research

Empowerment blossomed in the diabetes space prior to the

DCCT, however, the DCCT amplified its construct. In 1991, diabetes

researchers introduced the need for a shift toward empowerment

within diabetes care arguing that the traditional medical model relied

too heavily on health care providers as decision-makers [7]. Originally,

the construct of empowerment was described as a form of accepting responsibility for oneself and one’s own health [7]. However, over

time, the common constructs of empowerment in the literature have

shifted and now represent several factors related to who is responsible

for empowerment, what is required for empowerment to take place

(e.g. a process, a treatment, etc.) and how empowerment might

occur. This article explores these areas and calls for a reimagining

of empowerment in the diabetes space. As an entry point into these

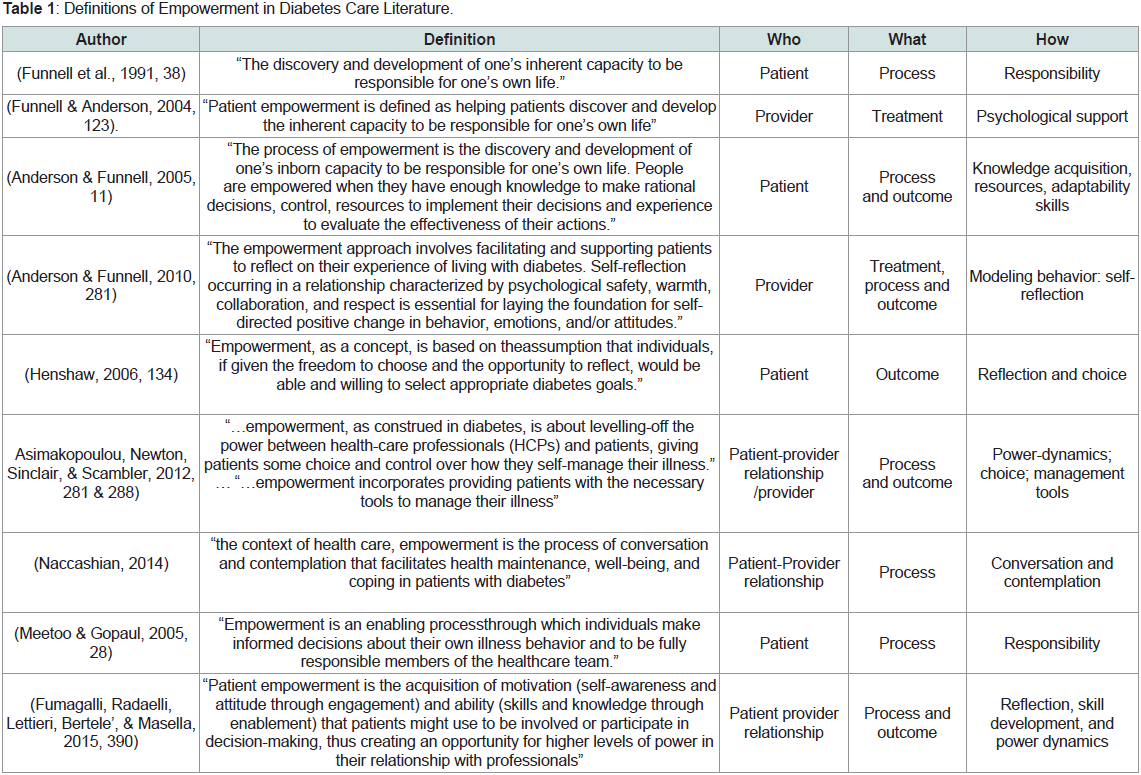

ideas, Table 1 provides definitions from leading and top cited works

on diabetes empowerment (Table 1).

The construct of “who” in empowerment:

Historically, health researchers have viewed the person

responsible for empowerment to be focused on the patient, provider,

or the patient-provider relationship (Table 1). This posits that in order

for patients to be empowered, they are to become knowledgeable

[13], reflective about their willingness to engage in diabetes selfcare

[Table 10], and choose to be responsible by engaging in diabetes self care

activities [7,11]. Providers, on the other hand, are to empower

patients by providing psychological support [8], facilitating patient

self-reflection [9], and providing diabetes self-management tools [15].

