Journal of Andrology & Gynaecology

Download PDF

Research Article

*Address for Correspondence: Miguel Ãngel Motos-Guirao, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Granada, Spain, Tel: 0034958242867; E-mail: mamotos@ugr.es

Citation: Motos-Guirao MÃ, Moreno-Mayo C. Sexual health promotion using social networks in Spain. J Androl Gynaecol. 2013;1(1): 5.

Copyright © 2013 Motos-Guirao MÃ, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Andrology & Gynaecology | Volume: 1, Issue: 1

Submission: 31 July 2013 | Accepted: 11 September 2013 | Published: 13 September 2013

Keywords: Social networking sites; Health promotion; Sexual health

Abbreviations: SNS: Social Networking Site; STD: Sexually Transmitted Disease; WHO: World Health Organization; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Sexual health promotion using social networks in Spain

Miguel Ãngel Motos-Guirao1*and Cristóbal Moreno-Mayo2

- 1.Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Granada, Spain

- 2.Cultural Anthropology, University of Sevilla, Spain

*Address for Correspondence: Miguel Ãngel Motos-Guirao, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Granada, Spain, Tel: 0034958242867; E-mail: mamotos@ugr.es

Citation: Motos-Guirao MÃ, Moreno-Mayo C. Sexual health promotion using social networks in Spain. J Androl Gynaecol. 2013;1(1): 5.

Copyright © 2013 Motos-Guirao MÃ, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Andrology & Gynaecology | Volume: 1, Issue: 1

Submission: 31 July 2013 | Accepted: 11 September 2013 | Published: 13 September 2013

Abstract

Background: Sexual health promotion is an act of social responsibility that usually centres on delivering practical advice to the general public or to risk populations. The methods for transmitting these recommendations have begun to change over the past few years, with the rapid growth of so-called social networking sites. The objective of this study was to investigate the involvement of these social networks in the promotion of sexual health in Spain.Methods: We investigated sexual health promotion activities in the most widely used social networking sites in Spain: Facebook, Twitter, and Tuenti, using a set of key words and analyzing particular characteristics of the records retrieved, including the type of body responsible or owner, the objectives, the subject matter, and the target population.

Results: We selected 124 records obtained from Twitter (65), Facebook (57), and Tuenti (2). Most of the owners were from the private sector, generally non-institutionalized, and the most frequent objective was to prevent exposure to the human immunodeficiency virus. The general public was the target population for most activities, followed by specific risk groups and young people/adolescents.

Conclusions: These are the first data published on sexual health promotion through social networking sites in Spain. The almost nonexistent use of Tuenti by public institutions and other social network agencies and actors means that a large number of Spanish adolescents, the main users of this network, do not access the few programmed activities for sexual health promotion. It is essential to investigate how adolescents access these networks before designing future interventions.

Keywords: Social networking sites; Health promotion; Sexual health

Abbreviations: SNS: Social Networking Site; STD: Sexually Transmitted Disease; WHO: World Health Organization; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Introduction

Health promotion is the process of enabling people to increase their control over and improve their health [1]. This is not only an individual aspiration but also an essential social responsibility of public institutions. Health promotion activities usually centre on the delivery of practical health advice to the general public or risk populations and are carried out by different private bodies, professionals, and non-profit organizations, as well as by governmental agencies. Conventionally, these messages have generally been transmitted to the population through the mass media (radio, television, etc.), although the most effective method is undoubtedly through direct interaction with individuals (e.g., in the physician-patient relationship) [2]. However, the Internet has brought a new form of communication and culture that offers direct and simultaneous access not only to single individuals but also to potentially vast numbers of people through social networking sites (SNSs) [3]. These sites can facilitate bidirectional, interactive contact between the deliverer and receiver of messages, making them of special interest for health interventions [4].It is estimated that 67.6% of the Spanish population use the Internet, compared with 77.9% in the USA and 82% in UK [5]. The age of Internet users in Spain ranges widely from 12 through 85 yrs, as in other developed countries, [6] while it is especially well established among adolescents and young adults, being used by 97.2% of the 16- 24 yr age group and 91.8% of the 25-34 yr age group [7]. A study of 811 Spanish adolescents (mean age of 17 yrs) found that 88% used the Internet and 57.5% employed it to access health-related data [8]. The most frequently used social networks in Spain are Facebook, Twitter and Tuenti [9] .Other well-known platforms, such as MySpace, are less well represented. The most recent estimations of the numbers of users are 17 million for Facebook and 5.7 million for Twitter (December 2012) [10]. The least known of these networks is Tuenti, a popular Spanish SNS [11] with more than 14 million users (September 2013) [12] aged between 18 and 30 yrs. Tuenti is the favorite network of 41% of Spanish adolescents aged between 14 and 17 yrs, and is especially popular with under-15-yr-olds [9], i.e., a highly relevant population for early sexual health promotion [5,6,9]. Its users have a younger age profile in comparison to Facebook (75% of users between 18 and 44 yrs, with only 1.08% of users under 15 yrs old) [13] and Twitter (predominantly 35 to 44 yr olds, with only 0.50% of users under 20 yrs old) [14]. Young people are especially vulnerable to sexual health problems [15,16] given that almost 35% of new cases of sexually transmitted disease (STD/AIDS) are reported in the 15-24 yr age group [17,18] and even more in other countries, as in the U.S. where these numbers reach almost 50% [19].

