Journal of Analytical & Molecular Techniques

Download PDF

Research Article

Parboiled Preservation of Odonata Nymphs for DNA Related Research

Sutherland LN1*, Fomekong-Lontchi J1,5*, Lupiyaningdyah P1,4, Tennessen KJ3, Carter P1 and Bybee SM1,2

1Department of Biology, Brigham Young University, 4102 LSB,

Provo, UT 84602, USA

2Bean Life Science Museum, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA

3Florida State Collection of Arthropods, Gainesville, Florida, USA

4Research Center for Biosystematics and Evolution, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Cibinong, West Java, Indonesia

5Institute of Medical Research and Medicinal Plants Studies (IMPM), Centre of Medical Research, P.O Box: 6163 Yaoundé, Cameroon

2Bean Life Science Museum, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA

3Florida State Collection of Arthropods, Gainesville, Florida, USA

4Research Center for Biosystematics and Evolution, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Cibinong, West Java, Indonesia

5Institute of Medical Research and Medicinal Plants Studies (IMPM), Centre of Medical Research, P.O Box: 6163 Yaoundé, Cameroon

*Address for Correspondence:Sutherland LN, Department of Biology, Brigham Young University,

4102 LSB, Provo, UT 84602, USA E-mail Id: lns25@byu.edu

Submission:09 December, 2024

Accepted:15 January, 2025

Published:20 January, 2025

Copyright: ©2025 Sutherland LN, et al. This is an open access

article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License,

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords:Dragonfly; Damselfly; Nymphs; DNA; Parboil

Abstract

Odonate nymph preservation is less standardized and more prone to

long-term preservation issues than adults.Two preemptive measures that

can be taken to help prevent the high level of decay often seen in older

nymph specimens are 1. Ethanol injection 2. Parboiling. Parboiling offers

the long-term advantage of better retaining the morphology, which is a great

advantage for future taxonomic projects. Here we found that parboiling is as

good for preserving DNA as ethanol injection.

Introduction

Natural history collections have been the backbone of systematic

and taxonomic research by housing well-preserved specimens that

offer repeatability and comparability in phenotypic analyses [1]. The

importance of natural history collections has received a growing

amount of attention [1-6] in the face of the biodiversity crisis and

continual underfunding. This resurgence in museum interest is

due in part to the increase in digitization efforts and advances in

technology that allows for the sharing of data at a global scale [7].

Museum specimens have long been used in large-scale evolutionary,

biodiversity, and ecological research, but the increase in publicly

available data has created opportunities for broader and more

collaborative research to take place [8]. Recently, there have been calls

to address issues (e.g., lack of administrative support, understaffing,

declines in specimens being deposited, specimen degradation) in

natural history collections to set them up for success in this next

phase of broader museum-based research [4,1]. One way to ensure

museum-based research will continue long into the future is to

consistently use best practices for long-term preservation and storage

methods, which will vary by group.

In general, insect collections are extensive, and odonates

(dragonflies and damselflies) collections are no exception. For

instance, a recent survey was conducted at 13 institutions that possess

at least 100 odonate-type specimens [9]. Among these are the Florida

State Collection of Arthropods (~1.1 million specimens), the Naturalis

Biodiversity Center (~200,000 specimens), and the Natural History

Museum at London (~110,000 specimens) demonstrating the sheer

size of odonate collections. Due to the scale of these collections and

limited expertise, there is often a backlog of processing and taxonomic

work where specimens potentially sit for years, so morphological and

genetic preservation is critical.

Odonata is a medium-sized hemimetabolous order that has

become highly studied and collected due to brilliant coloration,

charismatic behavior, and aquatic lifestyle. Historically, odonates

have been used as biological indicators of freshwater health [10-13]

and often collected as nymphs in large biodiversity projects and

deposited in museums for later identification. While adult taxonomy

is relatively well known, nymph taxonomy is greatly understudied,

with less than half of the recognized species having a documented

nymph, as more effort has traditionally been spent on rearing nymphs

to adults for identification [14]. While nymph taxonomy is greatly

lagging behind adult taxonomy, there has been an effort to close this

gap in recent decades. For example, the majority of species in Ischnura

are known compared to approximately 20% of Telebasis. Historically,

more work has been done on Anisoptera than Zygoptera, but early

nymph descriptions are often brief, lacking detailed illustrations, and

in need of reexamination, highlighting the need for well-preserved

nymph specimens in collections.

