Journal of Clinical and Investigative Dermatology

Clinical Characteristics of Non-Melanoma Skin Cancers Recurring within 5 years after Mohs Micrographic Surgery: Single Institution Retrospective Chart Review

Tina Vajdi1, Robert Eilers2, and Shang I Brian Jiang2*

- 1Department of Dermatology, School of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA

- 22Department of Dermatology, Dermatologic and Mohs Micrographic Surgery Center, School of Medicine, University of California San Diego,CA, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Shang I Brian Jiang, Department of Dermatology, Dermatologic and Mohs Micrographic Surgery Center, University of California, San Diego, 8899 University Center Lane Suite 350, CA 92122, USA, Tel: (858) 657-8322; Fax: (858) 657-1293; E-mail: s2jiang@mail.ucsd.edu

Citation: Vajdi T, Eilers R, Jiang SI. Clinical Characteristics of Non-Melanoma Skin Cancers Recurring within 5 years after Mohs Micrographic Surgery: Single Institution Retrospective Chart Review. J Clin Investigat Dermatol. 2017;5(1): 4

Copyright © 2017 Vajdi T, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical & Investigative Dermatology | ISSN: 2373-1044 | Volume: 5, Issue: 1

Submission: 25 November, 2016| Accepted: 02 January, 2017| Published: 10 January, 2017

Abstract

Background: Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is used to treatcertain high-risk non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC) due to its highcure rate. However, clinical recurrences do occur in a small numberof cases.

Objective: We examined specific clinical characteristicsassociated with NMSC recurrences following MMS.

Methods: We employed a retrospective chart review of the 1467cases of NMSC that underwent MMS at UC San Diego from January 1,2008 through December 31, 2009. A total of 356 cases were excludeddue to lack of follow-up.

Results: Five (0.45%) of 1111 cases developed recurrencesof NMSC at the site of MMS. There were 741 cases of basal cellcarcinomas (BCC); 3 were recurrences (0.40%). There were 366 casesof squamous cell carcinomas (SCC); 2 were recurrences (0.55%).Review of MMS histopathology of these recurrent tumors showed thatthere were no errors or difficulty with the processing or interpretationof the slides.

Conclusion: Five-year recurrence rate of NMSC following MMSat our institution is below the reported average. Our retrospectivechart review identified specific clinical characteristics associated withNMSC recurrence including a history of smoking, anatomical locationon the cheeks, ears or nose, and a history of immunosuppression forSCCs.

Introduction

Over one million new cases of non-melanoma skin cancers(NMSC) are diagnosed annually in the United States, and the prevalence of skin cancer is five times higher than that of breastor prostate cancer [1,2]. The incidence of NMSC is increasing worldwide, especially in the United States, Europe and Australia, most likely due to a growing, aging population as well as prolonged ultra violate exposure [3,4].

NMSC most commonly include basal cell carcinomas (BCC) andsquamous cell carcinomas (SSC), and many factors influence theirdevelopment. NMSC such as BCC and SCC most frequently occur onthe face and neck due to longitudinal UV exposure [5]. Additionally, patients who are immunosuppressed and/or are organ transplant pients have significantly increased risk of developing NMSC. There is a 65 to 250-fold increase in developing squamous cell carcinoma and a 10-fold increase in basal cell carcinoma in these patients. In addition to developing higher numbers of NMSC, recent studies have that many immunosuppressed patients have NMSCs with aggressive subclinical extensions [6,7]. Associations have also been found between smoking and squamous cell carcinomas, with a higher risk in current smokers than former smokers [8].

The gold standard for the removal of a high risk NMSC is Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) because of its low recurrence rate and tissue sparing technique. Although there are a number of treatment modalities for NMSC including surgical excision and lectrodessication and curettage, MMS continues to be the most advantageous. Studies have shown cure rates for surgical excision as95% for NMSC less than 2 cm and 84% for electrodessication and curettage for NMSC greater than 2 cm [9]. Unlike other modalities, MMS offers a superior cure rate of 99% within 5 years for primary BCCs, and slightly lower cure rate for primary SCCs [10]. Further analysis has shown the cost effectiveness of MMS in treating high risk MSC since very high cure rates limit subsequent procedures while maximizing tissue preservation and cosmesis [10,11].

