Journal of Addiction & Prevention

Download PDF

Case Report

A Case Study on the Impact of COVID -19 and Social Capital on the Delivery of Medication - Assisted Peer Support

Kravetz ZJ1*, Prakash N1, Lahiri S1, Kunzelman J2, McConnell N2, Fernander A1 and Howard H3

1FAU Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida, USA

2Rebel Recovery, Florida, USA

3FAU Phyllis & Harvey School of Social Work, Florida, USA

*Address for Correspondence

Kravetz ZJ, FAU Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, 777 Glades Road

BC - 71, Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA; E-mail: zkravetz2018@health.fau.edu

Submission: 25 January, 2022

Accepted: 28 June, 2022

Published: 04 July, 2022

Abstract

Introduction: The COVID - 19 pandemic has interfered with

innumerable services in different sectors of the healthcare industry,

including the opioid use disorder recovery community. This communitybased

empirical study explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

and the mutually reinforcing variable of low social capital on the

distribution of medication - assisted peer support.

Methods: Six interviews with leaders of a combined medication

- assisted and peer support group were conducted to identify the

impact of COVID - 19 and low social capital on the substance use

disorder recovery community. Specifically, the recovery community

is incarcerated individuals receiving buprenorphine treatments and

individuals who have been released into the community. Using a

comparative analysis of these interview transcriptswe identified key

areas for procedural changes to reduce the impact of the COVID -

19 pandemic and low social capital on the delivery of medication -

assisted peer support.

Results: Two major themes were elucidated through interviews with

six peer support organization executives (PSOE) and recovery peer

support specialists (PSS): the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the

delivery of medication - assisted peer support services and the effect

of low social capital factors on the delivery of substance use recovery

resources. Secondary to these themes, services have dropped from

daily group activities to difficult-to-schedule weekly one-on-ones, and

constant barriers in communication with participants secondary to the

COVID-19 pandemic.

Discussion: Losing interpersonal relationships of medication -

assisted peer support has disproportionately affected those who

otherwise have none, resulting in a loss of accountability in recovery

efforts. By increasing the duration and frequency of meeting times and

hiring additional service leaders to take on these responsibilities, there

can be a restoration in the value of the program. Additional studies

are needed to further clarify the impact of COVID - 19 on the SUD

recovery community, the complications of low social capital on the

SUD recovery community, and strategies to help mitigate the impact

of COVID - 19 on these issues.

Conclusion: In the opioid recovery community, the distribution and

efficacy of medication - assisted peer support programs have been

severely reduced by COVID - 19 and social capital related factors -

and often a combination of the two. Through this case study, we have

identified targeted areas of improvement to optimize medication -

assisted peer support and other recovery resources.

Keywords

Opioid use recovery; COVID - 19; Medication - assisted peer

support; Opioids, Social capital, Case study

Introduction

In the United States, the past thirty years have seen an increase

in the use of prescription opioids that is commonly known as the

opioid epidemic. The 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health

indicates that8.3% of people, 12 years old or over, have used illicit

drugs in the past year. One approach to treating individuals with

an opioid use disorder is peer support services (PSS). Peer support

involves providing non-clinical assistance from individuals with similar conditions to patients who are recovering from conditions

such as opioid addiction, alcohol addiction, and certain mental health

illnesses. Some programs combine these peer support services with

medication - assisted treatment to help promote “whole - person”

recovery in individuals with substance use disorder. Medication

assisted treatment (MAT), is the combination of opioid agonist

treatment (i.e., methadone) or partial agonist (buprenorphine) with

counseling and other forms of therapy for the treatment of opioid

use disorder. The combination of PSS and MAT is referred to as

“Medication - assisted peer support” [1-3].

Certain programs focus on administering peer support and clinical

treatment to individuals recovering from substance use disorder who

are incarcerated [4]. These programs address the impact of economic

restraints on substance use disorder, breaking cycles of problematic

opioid use, and criminal justice system involvement. Peer support

programs are also imperative for previously incarcerated individuals

who are released from prison as they have a high risk of post - release

opioid - related overdose mortality [5,6].