This new cultural world of human relations and intercommunications gives health promotion added relevance [20] when set in the context of social networking sites and this combination may be of special value in the sexual health field. Although studies have been published on the utilization of the new digital media [21,22] and in particular SNSs [23-25] for sexual health promotion, various important factors require further investigation, including the method by which information is accessed, its content and suitability, identification of the target population, the institutional use of this resource, and the keys to its successful implementation, among others.

The objective of this study was to analyze the use of SNSs for sexual health promotion in Spain, studying their characteristics and suggesting areas for potential improvement.

Material and Methods

The study material comprised all detected records of SNS activity related to sexual health promotion in Spain. The World Health Organization (WHO) definition of sexual health was employed: “… a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality... not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity” [26]. This understanding of the term allows three main areas of sexual health to be defined: physical-psychological health, education, and sexual behaviour. Based on these considerations, we selected the following search terms: Sexual health, Sexual behaviour, Sexual education, Contraception, Condoms, STDs, HIV, and AIDS. Each of these terms was placed in the respective search engine (Facebook, Tuenti, and Twitter), selecting the first 100 records that met the inclusion criteria (see below).In order to enhance the comparability of our results, we generally followed the methodology clearly set out by Gold et al. [23], the first authors to address this issue. We focussed on SNSs in the present study. General or specific medical search engines or blogs were not included, and the scientific literature was not searched for information on this issue in Spain, due to the negative results of a previous review by our group (data not published).

The SNSs selected for study were the most frequently visited in Spain at the time of writing [9] , with Facebook in first place, as in the rest of the world [27], followed by Tuenti and Twitter. A preliminary search revealed no relevant SNS activity before 2008, which was therefore considered the baseline year for the search. The records retrieved by the search were reviewed by two operators (M.M.G. and C.M.M.), who applied the following inclusion criteria:

1. An activity was considered to be any sexual health promotion or information or discussion aimed at educating or raising awareness about sexual health and behaviors.

2. Content must be related to promotion in the key fields of health, education, or sexual behaviour between 2008 and 2013. Websites with content unrelated to the subject matter or lacking in seriousness, repeated sites, and those not showing the country of origin or located in Spanish-speaking countries other than Spain were all excluded.

3. Only Spanish-language websites were included.

The items analyzed for each activity record were: Social Networking Site (Facebook, Twitter or Tuenti ), Title of activity (name used for this activity in the SNS), Entity (public or private body), Owner/organization responsible (indicating whether the person/organization responsible for the activity is an individual or an institution or any other professional or commercial body, etc), City in which the activity is located, Starting date of the activity, Objectives (when expressly reported), Sexual Health Focus (within the fields of interest for sexual health), and Target population (general population or a specific social sector). All data were stored on a database using Microsoft Access 2007.

Results

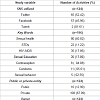

After applying the search criteria, a total of 1997 activity records were retrieved (785 from Twitter, 736 from Facebook, and 476 from Tuenti), of which 124 (6.21%) met the study inclusion criteria. Table 1 summarizes these findings.Social Networking SitesOut of the 124 records meeting study eligibility criteria, 65 (52.42%) were obtained from Twitter (total records retrieved=785), 57 (45.96%) from Facebook (total records =736), and only 2 (1.61%) from Tuenti (total=476).

Keywords

The search term yielding the largest number of records was sexual health (n=80, 40.81%), followed by STD, with or without HIV (n=57, 29.08%), sexual education (n=35, 17.85%), contraception, including condoms (n= 9.69%), and sexual behaviour (n=5, 2.55%).