Recurrence rates following MMS have been variable as multiplestudies express different recurrence rates. Primary BCCs have about a 1% risk of recurring [10,13]. However, recurrent BCCs have a higher recurrence rate of 10.4% following MMS [6]. Primary SCCs have a recurrence rate of about 2 to 3%, while recurrent SCCs have a 6-10% recurrence rate following MMS [14,15].

In this study, we aim to identify risk factors that lead to NMSCrecurrences.

Methods

We reviewed the medical records of 1467 cases of MMS forNMSC performed at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD)Dermatologic and Mohs Micrographic Surgery Center from January1st, 2008 through December 31st 2009. A retrospective chart reviewwas used to identify cases of NMSC recurrence within 5 years of MMS at our institution. In this IRB approved study, there were 611 cases in which patients lacked 5 years of follow-up at UCSD post MMS. They were contacted via telephone and asked if they had further treatments at the site of the original MMS. Of the 611 cases not followed-up at UCSD, 346 were unable to be reached over the phone (loss to followup, new phone numbers, or death) and were excluded from the study. This included 128 SCCs, 217 BCCs, and 1 atypical fibroxanthoma. Three patients who answered the phone were unable to say with certainty if they had further treatments or not on the same location of the initial MMS, and were also excluded from the study. Seven patients had incomplete information in their charts to determine if they had a recurrence in their NMSC, and these cases were excluded. Therefore, 356 cases were excluded from the study.

Retrospective chart review of the 1111 cases included in the study was performed and further subdivided into 741 BCC, 366 SCC and 4 other unusual cutaneous tumors (dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, porocarcinoma, atypical fibroxanthoma, and sebaceous carcinoma). Recurrent cases were defined by the same type of NMSC, occurring at the same site as the previous MMS. For the recurrent cases, we gathered information regarding the patients’ NMSC histopathology, smoking status, immunosuppression, anatomical location and time to recurrence. Slides from the initial MMS were also reviewed to ensure that there was no error or difficulty with slide interpretation or processing of the slides that would lead to the recurrence.

Results

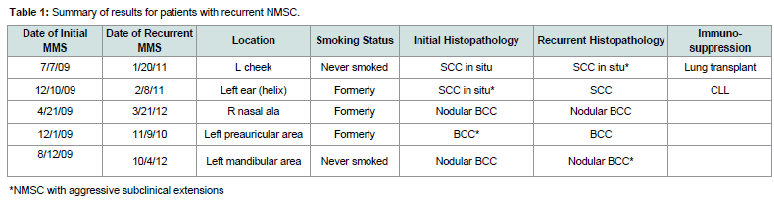

Five (0.45%) cases of recurrent NMSC within 5 years werefound in the 1111 cases of MMS performed in 2008 and 2009. Allfive patients underwent MMS within a few months of their NMSCdiagnosis. The time to recurrence ranged from 11 to 38 months postinitial MMS with an average of 23.6 months. A summary of the datacollected can be found in Table 1.

Demographics of patients with recurrences

All 5 patients (3 male and 2 female) with recurrences werebetween the ages of 60 and 96. The average age for the initial MMS inthese patients was 73 and the average age of MMS for their recurrencewas 74.6.

Histopathology of NMSC-BCC, SCC and other subtypes

There were 741 cases of BBC, 366 cases of SCC and 4 cases ofother unusual types of NMSC. There were no recurrences found inthe other usual cutaneous tumors including dermatofibrosarcomaprotuberans, atypical fibroxanthoma, porocarcinoma and sebaceouscarcinoma. There were 3 recurrences of BCC (0.40%) and 2 recurrences of SCC (0.55%).

Two of the three BCC recurrences arose from low-risk nodularBCCs. One of the two SCC recurrences arose from a SCC in situwhile the other arose from a biopsy-proven SCC in situ, which wasupstaged to a SCC at the time of initial MMS.