Social capital framework:

Social capital is a concept that focuses on social relationships

between people that include a variety of factors such as community

networks, civil engagement, and personal connections [7,8].

Community programs that provide recovery support services to

individuals suffering from opioid use disorder (OUD) rely heavily on

social capital. Social capital factors such as a lack of social capital (i.e.,

lack of access to stable income, education, and housing) and lack of

access to civic resources (i.e., community centers and libraries) may

lead to higher rates of opioid - related deaths [9]. Researchers found

that countries with the lowest amounts of social capital tend to have

the highest overdose rates [7].In addition to the lack of access to social capital resources, there

are mass incarcerations of individuals for drug crimes that further

reduce the social capital of individuals with substance use disorder.

Mass incarcerations limit access to social capital resources such as

peer support, educational opportunities, and community resources [7]. In Abbott et al. (2019), researchers found that social capital in

the form of peer networks was important for the promotion of well

- being. Furthermore, researchers found that social capital plays an

important role in the recovery process, which is described using the

concept of “social recovery” [5]. In addition, barriers to social capital

and ultimately “social recovery” negatively impact the recovery

process [6].

Access to programs that provide clinical and peer support

recovery services are also subjected to barriers posed from racism

or bias. Minority communities are disproportionately affected by

substance use disorder and require clinical and peer support recovery

services. And yet, they are also subjected to barriers posed from

discrimination due to race or bias. Researchers found that physician

bias, coupled with inherent healthcare system biases led to obstacles

for minority groups in accessing healthcare providers that offer

medication - assisted opioid recovery.

COVID - 19 has created new challenges for the opioid recovery

community through disrupting many social networks (i.e., in - person

recovery programs) that are central to building social capital. Benton

et al., (2020) details that social capital is valuable and there needs to be

creative methods to support social networks during the COVID - 19

pandemic [10]. This study indicates that there is a new set of concerns

that focus on the current COVID - 19 pandemic in terms of social

capital and ultimately the recovery community.

The COVID - 19 pandemic has strained financial and clinical

resources for healthcare institutions throughout the United States

[1]. One aspect of the healthcare industry impacted by COVID - 19

is the delivery of opioid recovery resources. Specifically, the delivery

of both clinical treatment and peer support services are vulnerable

to the impact of COVID - 19 [11-13]. However, the impact of

COVID - 19 on the delivery of combined clinical treatment and peer

support services to individuals who are incarcerated has not been

fully elucidated. This study explores the impact of COVID - 19 on

the combined medication - assisted and peer support using a social

capital lens to better understand the relationship between the opioid

epidemic, treatment, and recovery.

Methods

The IRB institution from a Southern metropolitan university

reviewed the study and deemed it exempt. Six peer support

organization executives (PSOE) and recovery peer support specialists

(PSS) from a community-based organization with knowledge of

combined medication - assisted peer support were selected for

interviews. We conducted interviews virtually due to the COVID - 19

pandemic.

Since its inception, this recovery - community organization

has provided service provider navigation, linkages with treatment

providers and community resources, advocacy, harm reduction

training, recovery planning, and support groups. This organization

delivers 15,000 hours of recovery support services and 12,264 hours

of outreach annually and serves 1100 individuals experiencing SUD

in the local county each year. Services are tailored to support longterm,

sustained recovery and self-sufficiency; the average length of

participant engagement is 123 days. The staff includes 17 certified

peer specialists, along with 2 full - time Case Management Personnel and two executives. They have also partnered with the county to offer

peer support services in the local jail, coordinated with stakeholders to

provide housing for unsheltered persons residing in an encampment

in a local park, and established a partnership with the Department

of Children and Families to provide services for adults with child

welfare and dependency court cases.

The inclusion criteria included organization leaders who were

involved in implementing the program, such as the CEO of the

recovery program and the clinical director who oversee the medication

- assisted peer support service. To gain insight on the daily operations

of the prison recovery program we included interviews from four

peer leaders who were involved in delivery of medication - assisted

peer support. Peer leaders not involved with the medication - assisted

peer support division of the recovery program were not included.