Owner (Organization Responsible)

Among the owners or organisations responsible for the sites, 73.38% can be considered as "non-institutional" (associations, privatesector or individuals) and approximately 26.61% as “institutional†(governmental organization, NGO, or academic institution). Among the three platforms studied, Facebook and Twitter gave very similar results for the former groups (47 versus 44 records, respectively), but a larger number of more institutionalized activities (Government and Academic Institutions) were accessed via Facebook than via Twitter (11 vs. 4 records, respectively). Only two records meeting the inclusion criteria were retrieved from Tuenti (one institutional and the other individual).

City in which the activity is located

This information was usually absent (n=45; 36.29%), except when related to professional or institutional activities. Activity records were mainly grouped in the main Spanish cities of Madrid (n=31; 39.24%) and Barcelona (n=18; 22.78%), while the remainder were widely dispersed among urban centres (n=30; 37.97%).

Starting date of the activity

This information was not available for 68.55% (n=85) of the activities. No records were obtained before 2008. The year with the highest recorded activity was 2011.

Objectives

All of the recorded activities specified their objectives, but their systematic classification is complex. The objective was: the prevention of HIV via different exposure routes in 23.38% of records; general sexual health information in 19.35%; diagnostic and therapeutic sexological assessment of the general population in 15.32%; education in 12.09%; defence or awareness of sexual rights in 7.26%; commercial interests in 6.45%; promotion of contraceptive methods to preserve sexual health in 4.84%; institutional sexual health campaigns in 4.84%, and other objectives in 6.45%.

Sexual health focus

The records were grouped into five major areas: sexual health (n=124, 41.05%), sex education (n=71, 23.50%), STDs (with or without HIV) (n=45; 14.90%), sexual behavior (n=35; 11.58%), and contraception (n=27; 8.94%). The total (n=302) exceeds the number of records retrieved because the same activity can be grouped in more than one area.

Target population

Seven target populations were identified for the activities : general population (n=78; 62.90%); population with specific sexual health risks (lesbians, gays, transsexuals, bisexuals (LGTB groups) (n=9; 7.25%); HIV+ population (n=7; 5.64%); specifically male population (n=4; 3.22%); specifically female population (n=7; 5.64%); young population (young people and adolescents) (n=12; 9.67%); and others (n=7; 5.64%), including education professionals (n=1), healthcare professionals (n=2), sexology graduates (n=2) and journalists (n=2).

Discussion

In this study, the highest number of sexual health-related records was obtained via Twitter, followed by Facebook, whereas very few records meeting our inclusion criteria were obtained via Tuenti. This raises the question as to whether SNSs may not be the ideal medium for transmitting sexual health messages to adolescents and young parents, as suggested by some authors [28]. In a pilot study of older adolescents (18-19 yrs), Moreno et al. [29] proposed the use of Facebook profiles to identify sexually active adolescents who might benefit from specifically-designed educational messages [30]. Gold et al. [23] found that 29.8% of activities were aimed at young people, in comparison to only 9.67% in the present study, which may be attributable to the lack of activities available via Tuenti. The widespread use of the Internet and its related services by adolescents, including searches for health information, coincides with a special need for intervention in this age group to protect their sexual and reproductive health [31]. For this reason, it appears essential to maintain and develop the capability to generate and transmit sexual health information through social networks in order to encourage the access and participation of young people [25,32].The use of key words can condition search results, and we therefore used terms clearly related to sexual health promotion. Sexual Health was, unsurprisingly, the most frequent term, beingwidely used among the different population groups, as was also the case for the term Sexual Education. Highly specific but especially resonant terms such as condom, AIDS, or HIV were useful to identify appropriate records, whereas the term Sexual Behaviour proved less helpful in our specialized search.

Different criteria can be used to classify the organizations responsible for the activities of interest, although the identification of governmental associations is of particular interest. These were responsible for 6.45% of the activities in the present investigation, in comparison to 15.7% in the study by Gold et al. [23], reflecting an unacceptably low presence of governmental institutions. We included Internet activities not covered in the Gold study, such as professional and commercial websites. Professionals (psychologists, sexologists, and physicians) were considered in the present survey because of the important role they can play in sexual health promotion, using their professional prestige to give their content more credibility and increasing the capacity for interaction with the population of interest. We also included activities carried out by journalists (2 records), i.e., related to another form of educational health promotion. Although commercial records (essentially for on-line retailers) cannot be considered as sexual health promotion activities, they were included in this study. Because they should be taken into account in future research on their contribution to the development of adolescent sexual health, for example by encouraging the use of condoms.

