Journal of Addiction & Prevention

Download PDF

Review Article

‘I Think Smoking’s the Same, but the Toys Have Changed.’ Understanding Facilitators of E-Cigarette Use among Air Force Personnel

Little MA1*, Pebley K2, Porter K1, Talcott GW1,3 and Krukowski RA4

1University of Virginia, School of Medicine, Department of Public Health Sciences, 560 Ray C. Hunt Drive, Charlottesville, VA, USA 22903,

2University of Memphis, Department of Psychology, 400 Innovation Drive, Memphis, TN, USA, 38152

3Wilford Hall Ambulatory Surgical Center, 59 MDW/ 59 SGOWMP, 1100 Wilford Hall Loop, Bldg 4554, Joint Base Lackland AFB, TX, USA 78236

4Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, 66 North Pauline Street, Memphis, TN, USA 38163

*Address for Correspondence: Little MA, University of Virginia, School of Medicine, Department of Public

Health Sciences, 560 Ray C. Hunt Drive, Rm 2119 Charlottesville, VA, USA, 22903; E-mail: mal7uj@virginia.edu

Submission: July 24, 2020;

Accepted: August 28, 2020;

Published: August 31, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Little MA. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background: The military has stringent anti-tobacco regulations for new recruits. While most tobacco products have declined in recent

years, e-cigarette use has tripled among this population. However, little is known about the factors facilitating this inverse relationship.

Objectives: Examine the facilitators of e-cigarette use during a

high risk period following initial enlistment among young adults.

Methods: Focus groups were conducted with Airmen, Military

Training Leaders (MTLs) and Technical Training Instructors (TTIs) to

qualitatively explore unique characteristics of e-cigarettes leading to

use in Technical Training.

Results: The most commonly used tobacco product across

participants was cigarettes (42.7%), followed by e-cigarettes (28.0%)

and smokeless tobacco (22.6%). Almost a third (28.7%) of participants

reported using more than one tobacco product. E-cigarette use was

much more common among Airmen (76.1%), compared to MTLs

(10.9%) and TTIs (13.0%).

Four main facilitators around e-cigarette use were identified

including: 1) There is no reason not to use e-cigarettes; 2) Using

e-cigarettes helps with emotion management; 3) Vaping is a way of

fitting in; and 4) Existing tobacco control policies don’t work for vaping.

E-cigarettes were not perceived as harmful to self and others, which

could explain why Airmen were much less likely to adhere to existing

tobacco control regulations. Subversion was viewed as the healthy

option compared to utilizing designated tobacco use areas due to

the potential exposure to traditional tobacco smoke. This coupled with

a lack of understanding about e-cigarette regulations and difficulties

with enforcement, promoted use among this young adult population.

Conclusion: Findings suggest that e-cigarettes are used for similar

reasons as traditional tobacco products, but their unique ability

to be concealed promotes their widespread use and circumvents

existing tobacco control policies. In order to see reductions in use,

environmental policies may need to be paired with behavioral

interventions at the personal and interpersonal level.

Keywords

E-cigarettes; Vaping; Electronic cigarettes; Military; Young adults; Designated tobacco use areas; Policy

Introduction

With the introduction of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) to

the market in 2006, there has been a dramatic increase in their use. A recent nationally-representative survey in the United States (U.S.)

indicates that past 30-day e-cigarette use among 18-24 year olds

has increased significantly from 2.4% in 2013 to 7.6% in 2018 [1,2].

Similarly, during that same time period e-cigarette use increased from

5.4% to 15.3% among 43,597 newly enlisted Airmen (called Airmen

regardless of gender or rank) surveyed about their tobacco use prior

to enlistment [3].

Although some of the increase in e-cigarette use is based on

their perceived safety over conventional cigarettes [4], much is still

unknown about the health risks associated with using e-cigarettes.