The research team has an ongoing university-community

partnership with the recovery community organization (RCO) one

area of equal interest is a forthcoming evaluation of the medication

- assisted peer support program. The data collection procedures

consisted of six interviews ranging in length from 30 - minutes to

1 - hour using the CISCO video software WebEx. Participants agreed

to an informed consent and answered six questions listed in below.

We digitally recorded the interviews, and audio files were safely saved

on a password protected computer. Following the interviews, we

uploaded the audio files to the audio - transcription service REV.com.

We then transferred the transcripts to the analysis program NVivo.

Interview questions used to collect data from peer - support

organization executives and peer leaders.

➢ How has delivery of medication - assisted peer services

changed due to the recent COVID - 19 pandemic?

➢ What challenges have you faced in delivering peer services to

participants during the COVID - 19 pandemic?

➢ What changes have you noticed in medication - assisted peer

services participant engagement and satisfaction during the

COVID - 19 pandemic?

➢ What feedback have you received from participants about

delivery of peer services during the COVID - 19 pandemic?

➢ Do you have examples of successful strategies that improved

delivery of peer services during the COVID - 19 pandemic?

➢ How do you navigate delivering peer services to participants

who are different from you?

Upon completion of the interviews, we used constant comparative

analysis methods to analyze the results and develop concepts and

themes via coding information from transcribed interviews (Glaser

et al. 2017). The interview transcripts were uploaded to the NVivo

analytical software and additional coding was performed to generate

themes. After data saturation using a social capital framework,

themes were decided upon after discussion with PSOEs and PSSs. To

promote credibility, we worked closely with the CEO and operations

manager of the peer support organization who provided further

insight to the development of these themes. After member checking,

the community stakeholder agreed that the themes represented

common concerns found in the majority of cases.

Given the questions that still remain as to what exactly

constitutes good qualitative work; several guidelines for writing and

disseminating qualitative manuscripts were followed [11].

Results

Participant Characteristics:

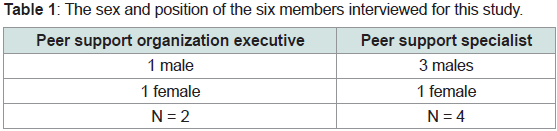

There were N=6 peer support organization executives (PSOE)

and peer support specialists (PSS) who met the inclusion criteria

for participation in the interviews. All peer support specialists were

certified to work in the peer support field and actively work for a

community - based peer support organization in the Southern United

States. Table 1 identifies the interview participants based on position

and gender identification.Themes:

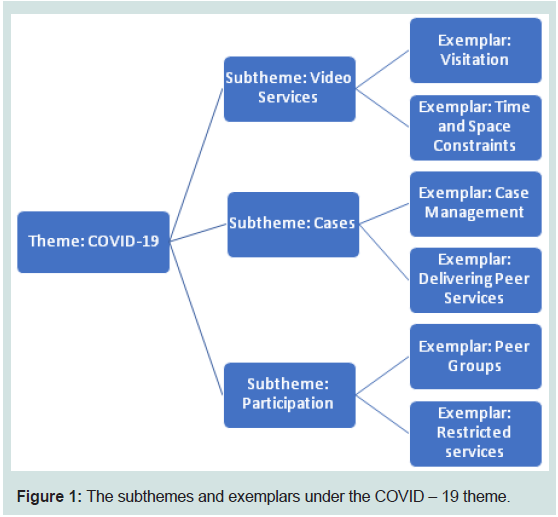

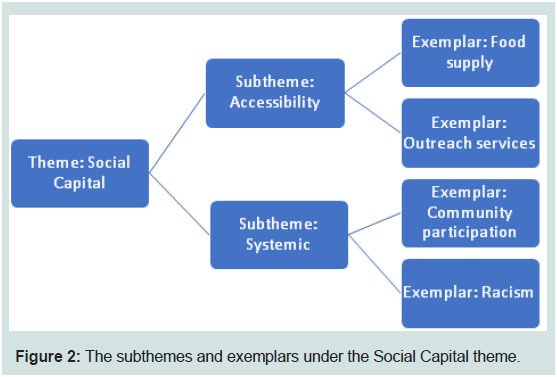

Two major themes were elucidated through interviews with

PSOE’s and PSS’s (considered major if identified in at least half of

the interviews):