The promotion of programs by non-governmental organizations and bodies was the most frequently recorded purpose of the activities; followed by the linking together of individuals with shared interests (e.g., groups for lesbians, gays, transvestites, bisexuals or HIV+ individuals). The proportion of institutional programs or campaigns was lower in our study (11.29%) than in the survey by Gold et al (28.7%) [23], which suggests a certain lack of development by Spanish institutions in this regard. The most extreme example of this neglect was provided by the Tuenti platform, from which only one institutional (local) record was obtained, underlining the severe under-utilization of this network, not only by institutions, who fail to include it in prevention or information campaigns, but also by professionals, preventive associations, NGOs, and other agencies.

The grouping of subject matters in our study differs from that used by Gold et al. [23] with the addition of sexual education, sexual behaviour, and contraception (in general and condoms). As expected, the most frequent subject matter in our study was sexual health (40.59%), followed by HIV+/STDs (33.06%), and sexual education (15.34%), which was not explicitly described by Gold et al. [23]. We were also interested in examining activities centred on sexual behaviour, a more sensitive and conflictive subject. We also included activities on contraception, to which 8.91% of the records were related. We did not address the issue of the specific contents transmitted and the means to be adopted for this purpose. Byron [33] warned about the risk to young people of sharing sexual information through SNSs and proposed that sexual health promotion messages should be adapted to these new instruments and adopt a humorous approach.

Besides the general population, we studied two populations facing specific sexual health risks: LGTB groups and HIV+ individuals. Although the frequency of activities was not high for these two populations, which together represented only 12.89% of the records, they are of interest because specific health promotion contents are required to meet their needs, largely related to preventive measures in the former and both preventive and therapeutic measures in the latter. Magee [34] investigated on-line access to information on sexual health by young LGTB groups and highlighted that 63% of participants in the study wanted (more frequently with younger age) the inclusion of links to SNSs from sexual health information websites in order to create profiles, exchange experiences, and chat with other young people in their situation. These findings confirm previous proposals by Bennett and Glasgow [35] on the capacity of these tools to engage the LGTB population and the need to improve the quality of the information received. There has also been debate on the benefits for the HIV+ population and STD carriers of SNS interventions, i.e., whether they can generate behaviour changes helpful for disease prevention and sexual health improvement. A recent study by Bull [36] found that this type of intervention could prevent a reduction in the use of condoms by young people at high risk, at least over the short term. Finally, it is important to acknowledge the need to design specific interventions for the different population groups, whether high-risk or not, by sex and age. In the present study, the target population could be identified for all activities recorded, whereas this did not prove possible in almost half of the records retrieved in the study by Gold et al. [15].

Conclusions

The use of SNSs for sexual health promotion is a new cultural paradigm that entails a change in the relationships among all participants in these networks, including physicians, patients, institutions, and associations, among others. Four main questions need to be asked in the context of sexual health promotion: 1) what contents should be generated for each population sector according to age, sex, health status, and interests? 2) How do these sectors interact with the contents of their respective activities? 3) Can SNS-based interventions contribute to improving the sexual psychophysical state of the target population? And 4) what are the instruments required characterizing these activities? Various researchers have explored these methodological aspects [23,25,29,32] and have begun to explore the results of some of these interventions [4,22,24,35,36]. However, the first two questions remain unanswered. The present investigation depicts the situation of SNS use in Spain, describing the different target groups and the distribution and diversity of the contents and objectives. We highlight the inadequate participation of governmental institutions in SNS activity. The almost total absence of activities in the Tuenti network is striking and implies that many Spanish adolescents, the main users of this network, do not access the few activities provided by public institutions and different associations. In-depth study of the sites actually used in the country of interest, including local platforms, is required before the design or development of intervention activities in the field of sexual health promotion, especially those targeting adolescents.References

- World Health Organization (1986) Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. First International Conference on Health Promotion.

- Redmond N, Baer HJ, Clark CR, Lipsitz S, Hicks LS (2010) Sources of health information related to preventive health behaviors in a national study. Am J Prev Med 38: 620-627.

- Boyd DN, Ellison N B (2007) Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13: 210-230.

- Muñoz RF (2010) Using Evidence-Based Internet Interventions to Reduce Health Disparities Worldwide. J Med Internet Res 12: e60.

- Tatum SL (2011) Internet Report on Spain and the world. Current status of social networks in Spain. (Article in Spanish).