The initial MMS histopathology of the recurrent cases wasreviewed and no errors or difficulty were noted with the processingor interpretation of the slides.

Immune status

Both of the SCC recurrences occurred in immunosuppressedpatients (one patient with history of lung transplant and another withhistory of chronic lymphocytic leukemia). The three patients withBCC recurrences were not immunosuppressed.

Anatomic distribution of recurrencesAll recurrent cases of NMSC were located on the face. Four of thefive recurrences involved the left side of patients’ faces, specifically, the left medial cheek, left auricular helix, left preauricular cheek area,and left mandibular cheek. The final recurrence occurred on the right nasal ala (Figure 1).

Smoking status

Three patients with recurrences also had a history of cigarettesmoking. They smoked 0.75 packs per day for 17 years, 1 pack a dayfor 4 years, and 0.75 packs a day for 15 years.

Mohs stages and final surgical margins

The number of stages taken for MMS ranged from 1 to 5 (mean2.6 stages) initially in patients with recurrences, and from 2 to 4 stages (mean 2.6 stages) for their recurrence. Their final postoperative Mohs surgical margins from the longer axis ranged from 2 to 21 mm (mean 12.2 mm) for the initial NMSC, and from 4 to 56 mm (mean 17.8 mm) for the recurrences. Aggressive subclinical extensions (ASE), defined as greater than 3 MMS stages and greater than 1.0 cm final surgical margins, were found in two patients with SCC recurrencesand two patients with BCC recurrences as shown in Table 1. Two of the patients had ASE in their initial surgery and two had them in their recurrent surgery.

Discussion

Our single institution retrospective study revealed a lower than historical recurrence rate in non-melanoma skin cancers after Mohs micrographic surgery. Only 5 (0.45%) of the 1111 cases of MMS performed in 2008 and 2009 had a recurrence within 5 years.Further follow up with these five cases showed no evidence ofanother recurrence following the second MMS. The range of furtherfollow up for these patients was 12 to 67 months post-MMS for therecurrence (mean 47.4 months). Review of MMS histopathology ofthese recurrent tumors showed that there were no errors or difficulty with the processing or interpretation of the slides.

There are reports of histologic subtypes being a risk factor forrecurrence [16,17]. Our study did not show a correlation between aggressive histopathologic subtypes of NMSC and recurrence. Immunosuppressed status, including history of solid organ transplant and hematologic malignancies, has been linked to SCC development and aggressive subclinical extensions [18,19] due to their chronic immunosuppressed status and decreased cutaneous immunosurveillance [6,7]. The two patients with SCC recurrences in our study were immunosuppressed (lung transplant and chronic lymphocytic leukemia).

We identified specific clinical characteristics associated withNMSC. All five of the recurrent cases of NMSC were localized tothe face, specifically the upper cheek, ear, pre-auricular area andnose (Figure 1), with the final case located partially in the H zone and extending to the cheek. These findings are consistent with other reports in the literature of recurrences following MMS occurring most often in the H zone of the face [20].

A history of smoking was found in 60% of our recurrent cases.There have been several studies showing positive associationsbetween cigarette smoking and development of NMSCs, especiallySCC development [21,23]. However, other studies failed to show positive associations between smoking and NMSC development [24,25]. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for recurrent NMSC has not been studied, and we have found an association between smoking and recurrent NMSC in our study.

Four out of five of the NMSC recurrences were found to haveaggressive subclinical extensions (ASE) during the first or recurrent surgery. Both patients with SCC recurrences had ASE and two of the three BCC recurrences had ASE. It is known that immunosuppressed patients, especially those with solid organ transplants are more likely to have NMSC with ASE [7]. This is in accordance with our data as both patients with SCC had ASE and were immunocompromised.

A limitation of this study is that it is a single institutionretrospective study that analyzed data of only a two-year period. Since recurrences are rare, further longitudinal and multi-center studies are also warranted to further identity risk factors for NMSC recurrencesafter MMS.