➢ The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the delivery of

medication - assisted peer support services and

➢ The effect of low social capital factors on the delivery of

substance use recovery resources.These themes are represented in Figure 1 and 2, below, along

with specific issues (subthemes) related to these themes impeding

access to necessary services.

Theme 1: The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the delivery

of medication - assisted peer support services.

In reference to the COVID-19 pandemic, we identified video

services, cases, and participation as critical subthemes that represented

barriers to medication - assisted peer support.

Video Services:

Within the subtheme of video services, visitation (n=5) and time

& space constraints (n=3) were mentioned by interviewees as issues

reducing access to interpersonal relationships necessary for keeping

program participants motivated and accountable. A PSOE stated

that:“The program participants did not always play nice, everybody

does not communicate well, we were getting mixed messages on

how we could still see them, how we could talk to them, can we have

video conference and what that looks like for delivering services.”This

constant miscommunication with program participants was

compounded by higher-ups telling service leaders that they were:

“…only able to conduct direct services periodically through a video

telecommunications center.” (as stated by a PSS).A PSS mentioned that specifically in the prison dorms, there is

only one video visitation room, a limitation related to COVID-19.

This has, according to a PSOE, caused “A huge shift, that we’re not

able to make the same impact with individuals using substances over

the phone or video call that we would be in person because there are

certain intricacies about when you’re speaking to them that just don’t

translate well over video or other lines of digital communication.”

The new video services format, secondary to COVID-19, has

caused time and space constraints that, although do not sound like a

huge hindrance, create an extra barrier to interpersonal relationships

at the core of peer support. A PSS stated that: “It’s a whole thing to

the set up a fifteen-minute visitation when I can normally just drive to

the prison and go see who I want to see.”A PSOE mentioned a more

severe, yet not uncommon, case: “It took probably six to eight weeks

before we could actually set up a video conference with the guys.”

Cases:

The second subtheme encompasses issues with case management

and the delivery of peer services, secondary to COVID-19 case

changes. When comparing organizational cohesiveness prior to and

during the current pandemic, a PSS stated: “Just staying connected as

an agency and letting our case managers and our supervisors know

what was going on, made it a lot easier for everyone to be on the same page to continue to provide services.”Now that case management

is being done completely remotely, there is disjointedness within

the organization, which has led to vital information regarding

participants’ recovery progress go unnoticed, causing a reduction

in needed services being distributed to those who need them

immediately [15].A PSOE stated the following that highlights the shift from live

meetings with providers to the distance - based format, which has

caused an overextension of service leaders’ duties outside of the norm:

“We had our case managing entity hold calls with all the providers

that are in this network every week. Having these calls in place where

everybody was that gets paid by the managing entity here; we were all

on calls at 8:30 every morning on Monday, Wednesday and Friday”

[17-19].

Prior to the pandemic, peer services themselves were delivered in

a variety of different ways, including “outreach work from going into

the local communities, all the respite facilities” (according to a PSS).

This scope has now been severely limited. This again has changed the

efficacy and crux of the program itself. An additional PSS stated that:

“Obviously, when I received peer services, before I became a peer

counselor, I was able to make better connections with folks face to

face, person to person; you’re able to read body language better, and

all in all just build trust a little bit easier” [20,21].