Within a patient-provider relationship, empowerment can take place

if power hierarchies are reduced [12,15], and knowledge is effectively

transferred [12].While the literature varies in stating who is responsible for

enacting empowerment, the onenessonus is always ultimately on the patient. For example, the provider can give patient tools, but the patient

has to choose to use them beyond the walls of the clinic or research

site. Providers can hand over decision-making power to the patient,

but the patient still has to use that power to weigh self-management

options and actively choose the path best suited for them. The illusory

variance in the construct of ‘who ‘in the diabetes empowerment

literature may be representative of a social phenomenon contributing

to worse health outcomes in diabetic populations.

In one community-based study, diabetes incidence was found

to be constructed as a failure of the individual. Staff persons in at

the Community Health Center of study believe that diabetes is a

signal of a defective individual who is ignorant of self-care strategies

necessary to manage diabetes effectively [16]. Perhaps more telling,

patients expressed a tendency to internalize the attributions made

by staff persons. Patients themselves believed that if they were better

educated had more education and made “better” choices, their health

would be better. This form of internalized ableism, which can be

theoretically linked to the treatment philosophies and practices used

in diabetes care today, is particular particularly insidious within

diabetes populations because of the way diabetes is associated with

poor choices [17]. When prompted during interviews with questions

related to structural inequalities, participants in the Chaufan study

reverted back to individual attributions and solutions. This implies

that both patients and community-service staff function under a

belief that the “proper locus of intervention” ought to occur at the

individual rather than the social level [16]. When only individualized approaches to diabetes empowerment are taken, social and structural

inequalities and possibilities for social change are ignored. The

problem remains then within the individual seen as responsible for

any potential change: the patient [16].

The construct of “what” in empowerment:

The mechanism through which empowerment may occur varies

throughout the literature. Some studies describe empowerment as

an outcome which can be measured and treated clinically [10,13,18].

The most common research tool used to measure empowerment as

an outcome is the Diabetes Empowerment Scale (DES). Researchers

who developed the DES describe the purpose of the empowerment

approach to treatment “as helping patients make informed choices

about their diabetes self-management” [19]. The scale is designed to

measure a patient’s behavior change and thus has been used primarily

as a pre-and post- intervention measurement. Topics covered in the

scale relate to three categories: 1) managing the psychosocial aspects

of diabetes; 2) assessing dissatisfaction and readiness to change; and 3)

setting and achieving diabetes goals [6]. The Diabetes Empowerment

Scale has been translated into several languages and into short form

as recently as 2021, suggesting it is still being used on a global scale

[19-22].Though the tool is called an empowerment scale, the journal

article introducing it describes it as a measure of self-efficacy,

indicating a conflation in terminology [6]. The questions used in the

scale focus on the patient’s belief in their ability to identify and act on

diabetes-related issues as well as their attitude toward living with the

daily requirements and demands of diabetes. Though the validity and

reliability of the scale have been confirmed, classifying the DES as a

psychometric survey, the researchers do not measure or comment on

the social validity of the scale.

Social validity can be defined as “the extent to which potential

adopters of research results and products judge them as useful and

actually use them” [22]. Though the tool is called an empowerment

scale, the journal article introducing it describes it as a measure of

self-efficacy, indicating a conflation in terminology [6,19]. The

questions used in the scale focus on the patient’s belief in their ability

to identify and act on diabetes-related issues as well as their attitude

toward living with the daily requirements and demands of diabetes.

Though the validity and reliability of the scale have been confirmed,

classifying the DES as a psychometric survey, the researchers do not

measure or comment on the social validity of the scale.

Social validity can be defined as “the extent to which potential

adopters of research results and products judge them as useful and

actually use them” [23]. In this way, potential adopters can mean

fellow researchers, members of the population of study, healthcare

providers, and so on. Though the DES has been used in many

studies since its publication in 2000, the social validity to the patient

population remains unexplored. Methodologically, this means we

have yet to develop a meaningful understanding of the relevance and

significance of the results of this scale to diabetic populations and

service organizations serving them. Furthermore, we do not know

yet of its usability by and for community members, which has been

taken into consideration by some health researchers [23,25]. It may

be the case that members of diabetes communities would want an

empowerment scale such as this one to also capture aspects of social and community empowerment. However, if they are not brought

into the research process beyond piloting the survey for validity and

reliability purposes, researchers will remain ignorant of this gap.