Recent literature suggests that e-cigarettes may place users at

increased risk for lung disease due to exposure to high levels of

ultrafine particles and other toxins [5-7]. Additionally, e-cigarette use

is associated with increased use of other tobacco products one year

later among recently enlisted Airmen. Klesges et al. found that current

e-cigarette-only users at baseline were 6.4 times as likely to convert

to conventional cigarette use and 10.1 times as likely to convert to

non-cigarette tobacco product use (e.g., smokeless tobacco, hookah,

cigars) at a one year follow-up when compared to never-users [3].

Given the conversion rate between e-cigarettes and traditional

forms of tobacco (e.g., cigarettes and smokeless tobacco), the health

impact of traditional tobacco, and the probable health effects from

e-cigarette use alone [5], the growing prevalence of e-cigarette use

among young adults may increase health risks while leading to

significant financial costs, particularly for young adults entering

the military. For instance, the Department of Defense (DoD)

spends on average $1.6 billion annually treating tobacco-related

morbidity among active duty military personnel (e.g., medical care, hospitalizations, lost work days) [8].

Although the military has taken steps to reduce tobacco use

over the past several decades, traditional policies may be limited

in their effectiveness for non-cigarette tobacco products, such as

e-cigarettes. Airmen have an enforced abstinence period during Basic

Military Training (8 ½ weeks) and the first four weeks of Technical

Training which appears to reduce cigarette smoking by 18% among

Airmen who reported smoking prior to joining the Air Force [9].

Furthermore, Airmen are not allowed to use tobacco during the duty

day (between breakfast and dinner) throughout Technical Training

[10], which can last up to 18 months; however, the effectiveness of

this policy is unclear. A previous review of the literature found that

while interventions may reduce the rate of illegal sales to youth

initially, lack of enforcement and the ability for youth to acquire

tobacco from social sources may undermine their effectiveness [11].

In the Air Force, the majority of former users of traditional tobacco

products re-initiate after the ban is lifted and many non-users start

using tobacco for the first time in Technical Training [12,13]. While

even less is known about the effectiveness of these policies with regard

to e-cigarette use, this high rate of (re)initiation suggest that other

factors, such as peer influences or enforcement issues may limit the

effectiveness of these environmental interventions.

In October 2019, the DoD removed e-cigarettes from its shelves

[14]. Unfortunately, research suggests that Airmen do not primarily

purchase e-cigarettes on base, limiting the potential effectiveness

of an on-base availability policy for e-cigarettes [15]. Targeted

marketing and price promotions for military personnel may further

reduce the effectiveness of DoD policies. For instance, JUUL, a

leading e-cigarette company, recently launched the heroes.juul.com

website, which is devoted to targeted marketing (e.g., promotional

videos featuring active duty and veterans) and price promotions (e.g.,

$1 dollar JUUL starter kits) for military personnel and veterans [16].

Therefore, it may be necessary to fully explore the environmental

facilitators of e-cigarette use, as the most promising solutions to

decrease use may be different from the traditional toolbox. Given

the high prevalence of e-cigarette use among new recruits entering

the military, understanding the facilitators of e-cigarette use in

the military population may be an important bellwether for other

vulnerable populations (e.g., non-college attending young adults).

Thus, the current study sought to identify facilitators of e-cigarette

use at a personal (e.g., individual-level characteristics, beliefs, and skills

related to tobacco use), interpersonal (e.g., friend and social network

influences), and environmental level (e.g., cultural values, norms

and the built environment) among Airmen undergoing Air Force

Technical Training. Given that most of the tobacco use (re)initiation

has traditionally occurred during Technical Training [12,13,17], it

is important to understand what factors are influencing Airmen to

use e-cigarettes during this high risk time, particularly since they

are increasing in popularity and existing tobacco regulations may

be limited in effectiveness. These findings will inform intervention

and policy efforts for youth and young adults who have similarly

experienced a rise in e-cigarette use due to targeted marketing and

price promotions [18].

