Journal of Andrology & Gynaecology

Download PDF

Case Report

Giant Ovarian Mass: About an Uncommon Case Report

Slaoui A1,2*, Mahtate M1, Slaoui A2, Koutani A2, Iben Atyya A2, Zeraidi N1, Lakhdar A1, Kharbach A2 and Baydada A1

1Department of Gynaecology-Obstetrics & Endoscopy, Maternity

Souissi, University Hospital Center IBN SINA, University Mohammed

V, Rabat, Morocco

2Department of Gynaecology-Obstetrics & Endocrinology, Maternity

Souissi, University Hospital Center IBN SINA, University Mohammed

V, Rabat, Morocco

3Urology Department, Avicenne Hospital, University Hospital

Center IBN SINA, University Mohammed V, Morocco

*Address for Correspondence: Slaoui A, Department of Gynaecology-Obstetrics & Endoscopy, Maternity

Souissi, University Hospital Center IBN SINA, University Mohammed V,

Rabat, Morocco; E-mail: azizslaoui27@gmail.com

Submission: 10 October, 2022

Accepted: 18 November, 2022

Published: 22 November, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Slaoui A, et al. This is an open access article

distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background: Ovarian giant masses remain today an uncommon

clinical presentation thanks to their early incidental radiological

discovery. Their symptomatic presentation is usually characterized

by abdominopelvic pain and a feeling of heaviness. The most

important management is the removal of the tumor in order to allow

the anatomopathological study which is the only way to confirm or

deny the malignancy. We hereby present an atypical case due to its

occurrence in a young 48-year-old female patient, the considerable

size of the tumor, its non-specific clinical and radiological presentation

making the diagnosis difficult.

Case Presentation: This was the case of a 48-year-old woman with

no particular antecedents, gravida 5 para 4 with four vaginal deliveries

resulting in the birth of four healthy children and one miscarriage. She

came to our department for management of a large abdominopelvic

mass of more than 30 cm that was bulging out all abdominal organs.

She had an MRI that strongly suspected ovarian origin and ROMA score

that came back negative for malignancy. A left oophorectomy was

followed by abdominal plasty. Anatomopathological study confirmed

a serous cystadenoma with no sign of malignancy. The patient was

discharged at D4 postoperatively. The follow-up was uneventful.

Conclusion: Giant ovarian masses, although uncommon, raise

a double difficulty for the clinician. On the one hand, the diagnosis,

although largely guided by MRI, can only be confirmed during

surgery. On the other hand, it represents a surgical challenge

whether by laparotomy or by laparoscopy. In addition, the ROMA

score based on the dosage of tumor markers CA125 and HE4 allows

malignant tumors to be screened, but confirmation is only provided by

anatomopathological study, hence the importance of not rupturing

the cyst during its extraction.

Abbreviations

BMI: Body Mass Index; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging;

ROMA: Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm

Introduction

Ovarian giant masses remain today an uncommon clinical

presentation thanks to their early incidental radiological discovery.

Their management depends on the size of the tumor, the age of the

patient and the histological type [1]. Frequency of malignancy is only

37-66% in perimenopausal women and 18-86% in postmenopausal

women [2,3]. We hereby present an atypical case due to its occurrence

in a young 48-year-old female patient, the considerable size of the

tumor, its non-specific clinical and radiological presentation making

the diagnosis difficult. We then confront this case with the data of the

literature.

Case presentation

We hereby present the case of a young 48-year-oldfemale patient,

gravida 5 para 4 with four live children delivered vaginally and

one miscarriage, who came to our structure for management of an abdominal mass evolving for about 8 years. The initial erroneous

diagnosis of chronic ascites had been made and several evacuation

punctures had been performed. The patient complained of chronic

pelvic pain, complicated by digestive disorders with alternating

diarrhea, constipation and vomiting. The examination on admission

revealed an apyretic and stable hemodynamic state, a much distended

abdomen, with hyper lordosis making any movement of the patient

difficult. The patient weighed 90 kg for a height of 1.64 m with

a BMI of 33.5, the xypho-pubic distance was 60 cm, the umbilical

circumference was 100 cm. The vulva-perineal inspection was

without particularity and the speculum revealed a healthy cervix

without bleeding or leucorrhea, the vaginal examination coupled

with the abdominal palpation showed the presence of an enormous

mobile abdomino-pelvic mass which could not be separated from the

uterus. On rectal examination, a prolapsed liquid mass was perceived

in the Douglas pouch, the recto-vaginal septum and the parameters

were without particularity.

Ultrasound revealed a large abdomino-pelvic mass of difficult

exploration containing diffuse particles with localized small thickened

partitions and no visible intestinal loop. The liver, spleen and kidneys

were normal. Abdomino-pelvic MRI showed a huge cystic mass with

clear and regular contours and vegetation on the right anteroinferior

wall. It measured 35.7 x 22.4x12 cm without peritoneal effusion or

liver lesion. Biologically, the tumor markers including CA125 and

HE4 were normal. ROMA score was negative.