Empowerment has also been described in the literature as a process

of becoming empowered. Studies that take this approach either argue

that empowerment happens within the effort made to reach diabetes related

goals, but is not necessarily an end goal in itself [11,24,25],

or that empowerment is an unfolding internal process leading to a

state of being [26]. Studies that describe empowerment as a process

require healthcare provider input through education, therapy, or skill

and knowledge transference. Though the construct of empowerment

as a process revolves around individual patient growth, it suggests

that said growth cannot occur without provider involvement. This

philosophical incongruency defies the underlying aim of current

empowerment constructs arguing for self-directed patient change

studies that take this approach argue that empowerment happens

within the effort made to reach diabetes-related goals, but is not

necessarily an end goal in itself [11,24,25], or that empowerment is an

unfolding internal process leading to a state of being [28].Studies that

describe empowerment as a process require healthcare provider input

through education, therapy, or skill and knowledge transference.

Though the construct of empowerment as a process revolves around

individual patient growth, it suggests that said growth cannot occur

without provider involvement. This philosophical incongruency

defies the underlying aim of current empowerment constructs,

another problematic aspect of the way diabetes empowerment is

constructed in clinical research.

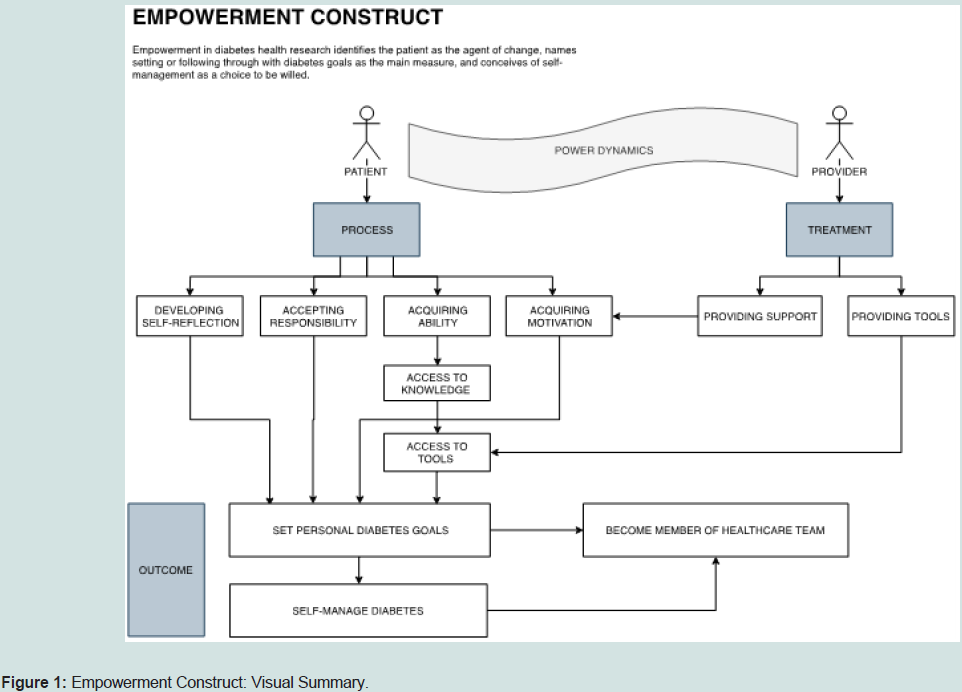

To better link the way aforementioned definitions and uses of

empowerment within diabetes literature, we developed a flowchart

of responsibility and outcome. The flowchart in Figure 1 visually

summarizes our critical review of the construct of empowerment and

its definitional components within diabetes literature.

To drive this point home, of the masse of literature covering

empowerment within the context of diabetes, few studies offer

definitions of the concept. These studies seem to take the position

that the concept of empowerment is a given, and does not need to

be thoroughly defined [27-30]. As further evidenced by our critical

review here, the construct of empowerment is not a given. There

is no universal or standard understanding or conception of what

empowerment is how to harness it, or what it looks like when it is

intervened on.

When considering what empowerment is, the literature is

evermore wrought with incongruencies and discrepancies. There

are also gaping holes which are made deeper upon reflection of the

construct of how in diabetes empowerment literature.