Materials and Methods

This study is a qualitative exploration of the tobacco experience

of Airmen in Technical Training (referred to as Airmen for the

remainder of the manuscript), Military Training Leaders (MTLs) and

Technical Training Instructors (TTIs). Data were collected as part of

a larger study exploring factors predicting tobacco use among Airmen

during Technical Training. This paper presents findings relevant to

personal, interpersonal, and environmental facilitators of e-cigarette

use. In this study, we discuss the results of focus groups with Airmen

undergoing Air Force Technical Training, as well as focus groups of

MTLs and TTIs across the five largest Technical Training schools

where the majority of non-prior service Airmen are trained. Study

procedures were approved by the 59th Medical Wing Institutional

Review Board.

Participants and recruitment:

We conducted a total of 22 focus groups (N=164 participants)

among Airmen (n=10), MTLs (n=7), and TTIs (n=5) from July 2018

to February 2019 at Joint Base San Antonio - Fort Sam Houston and

Lackland Air Force Base (AFB), Goodfellow AFB, and Sheppard

AFB in Texas and Keesler AFB in Mississippi. MTLs are the direct

supervisors of Airmen, ensuring they are where they are supposed

to be and dispensing disciplinary action. TTIs are responsible for

teaching the specific skills required for that career field. While MTLs

are always active duty, TTIs can be active duty or civilians (typically

Airmen who have separated or retired from the military). For this

study, Airmen volunteers were recruited during their out-processing

week at the end of their Technical Training when they were receiving

health-related briefings. MTL and TTI volunteers were recruited

through a recruitment email sent by the Senior MTL at each base.

Participants had to be at least 18 years of age and could be either a

tobacco or non-tobacco user.Focus group procedures:

Protocols for the focus group were developed for users and nonusers

as well as MTLs and TTIs. The focus group questions targeted

the following domains: (1) personal experience with tobacco, (2)

facilitators of tobacco use on base, (3) barriers to tobacco use on base,

and (4) strategies to reduce tobacco use among Technical Trainees.

This paper focuses specifically on data related to e-cigarette use.Focus groups were conducted by two of five trained non-military

researchers in a private room without leadership present in order to

promote an open and safe environment. Each focus group contained

one moderator and at least one note-taker. Participants were

provided with an informational consent letter and verbally consented

to participate. Focus groups contained, on average, 7 participants,

ranging from 4 to 11 participants, and took on average 45 minutes to

complete. Airmen focus groups were separated by tobacco use status

(n=7 with tobacco users, n=2 with non-users, n=1 with users and

non-users). All MTL and TTI focus groups were mixed with tobacco

users and non-users. Participants were provided with food during the

focus group. Responses were anonymous and audio-recorded.

Analysis:

Transcripts of focus groups were transcribed by Datagain.

Transcripts were checked by researchers before coding. A hybrid deductive-inductive approach was used to code transcripts. Two

trained research staff members coded each transcript. Coders met to

resolve discrepancies and came to agreement. If an agreement could

not be reached, a third coder was brought in to resolve discrepancies.

The research team used NVivo (v12) software to manage the coding

process.To facilitate the first pass of coding, a codebook was developed

using the social ecological model, overarching research questions

from the grant, and evidence from the literature. As mentioned above,

the primary domains within this initial codebook were facilitators

and barriers of tobacco use during training, personal experiences with

tobacco and strategies to reduce tobacco use among trainees. Initial

codes within domains were identified based on the literature. Next,

researchers reviewed meaning units within each discrete code to

ensure adherence to operational definitions and to determine whether

codes should be merged or sub-coded. Additionally, meaning units

within codes were categorized based on the specific tobacco product

mentioned, including e-cigarettes. Finally, individual codes were

organized into larger categories.

Results

Of the 164 participants, 83 (50.6%) were Airmen, 48 (29.3%)

were MTLs and 33 (20.1%) were TTIs. The majority of participants

were male (77.4%) and tobacco users (72.0%). The most commonly

used tobacco product across all participants was cigarettes (42.7%),

followed by e-cigarettes (28.0%) and smokeless tobacco (22.6%).

Almost a third (28.7%) of participants reported using more than one

tobacco product. E-cigarette use was much more common among

Airmen (76.1%), compared to MTLs (10.9%) and TTIs (13.0%).