- Instituto Nacional de EstadÃstica (2013) Survey on the Equipment and Use of ICT.

- The World Bank (2013) Internet users (per 100 people).

- Jiménez-Pernett J, Olry de Labry-Lima A, Bermúdez-Tamayo C , Jose Francisco GarcÃa-Gutiérrez, Maria del Carmen Salcedo-Sánchez (2010) Use of the internet as a source of health information by Spanish adolescents. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 10: 6.

- Interactive Advertising Bureau. Spain Research (2013) IV Annual Study Social Networks.

- ComScore: Analytics for a Digital World (2013) Spain Digital Future in Focus.

- Social Network Tuenti (2013).

- Tuenti Corporate (2013) We’re 14 million

- Owloo (2013) Demographic on Facebook.

- Adigital (2012) Study of the use of twitter in Spain.

- Bearinger LH, Sieving RE, Ferguson J, Sharma V (2007) Global perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents: patterns, prevention, and potential. Lancet 369: 1220-1231.

- Secor-Turner M, Kugler K, Bearinger LH, Sieving R (2009) A global perspective of adolescent sexual and reproductive health: Context matters. Adolesc Med State Art Rev 20: 1005-1025.

- Ministerio de Sanidad de España. Instituto Carlos III (2011) Epidemiological surveillance of sexually transmitted infections. Article in Spanish.

- Instituto Nacional de EstadÃstica (2012) Surveillance of HIV/AIDS in Spain. Article in Spanish.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011) Sexuality transmitted diseases surveillances.

- SedisasigloXXI (2012) Provision of internet and social networks to promote health.

- Allison S,. Bauermeister JA, Bull S, Lightfoot M, Mustanski B, Shegog R, et al. (2012) The Intersection of Youth, Technology, and New Media with Sexual Health: Moving the Research Agenda Forward. J Adolesc Health 51: 207–212.

- Kylene Guse , Deb Levine , Summer Martins, Andrea Lira , Gaarde J, et al. (2012) Interventions Using New Digital Media to Improve Adolescent Sexual Health: A Systematic Review. J Adolesc Health 5: 535-543.

- Gold J, Pedrana AE, Sacks-Davis R, Hellard ME, Chang S, et al. (2011) A systematic examination of the use of online social networking sites for sexual health promotion. BMC Public Health 11: 583.

- Gold J, Pedrana AE, Stoove MA, Chang S, Howard S, et al. (2012) Developing health promotion interventions on social networking sites: recommendations from The FaceSpace Project. J Med Internet Res 14: e30.

- Nguyen P, Gold J, Pedrana A, Chang S, Howard S, et al. (2013) Sexual Health Promotion on Social Networking Sites: A Process Evaluation of the FaceSpace Project. J Adolesc Health. 53: 98-104.

- World Health Organization (2013) Sexual and reproductive health. Working definitions. Sexual health.

- Cosenza V (2013) World map of social networks.

- Divecha Z, Divney A, Ickovics J, Kershaw T (2012) Tweeting About Testing: Do Low-Income, Parenting Adolescents and Young Adults Use New Media Technologies to Communicate About Sexual Health. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 4: 176–183.

- Moreno MA, Brockman LN, Wasserheit JN, Christakis DA (2012) A pilot evaluation of older adolescents’ Sexual reference displays on Facebook. J sex Res 49(4) 390-399.

- Gray NJ, Klein JD (2006) Adolescents and the internet: Health and sexuality information. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 18: 519-524.

- Bearinger LH, Sieving RE, Ferguson J, Sharma V (2007) Global perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents: patterns, prevention, and potential. Lancet 369: 1220–1231.

- Yager AM, O’Keefe C (2012) Adolescent Use of Social Networking to Gain Sexual Health Information. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners 8: 294-298.

- Byron P, Albury K, Evers C (2013) “It would be weird to have that on Facebookâ€: young people’s use of social media and the risk of sharing sexual health information. Reprod Health Matters 21: 35-44.

- Magee JC, Bigelow L, DeHaan S, Mustanski BS (2012) Sexual health information seeking online: a mixed-methods study among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender young people. Health Educ Behav 39: 276–289.

- Bennett, GG, Glasgow, RE (2009) The delivery of public health interventions via the Internet: Actualizing their potential. Annu Rev Public Health 30: 273-292.

- Bull SS, Levine DK, Black SR, Schmiege SJ, Santelli J (2012) Social media-delivered sexual health intervention: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 43: 467-474.