The construct of “how” in empowerment:

Thematically, when the definition of empowerment implicates

the patient as the agent of change, the mechanisms revolve around

individual internalization processes like self-reflection and accepting

responsibility [7,10,11,13,,24]. To drive this point home, despite

ample research articles covering empowerment within the context

of diabetes, few studies offer definitions of the concept. These studies

seem to take the position that the concept of empowerment is a given,

and does not need to be thoroughly defined [29-32]. As further evidenced by our critical review here, the construct of empowerment

is not a given. There is no universal or standard understanding or

conception of what empowerment is, how to harness it, or what it

looks like when it is intervened on.When considering what empowerment is, the literature is

evermore wrought with incongruencies and discrepancies. There

are also gaping holes which are made deeper upon reflection of the

construct of how in diabetes empowerment literature.

The construct of “how” in empowerment:

Thematically, when the definition of empowerment implicates

the patient as the agent of change, the mechanisms revolve around

individual internalization processes like self-reflection and accepting

responsibility [7,10,11,13,26]. When the definition of empowerment

implicates the provider as the agent of change, the mechanisms

revolve around modeling behaviors, psychological support, and

providing management tools [8,9]. And lastly, when the definition

of empowerment implicates the patient-provider relationship as the

agent of change, the mechanisms revolve around power dynamics,

self-reflection, and skill development [12,18,25,27]. The way in

which empowerment occurs, then, is described as dependent upon

the identified agent of change, a facet of the construct which we’ve

problematized hit her to here.Problematizing the Construct of Empowerment:

Empowerment has been problematized on the basis that use of

the term is confounded within the literature with patient activation,

patient engagement, patient participation and patient enablement [12].

Fumagalli et al. further argues that empowerment is defined across

studies as an active patient behavior, as an achievable state of being,

and as a process of transformation, much of which our critical review

discusses. This inconsistency in the literature leaves the construct

wrought with apertures, both theoretical and practical. The study

concludes with a provocative proposal: could empowerment be an

illusion of power that ultimately maintains top-down power dynamics

present within the parlance of clinical interactonsinteractions? [12].

Considering that, across definitions, empowerment is ultimately the

responsibility of the patient, this provocation merits further critical

consideration.When it comes to active participation in one’s own care, this

literature is saturated. However, there is a dearth of literature related

to social and political empowerment. What would sociocultural and

sociopolitical research on diabetes an empowerment look like? How

could methods and measures be modified to capture a more nuanced

construct of empowerment which takes into account considers

social conditions and positioning, stigma, economic, and capital

resources? Where could researchers go for guidance on incorporating

sociocultural and sociopolitical facing elements to their diabetes

empowerment research?

Empowerment as a Social Process:

As previously mentioned, community-oriented conceptualizations

of empowerment are blatantly missing from the literature on diabetes

and empowerment. Empowerment, when conceptualized as a social

process rather than an individualized one, takes on a more critical and

nuanced meaning.Disability activist and scholar, Jim Charlton’s book, Nothing About

Us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment, presents

some of the theory behind the concept of empowerment as a social

processs [31,33]. To introduce and contextualize the book, Charlton

describes a paradigm shift which occurred that critically opened

up the study of disability. He calls this shift “a historical break with

traditional perception of disability as a sick, abnormal, and pathetic

condition” [10,33]. This historical shift, in part, resulted in disabled

activists starting the Disability Rights Movement. To Charlton and the

international disability rights advocates he interviewed in the writing

of his book, “empowerment must translate into a process of creating

or acquiring power” for the collective [33]. That is, there has to be a

socially-based power-related shift from one group to another in the

process of empowerment. In this way, empowerment is not about an

individual, but about the social positioning of the group as a whole.

In diabetes, there is no shortage of stigma and prejudice creating

and maintaining the social positioning of people with diabetes as an

inferior class [17]. The attribution of both diagnosis and poor self-management

to laziness is but one example [16,32]. That is, when a

person is diagnosed with diabetes, they are categorized as one who

does not take care of themselves. In a recent study, it was found

that those who report having “poor diabetes control” experience

disproportionately more social stigma from family, friends, and the

public [33]. Similarly, in one Hong Kong-based study, participants

reported that due to perceived social stigma, they felt obligated to

only perform diabetes-related tasks in private, which then led to the

omission of blood glucose testing and insulin administration before

group meals [16,34]. That is, when a person is diagnosed with diabetes,

they are categorized as one who does not take care of themselves.

In a recent study, it was found that those who report having “poor

diabetes control” experience disproportionately more social stigma

from family, friends, and the public [35]. Similarly, in one Hong

Kong-based study, participants reported that due to perceived social

stigma, they felt obligated to only perform diabetes-related tasks

in private, which then led to the omission of blood glucose testing

and insulin administration before group meals [36]. Together, these

studies demonstrate a bi-directional relationship between perceived

social stigma and self-management.