Airmen, MTLs and TTIs were asked what about the Technical

Training environment facilitates tobacco use. Four main facilitators

around e-cigarette use were identified including: 1) there is no reason

not to use e-cigarettes; 2) using e-cigarettes helps with emotion

management; 3) vaping is a way of fitting in; and 4) existing tobacco

control policies don’t work for vaping. Facilitators are described in

detail in the following sections and supported by quotations from

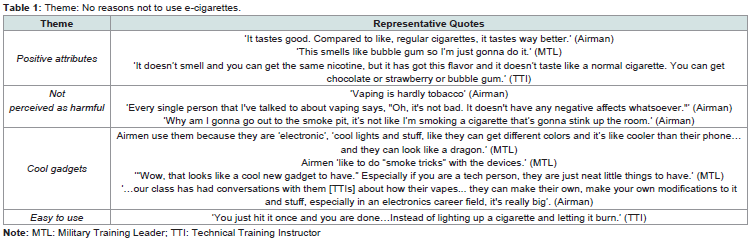

Airmen, MTL and TTI focus group participants in Tables 1-4.

No reasons not to use e-cigarettes:

A number of reasons emerged under the idea that there is no

reason not to use e-cigarettes (Table 1). Specifically, Airmen, MTLs and TTIs mentioned that e-cigarettes had many positive attributes,

were not perceived as harmful, were cool gadgets and were seen as

easy to use.Airmen, MTLs and TTIs all discussed the perception that

e-cigarettes are not (perceived as) harmful. One Airmen said,

‘Vaping is hardly tobacco.’ A MTL thought that Airmen don’t realize

the harms of e-cigarettes, and think ‘this smells like bubble gum so

I’m just gonna do it.’ A TTI said, ‘it doesn’t smell and you can get

the same nicotine, but it has got this flavor and it doesn’t taste like

a normal cigarette. You can get chocolate or strawberry or bubble

gum.’ E-cigarettes were also seen as not harmful in terms of time

required; a TTI said, ‘You just hit it once and you are done…Instead

of lighting up a cigarette and letting it burn.’

Several MTLs thought that Airmen used them because they were

‘electronic’, ‘cool lights and stuff, like they can get different colors and

it’s like cooler than their phone…and they can look like a dragon.’

They also mentioned that Airmen ‘like to do “smoke tricks” with

the devices.’ E-cigarettes were frequently referred to as ‘faddish’,

particularly in certain career fields, such as ‘an electronics career field’

(Airman).

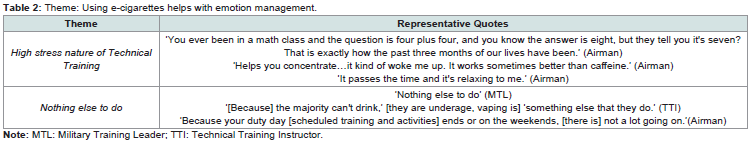

Using e-cigarettes helps with emotion management:

Another consistent reason that was identified was emotion

management. This included using e-cigarettes to cope with the high

stress nature of Technical Training as well as periods of time when

they have nothing to do, particularly on weekends and after the

duty day (Table 2). One Airmen described the challenging training

environment as follows: ‘You ever been in a math class and the

question is four plus four, and you know the answer is eight, but they

tell you it’s seven? That is exactly how the past three months of our

lives have been.’ Another Airmen mentioned how the perception

that vaping could relieve stress promoted its use among Airmen

in Technical Training. Similarly, several Airmen felt that using

e-cigarettes ‘helps you concentrate…it kind of woke me up. It works

sometimes better than caffeine.’ Some Airmen mentioned that they

just enjoyed the act of smoking, ‘it passes the time and it’s relaxing

to me.’E-cigarette use was also seen as an activity that the Airmen

could engage in to manage boredom. A Military Training Instructor

mentioned that in Technical Training, there is ‘nothing else to do’

during their free time. Another instructor pointed out that because ‘the majority can’t drink,’ because they are underage, vaping is

‘something else that they do.’