Participation:

The final subtheme elucidated by interviewees (n=3) is a

reduction in participation from program participants themselves,

within peer groups and the other restricted services. Loss of the

central interpersonal relationships provided by medication - assisted

peer support due to difficulty scheduling visits, reduced visitation

time, and one-on-one meetings (rather than daily face-to-face group

work based on The Wellness Recovery Action Plan) has caused

participants to devalue the program itself. A PSS mentions: “I’ve had

one individual a couple months ago that didn’t want to continue

participating in peer services upon release from the program because

he wanted to know what he could get from our organization.”An additional PSS juxtaposes the highly involved curriculum

before and during the current pandemic: “We went from doing

several groups a day collectively and doing several one-on-ones,

keeping constant updates, down to only being able to meet with a

participant via telecommunications maybe once a week for 10 to 15

minutes at a time.”In the same vein, a PSS says: “Delivering services

in the medication - assisted peer support program, it almost became

nonexistent, because we went from doing several groups a day to

none at all” [22,24].

Theme 2: The effect of low social capital factors on the delivery of

substance use recovery resources.

In reference to low social capital, we identified accessibility and

systemic issues as barriers to medication - assisted peer support.

Accessibility Issues:

Participants (n=5) mentioned accessibility to resources as a

barrier to the delivery of medication - assisted peer support. A PSOE

mentions the interruption of the 60-day program (which involves

buprenorphine treatment, peer group activities, and self- reflection): “Frustration with not being able to access to services or for folks who

want to sign up, frustration having their services cut, essentially in the

middle of what’s supposed to be a 60-day program.”Many participants, incarcerated individuals specifically, are

affected by a restriction in program resources. A PSOE mentioned:

“That was a huge shift, but specifically with the medication - assisted

peer support program is that incarcerated individuals are not given

access to phones and computers that would even allow for the delivery

of tele health services in any form” [25].

Issues with access are not localized to program services, however.

Interviewees mentioned general reduced access to food supply as

a barrier faced by those with low social capital. A PSS shared the

following: “People I’ve worked with have always struggled with

obtaining food stamps and following through certain obligations that

they need to, to get these services.” This shifts the program participant’s

focus from recovery efforts to basic survival, further limiting access to

peer support due to participant’s inability to attend meetings. This

compounded with the loss of interpersonal relationships central to

the program itself greatly reduces willingness to participate.

Outreach services have also been severely reduced secondary to

the COVID-19 pandemic, and disproportionately affect those with

low social capital. In reference to the reduction of services themselves,

A PSS mentioned the following: “I don’t know if it’s just because no

contact or we haven’t been able to perform as many outreach services

as of late, but I’ve noticed at least on my end, that there’s been a pretty

significant drop off of participants coming through and signing up for

services.” In reference to how this affects those with low social capital,

A PSOE mentions the difficulty in providing resources to individuals

who are homeless during the COVID-19 pandemic: “It’s harder to get

somebody into housing, because COVID has diverted a lot of housing

money towards individuals who work part time and have been laid

off. We are utilizing a lot of resources, to take care of ensuring that

rent protections are put in, when they’re laid off through no fault

of their own, which means that less individuals are accessing those

things who don’t have jobs.”

Systemic Issues:

Interviewees (n=3) mentioned systemic barriers that further

impede the delivery of medication - assisted peer support. Community

spread of COVID-19 within prisons, compounded with the lack of

telehealth resources for peer support and other recovery services

cause a positive feedback loop for individuals with low social capital

who are becoming more and more disadvantaged in their journey

to recovery. A PSOE states:“Individuals are being arrested for petty

crimes, small time drug possession, that are still being introduced into

the jail and are being exposed to COVID through community spread,

and they’re trying to isolate it as best as possible when realistically

had they adopted a lot of these tactics that we’re using, with the rest

of our community participants much farther back instead of trying

to intentionally bar access for inmates from telehealth services, they

could have potentially prevented an outbreak from even happening

because there would be less contact.”This compounded with race inequities puts minorities at a

higher disadvantage when it comes to accessing recovery services. A

PSOE stated the following:“They explicitly impact black and brown communities at a higher rate than they do white communities because

incarceration and the crimes that are listed on the exemption list, we

know that black and brown people are charged or arrested for those

crimes at a higher rate than white people despite data showing an

equal rate of committing of crimes across white people to black and

brown people.”