Socially, the interventions for improving self-management

through empowerment principles, like action-planning, goals setting,

and problem solving [35,36], identifying and addressing personal

challenges [37], and integrating coping strategies [38], actually work

to authenticate the stigmatization faced by people with diabetes. That

is, it suggests that the location of the problem of poor management

lies within the abilities, attitudes, and beliefs of individuals. When our

empowerment research fails to account for the social and community

aspects of power, they also fail to challenge dominant discourses

and inequities actively reproducing power differentials. This stigmareproducing

dynamic has been shown to negatively impact research

recruitment in minority populations, as well [39].

Calling for More Participatory Methods:

In part, previous research on empowerment has failed to address

social concepts of power and positioning because the methods and

measures used to explore it have been largely top-down. To reiterate: the

dominant construct of empowerment understands self-management as a set of strategies that once adopted will move a patient to change

their health behaviors. However, as is noted in sociocultural-focused

diabetes studies, self-management does not happen in a vacuum

[16,40,41]. Socially, the interventions for improving self-management

through empowerment principles, like action-planning, goals setting,

and problem solving [37,38], identifying and addressing personal

challenges [39], and integrating coping strategies [40], actually work

to authenticate the stigmatization faced by people with diabetes. That

is, it suggests that the location of the problem of poor management

lies within the abilities, attitudes, and beliefs of individuals. When our

empowerment research fails to account for the social and community

aspects of power, they also fail to challenge dominant discourses

and inequities actively reproducing power differentials. This stigma reproducing

dynamic has been shown to negatively impact research

recruitment in minority populations, as well [41].Calling For More Participatory Methods:

In part, previous research on empowerment has failed to address

social concepts of power and positioning because the methods

and measures used to explore it have been largely top-down. To

reiterate: the dominant construct of empowerment understands

self-management as a set of strategies that once adopted will move

a patient to change their health behaviors. However, as is noted in

sociocultural-focused diabetes studies, self-management does not

happen in a vacuum [16,42,43]. As such, the dominant construct

of empowerment and the ways in which we study it must shift to

better reflect the rich lived experiences of this population. From a community perspective, being empowered is politicized when the

individual focus expands into the public/community sphere [4].

Empowerment, therefore, is an emancipatory construct when rooted

in community experience. Where we see overlap between clinical and

community-based definitions and constructs of empowerment comes

by way of the central aim: mobilization.Within diabetes online communities (DOC), a user-generated

term that encompasses people affected by diabetes who engage

in online activities to share experiences and support in siloed or

networked platforms[42], mobilization looks like social media-based

social movements through hashtags, the formation of grassroots

organizations, and public outcries in response to stigmatizing media

portrayals of diabetes.

While clinical and behavioral benefits have been identified

[43,44], the psychosocial [45,46], and community benefits are the

cornerstone of DOC participation [47-49].

Events and meet-ups within DOCs are abundant, as are calls

to influence diabetes research and outcomes by initiating and codesigning

workshops and collaborative events like those hosted by

diabetes community organizations, Diabetes Mine, The Diabetes

Empowerment Summit, Diabetes Patient Advocacy Coalition

(DPAC), Diabetes Social Media Advocacy (DSMA), We Are Diabetes,

The College Diabetes Network, Diabetes Sisters, and more.

DOC users have also actively advocated against research

methodologies that focus exclusively on summative metabolic measurements pre-and post- intervention research. The hemoglobin

A1C is a blood test that measures the concentration of glycated

hemoglobin in the blood, representative of an individual’s 3-month

average blood glucose level. A1C is the most commonly used

clinical measure of glucose and is often used in the context of how

well someone is managing their diabetes in research. In response,

members across DOCs initiated a conference called “Beyond A1C”

bringing together stakeholders, including researchers and professional

organizations, to generate research ideas for measuring change

beyond A1C [50]. Within diabetes online communities (DOCs), a

user-generated term that encompasses people affected by diabetes

who engage in online activities to share experiences and support in

siloed or networked platforms [44], mobilization looks like social

media-based social movements through hash tags, the formation of

grassroots organizations (like Insulin4All), and public outcries in

response to stigmatizing media portrayals of diabetes. While clinical

and behavioral benefits have been identified [45,46], the psychosocial

[47,48], and community benefits are the cornerstones of DOC

participation [49-51].