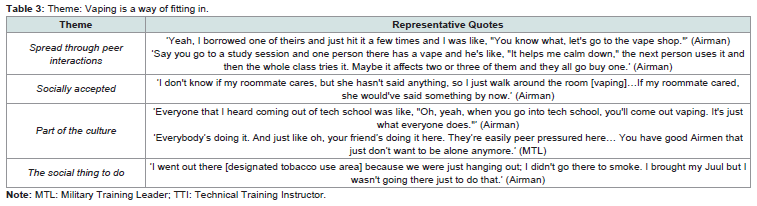

Vaping is a way of fitting in:

Another facilitator of vaping in Technical Training was that it

was spread through peer interactions, socially accepted, part of the

culture, and the social thing to do (Table 3). One TTI described it as,

‘I think smoking’s the same, but the toys have changed.’ MTLs also

mentioned that vaping was spread through ‘peer to peer’ interactions.

Supporting this idea, a number of Airmen mentioned borrowing

an e-cigarette for the first time in Technical Training from a fellow

Airman. Airmen, MTLs and TTIs all discussed how common it was

for Airmen to vape in their rooms, even with a roommate that didn’t

use tobacco. Several MTLs mentioned that Airmen were not always

willing to report to the MTLs when their roommates were vaping in

their rooms. Vaping was also seen as part of the culture of Technical

Training, and popular among certain career fields. A number of

Airmen mentioned how vaping had a social component in Technical

Training. One Airmen mentioned that they go to the designated

tobacco use areas outside of their dorms for social reasons, while a

TTI said Airmen have vaping parties where ‘they see who can blow

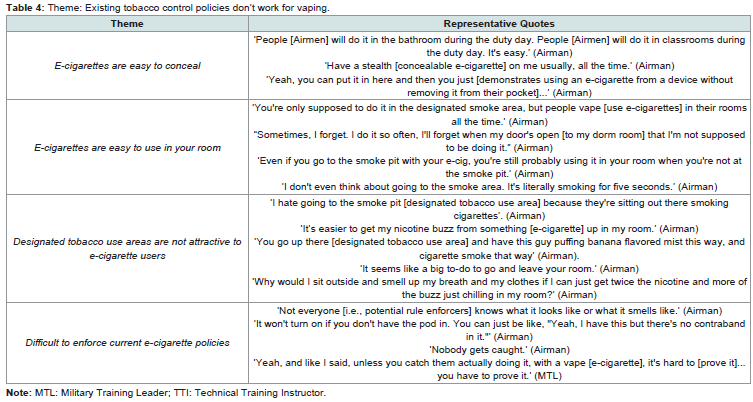

out the most smoke.’Existing tobacco control policies don’t work for vaping:

Existing tobacco control policies were seen as ineffective given

that e-cigarettes are easy to conceal and use in your room, current

designated tobacco use areas were not attractive to e-cigarette users,

and the difficulty in enforcing current e-cigarette policies (Table 4).

A consistent theme from Airmen, MTLs and TTIs was that Airmen

were vaping in their dorm rooms, computer labs, bathrooms and

classrooms despite policy restrictions limiting their use during the

duty (training) day and restricting tobacco use to designated areas

around the military base.One reason Airmen reported using e-cigarettes outside of the

designated tobacco use areas was that they felt they were easy to

conceal. Airmen were not concerned about getting caught with them

because some e-cigarettes are small and the pod (which contains

the nicotine liquid) can easily be removed. Therefore, if they did get

caught with one on them they could remove the pod and wouldn’t

get in trouble for having it when they weren’t supposed to during

their duty day (e.g., when they were in class or training). In fact, some

Airmen even mentioned that although they liked the modifiable

e-cigarettes more than the smaller rechargeable pod e-cigarettes

(e.g., JUUL e-cigarette), they chose to keep ‘stealth’ e-cigarettes with

them during the duty day. One Airman even demonstrated how they

could easily put a small rechargeable pod e-cigarette in the upper arm

pocket of their uniform and use it without anyone knowing what they

were doing.