In addition, interviewees mentioned that community participation

is imperative for keeping individuals involved in medication - assisted

peer support. Without this collaboration, individuals are not being

motivated or held accountable for their recovery efforts. A PSOE

mentioned the following:“It’s more difficult to stay in contact with

individuals who are suffering from opioid use disorder if they’re not

being referred back into the community program, which is where

most of the navigation of care would take place upon release.”

Discussion

Two main themes, the effect of COVID-19 and the effect of

low social capital, were found to greatly impede the delivery of

medication - assisted peer support services and substance abuse

recovery resources. Within these issues, specific subthemes were

identified that uphold these barriers: time and space constraints,

reduced efficacy in communication and case management, almost

complete loss of interpersonal activities, reduced outreach services

to those disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and low social

capital, and, in the case of prison inmates, restriction of necessary

resources altogether. These results are consistent with other findings

in literature that highlight the impact of COVID - 19 on the separate

delivery of medication - assisted treatment and peer support [13].

There is little fidelity in delivering adequate services in “15-minute

sessions,” especially via video systems. One area of improvement

is increasing frequency and duration of these meetings, resuming

the building of interpersonal relationships and support systems for

program participants. This may require hiring of additional service

leaders to accommodate their rising responsibilities since the

COVID-19 pandemic began. Increasing frequency of meetings can

also improve the case management issues identified; specifically: more

frequent meetings between service leaders and program participants

can increase the amount of case-relevant information being relayed

to case managers and supervisors who can make important decisions

regarding a participants’ care.

Interviews conducted with peer service leaders indicate the

necessity of initiatives that address the lack of face - to - face

interaction and outreach services that occur secondary to the COVID

- 19 pandemic. The Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP), a

personalized and structured wellness process, was implemented as a

substitute for live interaction with peer leaders and has been shown

to have positive outcomes for recovery participants [6]. Service

outreach has been greatly reduced secondary to COVID-19, and

this disproportionately affects individuals with low social capital (ex.

incarcerated or previously incarcerated individuals and individuals

experiencing homelessness). Recent studies have shown that the

creation of solutions for these individuals would increase program

enrollment, reduce the chance of relapse or overdose, and reduce

the possibility of these individuals, who are also at a higher risk of

being arrested for petty drug-related crimes, from entering prison systems where there is a risk for community COVID-19 infection

and lack of telehealth services and other recovery services [8]. The

crux of medication - assisted peer support services is its creation of

interpersonal connections for those who otherwise have none. With

the services that foster these connections currently running at a small

fraction of what once was, participants from lower socioeconomic

backgrounds are struggling to see the point of continuing in the

program, especially when other more pressing issues, like accessing

food, shelter, and safety are at the current forefront of their day-to-day

[25-27]. Further studies can elucidate the effect a lack of interpersonal

connections has on individuals of minority groups.

Limitations

The results of this case study are limited by the structure of the

study, sample size, and potential for bias. The interview structure of

this study allows the risk for error bias based on interview questions

and interviewee response. The relatively small sample size (N=6)

is a limitation for making generalized conclusions. However, this

small sample size is typical of case studies, especially those studies

of new ideas, and may be transferable to other community recovery

organizations (Bacchetti et al., 2011). Accounting for these limitations,

important conclusions are identified from the results of this study.

Conclusion

During the COVID - 19 pandemic, obstacles have arisen

throughout the healthcare field. One specific demographic that

has been negatively affected is the opioid recovery community. In

the opioid recovery community, the distribution and efficacy of

medication - assisted peer support programs have been severely

reduced by COVID - 19 and social capital related factors - and often

a combination of the two. This empirical study has led us to identify

targeted areas of improvement to optimize medication - assisted peer

support and other recovery resources. Further studies are necessary

to create specific solutions and to identify additional areas of these

recovery programs that are being negatively affected. These can in

turn lead to the improvement of medication - assisted peer support,

aiding those battling substance abuse and helping to reduce relapses

and drug - related injuries during this pandemic. Ideally, these

targeted improvements would result in far-reaching and lasting

improvements in the system that would benefit the substance use

recovery community beyond the COVID - 19 era.