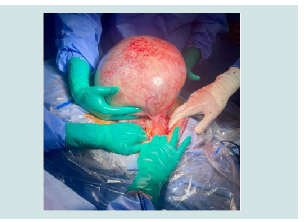

Xyphopubic median laparotomy confirmed the diagnosis of a

large cyst of the left ovary very adherent to the anterior abdominal

wall and the intestinal loops (Figure 1). The uterus and right adnexa

were of normal size and morphology. A left oophorectomy was

performed after extensive adhesiolysis. Anatomopathological study

showed macroscopically a cystic mass measuring 32x23x12 cm with a thin wall and clear liquid content and microscopically a cystic cavity

lined by a cubic epithelium with a band of fibrous connective tissue; in

some places there were pieces of normal ovarian parenchyma in favor

of a serous cystadenoma and no histological evidence of malignancy.

The epiploic and peritoneal biopsies and the peritoneal cytology were

free of any tumor infiltration.

Surgery included an abdominal plasty, preserving the umbilicus

with multiple suction drains. The patient’s weight went from 90 kg

to 76 kg, allowing her BMI to go from 33.5 to 28.3, her umbilical

perimeter from 100 cm to 68 cm and her xyphopubic distance from

60 cm to 29 cm. The postoperative course was simple with resumption

of transit on day 2 postoperatively. The patient was discharged home

at 4 days postoperatively. The follow-up was uneventful.

Discussion

Giant ovarian cysts are relatively uncommon; between 1947 and

1988, only 25 cases were described in the literature [4]. The largest

ovarian cyst described in the literature was reported in Texas in 1905

and was reported to have weighed 169 kg [5]. The diagnosis of these

giant ovarian cysts is usually easy in the presence of disproportionate

abdominal distension with depletion of the umbilicus and alteration

of the general condition. Ignorance, negligence and sometimes fear of

hospitals explain the delay in consultation in low-and middle-income

countries. A giant cyst of the ovary may simulate severe obesity or

abundant ascites [4,6].

Exploration of giant ovarian cysts relies essentially on ultrasound

and MRI. The last allows a more precise diagnosis and a better

understanding of the tumor’s relationship with other nearby organs

[4,7-10]. Surgical management of giant ovarian cysts requires perfect

collaboration between surgeons and anesthetists. The surgical

procedure can be fraught with complications such as hypovolemic

shock on removal of the tumor, intraoperative hemorrhage,

atelectasis, pulmonary edema and postoperative ileus [5,6]. All

of these conditions can be prevented by careful vascular filling,

positioning the patient in the left lateral decubitus position prior

to tumor removal, and also by proper colonic preparation of these

patients [5,6]. The wide approach by xypho-pubic incision allows a

good exposure with progressive and careful dissection of the cyst.

Given the significant stretching of the anterior abdominal wall,

abdominoplasty by longitudinal or transverse elliptical excision of the

excess skin is necessary for aesthetic reasons and above all to promote

respiratory mechanics [7,8].

Since the advent of laparoscopy and more particularly at the

beginning of the 2000s, several authors have managed giant ovarian

cysts laparoscopically, but as intra-abdominal rupture can be

dramatic for the patient especially in case of malignancy [11,12], we

have chosen classical management.

The specificity of this case is the presence of a giant mass in a

perimenopausal patient with a slow evolution of the symptomatology.

The frequency of malignancy is 37 to 66% and the size of the tumor

points to a malignant pathology [2,3]. Serous cystadenomas produce

non-specific symptoms. The most common symptoms include a

feeling of pressure in the lower abdomen and symptoms of the

gastrointestinal and urinary systems. Acute pain may also occur

with adnexal torsion or cyst rupture [13]. Serous tumors develop by

invagination of the surface epithelium of the ovary and secrete serous

fluid. Generally benign, 5-10% has borderline malignant potential

and 20-25% is malignant [14].

Measurement of the tumor marker CA125 may be helpful [15].

Many benign conditions such as fibroids, pregnancy, endometriosis,

and pelvic inflammatory disease can cause elevated CA125 levels [16].

More recently, the biomarker HE4 has been evaluated and appears

to be as sensitive as CA125 and better predictive of recurrence

than CA125 [17]. The ROMA score with both markers provides

greater sensitivity and specificity [18]. In our patient the score was

negative which is in correlation with our anatomopathological

study which did not find any sign of malignancy. Indeed, it is only

the anatomopathological examination that distinguishes between

benign, borderline and malignant serous tumors.

Conclusion

Giant ovarian masses, although uncommon, raise a double

difficulty for the clinician. On the one hand, the diagnosis, although

largely guided by MRI, can only be confirmed during surgery. On the

other hand, it represents a surgical challenge whether by laparotomy

or by laparoscopy. In addition, the ROMA score based on the dosage

of tumor markers CA125 and HE4 allows malignant tumors to be

screened, but confirmation is only provided by anatomopathological

study, hence the importance of not rupturing the cyst during its

extraction.

References

13. Muronda M, Russell P (2018) Combined ovarian serous cystadenoma and thecoma. Pathology 50: 367-369.