Many Airmen reported vaping in their rooms. Even among those

who went to the designated tobacco use areas, many still reported

vaping in their rooms. Several Airmen mentioned that leaving their

room to go to the designated tobacco use area felt like a hassle because

of the heat or it wasn’t worth making a trip all the way outside.

Airmen also reported vaping in their dorm rooms was because they

didn’t want to be exposed to secondhand smoke at the designated

tobacco use areas. Airmen mentioned that when they visited the

designated tobacco use areas they ‘got a headache because there were

so many different things going on.’ There was also some confusion as

to whether the Airmen are allowed to use e-cigarettes in their rooms.

One Airman when asked if they were allowed to use e-cigarettes in

their dorm rooms said, ‘I have no idea, but I do it.’ While another

Airman said, ‘I forget [the rule] all the time.’ Many Airmen felt like

the rules were not enforced. However, the MTLs and TTIs expressed

how it was hard to catch Airmen in the act of vaping.

Discussion

The current study sought to identify facilitators of e-cigarette

use among Airmen undergoing Technical Training for the purpose

of informing future intervention and policy efforts for youth and

young adults. While use was initially motivated by factors that

have been previously associated with traditional forms of tobacco

(e.g., entertainment value, flavor options, and use as an emotion

regulation tool), continued use was facilitated by the unique design

of e-cigarettes which allowed for users to easily circumvent existing

tobacco control regulations.

Airmen’s use of e-cigarettes was motivated by several perceived

benefits, such as their entertainment value and use as an emotion

regulation tool. Airmen reported using e-cigarettes to help them

relax or calm down, or even to help them concentrate. These findings are similar to reasons given for use of other non-cigarette tobacco

products, like hookah. Young adults have reported using hookah

because of the social aspect, they enjoyed the taste, and smoking

hookah produced a calming/relaxation effect [19]. Additionally,

Airmen in the sample were drawn to the features of the e-cigarettes,

such as lights, flavors and the ability to do smoke tricks. Previous

literature has shown that flavors are a primary reason for e-cigarette

use among young adults [20-23]. However, in 2020, the Food and

Drug Administration (FDA), banned mint- and fruit-flavored

e-cigarette liquids except for larger, less discrete tank-based systems

or disposable pods. It remains to be seen how this new limitation

will impact e-cigarette use among young adults, given that most

e-cigarette users purchase flavors other than tobacco [20].

Use of e-cigarettes was reinforced by the unique design of

e-cigarettes, affording users with a product that is both discrete

and easy to use. Despite explicit policies banning the use of tobacco

products during the duty day, many Airmen mentioned that

e-cigarettes could easily be concealed and used throughout the day.

Previous studies have found that stealth vaporisers, like JUUL, which

resemble ordinary devices like USB sticks, are often not recognized

by adults, and are therefore popular among youth and young adults

[24,25]. Use indoors was also commonplace in our sample, with

participants reporting use in bathrooms and their dorms despite

explicit rules against use outside of designated tobacco use areas. The

nature of using an e-cigarette (e.g., the ability to take a drag every few

minutes), promoted their use outside of designated areas; it didn’t

make sense to Airmen to go all the way to the designated tobacco use

areas for a drag. Additionally, many Airmen avoided the designated

tobacco use areas because they did not want to be exposed to the

secondhand smoke from burnt tobacco. It may be the case that having

one catch-all tobacco use area that encompasses all types of products

may not be a viable or acceptable option for e-cigarette users.

In addition, a factor that complicated this situation was the

difficulty of catching Airmen using in places or at times that they

were not supposed to, making these rules difficult to enforce. School

districts around the U.S. are facing similar challenges, and as a result

have enacted school-wide flash drive bans, removed the main doors

from student bathrooms and installed vapor detectors [24]. In order

to combat the increase in e-cigarette use among Airmen in prohibited

areas, the Air Force may need to consider implementing similar

measures.