Adult odonates preservation has become standardized with

three methods. First, specimens are air-dried and stored in glassine

envelopes without any additional preservation measures, which

allows for the coloration to fade over time and provides inconsistent

results in genetic studies. Second, the specimens are adjusted (i.e.,

wings folded above the abdomen and legs stretched) and then soaked

in acetone for 12-14 hours after which they are dried and again stored

in glassine envelopes. Acetone is excellent for preserving coloration

which is an important character in adult odonate taxonomy and

evolutionary research. Lastly, adults are stored in 70%-95% ethanol.

Ethanol preservation is ideal for genetic studies but can cause

significant color fading if left in the light.

Nymph preservation is less standardized and more prone to longterm

preservation issues than adults. Nymphs generally are preserved

straight into 70-95% ethanol, but ethanol does not readily penetrate

the cuticle, and often results in the specimen decaying to varying

degrees [15,16]. Perforations are often made in the abdomen of large

specimens in an attempt to help the ethanol penetrate the specimen,

but this compromises morphological features that could be needed for

identification in the future. Also, neglecting to refresh the ethanol will

affect the long-term preservation of DNA. There are two preemptive

measures (ethanol injection and parboiling) that can be taken to help

prevent this high level of decay. Ethanol injection, a fairly common

preemptive measure, is when 95% ethanol is directly injected into the

specimens upon capture. Parboiling, a technique not often utilized in

odonates, consists of dispatching the specimen by placing it briefly in

boiling water [14]. Boiling insects fixes the proteins in the body and

prevents them from decaying over time [17].

Parboiling offers the long-term advantage of retaining the

morphological dimensions and patterns of the specimens, closer to

what they are under living conditions, which is a great advantage

for future taxonomic projects. The benefits of parboiling have been

demonstrated in other groups. For example, caterpillars, if not boiled,

will decompose and turn black [18,19]. Parboiling has additionally

been shown to be effective in forensic research when estimating postmortem

intervals as it keeps the size, coloration, and internal organs

of larvae closer to their natural states [20]. Although parboiling

provides long-term stability of morphological features in odonate

nymphs (KTJ, personal comment) it is still unclear how efficiently it

preserves genetic material. Here we aim to

1. Test if there is a difference between the DNA quantity

captured based on the initial preservation method (parboiled

vs. ethanol injected) in odonate nymphs and

2. Test if there is a difference in DNA degradation (fragment

length) between the initial preservation methods.

Materials and Methods

Specimen preservation and sampling:

Odonate nymphs were collected from multiple locations in

Wisconsin, and one location in New York. Freshly collected nymphs

were initially preserved in one of two ways: ethanol injection or

parboiling. Parboiling consisted of submerging the nymph in boiling

water for 30–60 seconds, depending on size. All specimens, regardless

of initial preservation method, were stored in 80% ethanol in a -20°Cfreezer. Thirty-eight specimens were selected for extraction which

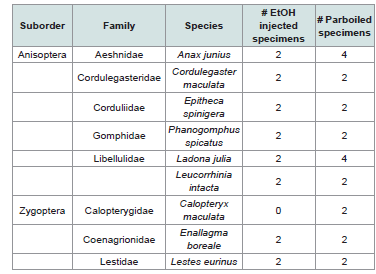

represent nine species (6 Anisoptera, 3 Zygoptera) [Table 1].

DNA Extraction and Quantification:

For each species at least four specimens (two per initial

preservation method) were extracted, except for Calopteryx maculata

where no ethanol injected specimen was available [Table 1]. Each

specimen was extracted three times (pro-, meso- and metathoracic

legs) and the variation in concentration between species is depicted

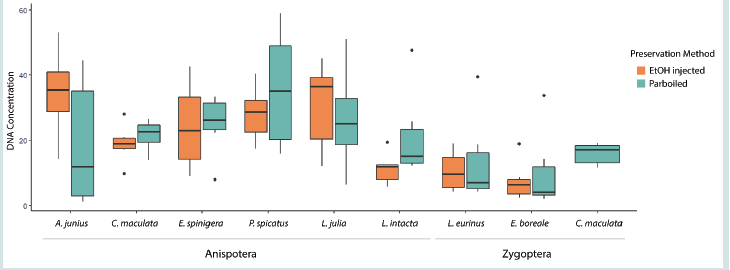

(Figure 1). DNA extractions were performed using a Qiagen DNeasy

Blood & Tissue kit (Valenica, CA) following manufacturer protocols,

with two exceptions. The sample was incubated at 56°C for 72 hours

during tissue lysis and the final elution volume was changed to 25 μL

which resulted in a final volume of ~45 μL. A Qubit 4 fluorometer

was used to quantify the DNA concentration with the dsDNA High

sensitivity procedure.DNA Degradation:

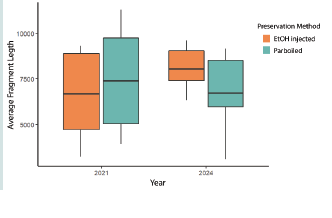

To test for DNA degradation over time, specimens were reextracted

in 2024, three years after the initial extractions. In total

32 extractions were selected, 16 extractions (8 ethanol injected, 8

parboiled) from 2021 and 16 new extractions performed in 2024.