Events and meet ups within DOCs are abundant, as are calls

to influence diabetes research and outcomes by initiating and codesigning

workshops and collaborative events like those hosted by

diabetes community organizations, Diabetes Mine, The Diabetes

Empowerment Summit, Diabetes Patient Advocacy Coalition

(DPAC), Diabetes Social Media Advocacy (DSMA), We Are Diabetes,

The College Diabetes Network, Diabetes Sisters, and more.

DOC users have also actively advocated against research

methodologies which focus exclusively on summative metabolic

measurements pre- and post- intervention research. The hemoglobin

A1C is a blood test which measures the concentration of glycated

hemoglobin in the blood, representative of an individual’s 3-month

average blood glucose level. A1C is the most commonly used clinical

measure of glucose and is often used in the context of how well someone

is managing their diabetes in research. In response, members across

DOCs initiated a conference called “Beyond A1C” bringing together

stakeholders, including researchers and professional organizations, to

generate research ideas for measuring change beyond A1C [52]. This

example demonstrates that diabetes online communities are actively

interested and involved in ensuring research methods make sense to

their lived experience, in itself an act of social empowerment.

Patients with diabetes who post diabetes-related content online

are actively engaging in self-empowerment by inserting their

argument into the research process and agenda, making the need

for a measure of social validity paramount. When measuring social

validity, researchers ask what is the social importance and community

acceptability of this study and the resulting findings [51]?[53]?

Including a measure of social validity would add to the knowledge

produced by the field and allow findings to be translated into the realworld

more seamlessly. However, this is not enough. The historical

movement away from reliance on metabolic outcomes and toward

psychosocial ones in diabetes is an indication that making a more

drastic shift is a possibility [38,40].

Methodological Gaps:

To quell the over-reliance of individually-based measures of

empowerment predominantly used in the diabetes space, more participatory frameworks are needed. When methods incorporate

participatory elements, the scope and concepts of what empowerment

means to communities will shift. It will become more possible for

research to build capacity within communities by recognizing the

potential importance of identification with the group as a form of

stigma management. Rather than seeing diabetes empowerment as a

form of self-efficacy to be gained by individuals, it can be translated

more into a process of creating or shifting power toward the diabetes

community as a whole. Some studies have done this by inviting

influencers of varying levels in social media spaces relevant to their

study populations to engage with the research [52]. One recent study

argues that beyond increasing the social validity of a study, engaging

with influencers through participatory design facilitates the flow of

information about the study and its subsequent findings [53,54].

One recent study argues that beyond increasing the social validity

of a study, engaging with influencers through participatory design

facilitates the flow of information about the study and its subsequent

findings [55]. What’s more, participatory frameworks are also often

paired with social change.The spirit of participatory action research is based on the concept

of participation and change theorized by Paulo Freire [54,56].

According to Freire, change relies on the participation, knowledge,

and buy-in of local community members who ought to be “partners

in the processes of knowledge creation and social change” [55,57]. Not

only are community members included as partners in the research

process using this framework, they also may more directly benefit.

Participatory action research has been regaled as a framework

which “may also yield research that is more socially relevant, valid,

and accessible to people with disabilities and communities alike;

qualities which may result in more actions to improve participation

opportunities and decrease disparities” [56,58].

There are examples beyond diabetes literature which embrace the

concept of empowerment as a process of creating or shifting power in

the health fields. One Australia-based study which used a participatory

design, brought together individuals from patient, advocacy, industry,

tech, research, and academic stakeholder groups to ask “What is

currently working and not working in digital health in Australia?”

and “Where should digital health go in the future?” [57,59]. By virtue

of its design, this study actively engages patients in empowerment

principles by giving them a seat at the table - something we need to

see more of as we reimaging empowerment within diabetes research

and care [60,61].

Reimagining Empowerment in Diabetes

It is imperative we use strategies intended to mobilize the

community when selecting participatory action research methods,

rather than those which perpetuate stigmatizing representations of

a diabetic person as lazy or unwilling to self-care. We acknowledge

that diabetes advocates in online spaces are already actively calling

for a more nuanced construct of empowerment, one which implicates

social conditions and inequities they face in their daily lives. We call

researchers in the fields of health, healthcare, and health services

to move toward participatory study designs which consider and

acknowledge online diabetes advocates so that we may collectively

reimaging diabetes empowerment.