There was also a pervasive theme related to the belief that

e-cigarettes were not harmful, and there was no concern for e-cigarette

secondhand smoke as evidenced by use in dorms with non-smoking

roommates. While e-cigarette secondhand smoke does not contain the

same toxicants as a traditional cigarette, there may be other reasons

for health concern. Studies have shown that e-cigarette users exhale

some of the mainstream vapor, which exposes bystanders to harmful

constituents including heavy metals, nicotine, ultrafine particulates,

volatile organic compounds and other toxicants [26-28]. Another

reason for using in places where e-cigarettes were prohibited was

confusion about whether e-cigarettes were considered tobacco. This

limited awareness of tobacco policies is similar to a study conducted

with 14 colleges and universities, which found that most students

did not know if their school included e-cigarettes in their tobacco policies, or if there were e-cigarette use policies despite the fact that

most students also reported being supportive of having such a policy

[29]. These findings suggest that there is a need for specific policies

related to e-cigarettes, and concerted efforts to raise awareness about

these policies may help clarify the inclusion of e-cigarettes and limit

e-cigarette use. However, additional research is needed to examine

the role that awareness of policies has on e-cigarette use behaviors.

An additional consideration is the implementation of the new

federal Tobacco 21 law, which prohibits the sale of tobacco to anyone

under the age of 21 even if they are military personnel [30]. Almost

half of Airmen are under the age of 21 and thus are no longer able to

buy their own e-cigarette products [20,31]. A common facilitator at

the time of the focus groups (conducted prior to the implementation

of the Tobacco 21 law) was that e-cigarette use was something

Airmen could legally do given there were not a lot of ways Airmen

could spend their free time. With this new legislation, Airmen will no

longer be allowed to purchase tobacco if they are under 21, but will

still be allowed to use tobacco [30]. This could lead some Airmen that

are of age to purchase tobacco products for underage Airmen, which,

if enforced similarly to the rules around alcohol use in the military,

would be classified as ‘contributing to a minor’ and be a punishable

offense leading to a delay in training or even early discharge. Given

that the Air Force already loses $18 million annually on excess

training costs associated with smoking [32], it is likely that this

number will increase under the new legislation. Additional research

is needed to determine if this new regulation is effective at reducing

e-cigarette use among youth and young adults, or if they simply get

these products elsewhere, such as from a friend or roommate, which

may require the Department of Defense to take additional steps to

strengthen their approach to tobacco control. For instance, in the

United Kingdom, plain packaging and a smoking ban in cars with

minors was recently enacted, while other European countries are

striving to reduce the prevalence of youth smoking to under 5% in the

next 15-20 years [33,34]. To achieve this goal, countries like Ireland,

Scotland, Finland, France and the Netherlands have all adopted more

stringent tobacco control policies, such as plain packaging, point-ofsale

display bans and smoke-free playgrounds [33,34]. In 2016, the

Department of Defense put out a policy memo with a similar goal to

reduce tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure by restricting

tobacco use to designated areas on base, creating multi-unit smokefree

military housing, and increasing the price of tobacco [35]. It is yet

to be seen how effective these policies will be at reducing tobacco use

among military personnel.

Strengths and Limitations

The current study was not limited to e-cigarette product use, and

therefore we did not assess all potential reasons for e-cigarette use,

or if specific themes were related to actual e-cigarette use behaviors.

However, the current study provides insights related to perceptions

and beliefs about e-cigarette use among a large and diverse sample

of young adults and can inform future e-cigarette policies and

interventions.

Conclusion

Results highlight how the unique design of e-cigarettes

coupled with perceptions that e-cigarettes are less harmful and

socially accepted promote circumventing existing tobacco control

regulations. In order to effectively reduce the growing prevalence of

e-cigarette use, existing policies and interventions will need to take a

systems approach, in which multiple levels of influence (individual,

community and environment) are considered.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed on this document are solely those of the

authors and do not represent an endorsement by or the views of the

United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, the United States

Government or the National Institutes of Health.

Role of Funding Source

This study was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse

[DA043468]. The National Institute of Drug Abuse had no further

role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of

data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the

paper for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Second Air

Force, the leadership branch for training in the United States Air

Force.