All but Lestes eurinus was re-extracted. As an estimate for DNA

degradation, a fragment analysis was performed using the Agilent

Genomic 55 kb BAC Kit Quick Guide for Femto Pulse Systems at the

BYU DNA Sequencing Center. Two parboiled extractions from 2024

(Calopteryx maculata and Leucorrhinia intacta) were removed from

further analysis as no fragment length was recovered.Statistical analysis:

To test for a difference in DNA concentration between the initial

preservation methods (ethanol injected and parboiled), a Mann-

Whitney U Test was run in Rstudio v. 4.4.1 using the wilcox.test

function in the dplyr package [21]. To test the stability of the genetic

material by initial preservation two Mann-Whitney U Tests were run,

one for each year (2021 and 2024).Results

While there is variation in the DNA concentration between

species [Figure 1], in general, the average DNA concentration (ng/μl)

was higher for species in Anisoptera (24.3) than Zygoptera (11.5). The

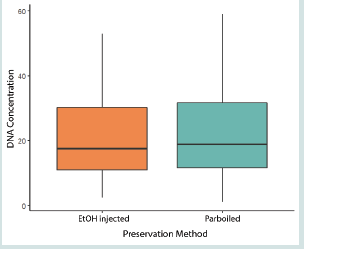

average DNA concentration was 20.7 and 21.0 for ethanol injected

and parboiled specimens, respectively. The results of the Mann-

Whitney U Test showed that there is no significant difference (W

= 1590.5, p-value = 0.97) in DNA concentration recovered between

parboiled and ethanol-injected specimens [Figure 2].

For the extractions completed in 2021, the average fragment

length (bp) for ethanol injected specimens was 6,620 compared to

7,529 for the parboiled specimens. However, based on the results of

the Mann-Whitney U Test, there is no difference (W = 25, p-value =

0.49) in fragment length between the methods. For the extractions

completed in 2024, the average fragment length (bp) for ethanol

injected specimens was 8,113 compared to 6,754 for the parboiled

specimens. The results of the Mann-Whitney U Test for the 2024

extractions indicate that there is no difference (W = 33, p-value =

0.27) in fragment length between the methods [Figure 3].

Discussion

The results above demonstrate that there is no difference in DNA

quantity or quality between initial preservation methods (ethanol

injected and parboiling) over time. Therefore, to better preserve

nymph morphology, parboiling should be the standard practice.

Parboiling has the benefit of slowing down degradation caused by

enzymes, which helps preserve the morphological integrity of the

nymph [20]. For long-term storage, nymphs should be kept in either

high concentration ethanol (95-100) or -80°C freezers with a lower

ethanol concentration (70-100). While both have issues, such as

brittle specimens leading to a high probability of breakage for high

concentration ethanol specimens, and DNA degradation due to the

rapid freezing and thawing when working with -80°C freezers, they

are still the current best practices [22,23].

Nymph taxonomy and identification are based almost solely on

the final instar. However, with the high level of adult sequences that

are publicly available, it is possible to associate unknown nymphs

at various stages with relative ease and accuracy. This approach

will allow researchers to get better insight into the different instars,

there by expanding our understanding of nymph development,

morphology, and taxonomy. Additionally, it will allow for increased

use of museum s pecimens, as more nymphs will be utilized which are

not at final instar. The benefits will be increased if parboiled specimens

are utilized, as a more detailed description can be provided at the end.

Relatively little is known about which morphological nymph

characters demonstrate phylogenetic synapomorphies across the

order, although some integrative studies have appeared [24-27].

Nymph characters have been found to help resolve generic limits

in the past [28-30]. Questions remain regarding whether certain

mouthparts (i.e.,premental and mandibular structure), thoracic

morphology, and lateral abdominal and anal gills show relationships

within or between groups [29,14]. Therefore, nymph preservation

is critical to all stages of systematic, phylogenetic, and evolutionary

research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the BYU undergraduates who helped with

DNA extractions and the BYU sequencing center for performing the

fragment analysis. We also thank Dr. Dennis Paulson for information

on the importance of insect collections for many fields of biology.