Acknowledgements

The project described was partially supported by the NationalInstitutes of Health, Grant 5T35HL007491. The content is solelythe responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily representthe official views of the NIH.

References

- Jemal A, Tiwari RC, Murray T, Ghafoor A, Samuels A, et al. (2004) Cancer statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin 54: 8-29.

- Stern RS (2010) Prevalence of a history of skin cancer in 2007: results of an incidence-based model. Arch Dermatol 146: 279-282.

- Samarasinghe V, Madan V (2012) Nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Cutan Aesthet Surg 5: 3-10.

- Trakatelli M, Ulrich C, del Marmol V, Euvrard S, Stockfleth E, et al. (2007) Epidemiology of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in Europe: accurate and comparable data are needed for effective public health monitoring and interventions. Br J Dermatol 156 Suppl 3: 1-7.

- Surdu S, Fitzgerald EF, Bloom MS, Boscoe FP, Carpenter DO, et al. (2013) Occupational exposure to ultraviolet radiation and risk of non-melanoma skin cancer in a multinational European study. PLoS One 8: e62359.

- Goldenberg A, Ortiz A, Kim SS, Jiang SB (2015) Squamous cell carcinoma with aggressive subclinical extension: 5-year retrospective review of diagnostic predictors. J Am Acad Dermatol 73: 120-126.

- Song SS, Goldenberg A, Ortiz A, Eimpunth S, Oganesyan G, et al. (2016) Nonmelanoma skin cancer with aggressive subclinical extension in immunosuppressed patients. JAMA Dermatol 152: 683-690.

- De Hertog SA, Wensveen CA, Bastiaens MT, Kielich CJ, Berkhout MJ, et al. (2001) Relation between smoking and skin cancer. J Clin Oncol 19: 231-238.

- Lewin JM, Carucci JA (2015) Advances in the management of basal cell carcinoma. F1000Prime Rep 7: 53.

- Tierney EP, Hanke CW (2009) Cost effectiveness of Mohs micrographic surgery: review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol 8: 914-922.

- Kauvar AN, Cronin T Jr, Roenigk R, Hruza G, Bennett R, et al. (2015) Consensus for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment: basal cell carcinoma, including a cost analysis of treatment methods. Dermatol Surg 41: 550-571.

- Català A, Garces JR, Alegre M, Gich IJ, Puig L (2014) Mohs micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinomas: results of a Spanish retrospective study and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of tumour recurrence. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 28: 1363-1369.

- Alam M, Desai S, Nodzenski M, Dubina M, Kim N, et al. (2015) Active ascertainment of recurrence rate after treatment of primary basal cell carcinoma (BCC). J Am Acad Dermatol 73: 323-325.

- Leibovitch I, Huilgol SC, Selva D, Hill D, Richards S, et al. (2005) Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery in Australia I. Experience over 10 years. J Am Acad Dermatol 53: 253-260.

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr (1992) Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. Implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol 26: 976-990.

- Lang PG Jr, Maize JC (1986) Histologic evolution of recurrent basal cell carcinoma and treatment implications. J Am Acad Dermatol 14(2 Pt 1): 186-196.279-282.

- Clayman GL, Lee JJ, Holsinger FC, Zhou X, Duvic M, et al. (2005) Mortality risk from squamous cell skin cancer. J Clin Oncol 23: 759-765.

- Herman S, Rogers HD, Ratner D (2007) Immunosuppression and squamous cell carcinoma: a focus on solid organ transplant recipients. Skinmed 6: 234-238.

- Wong J, Breen D, Balogh J, Czarnota GJ, Kamra J, et al. (2008) Treating recurrent cases of squamous cell carcinoma with radiotherapy. Curr Oncol 15: 229-233.

- Chren MM, Torres JS, Stuart SE, Bertenthal D, Labrador RJ, et al. (2011) Recurrence after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer: a prospective cohort study. Arch Dermatol 147: 540-546.

- Aubry F, MacGibbon B (1985) Risk factors of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. A case-control study in the Montreal region. Cancer 55: 907-911.

- De Hertog SA, Wensveen CA, Bastiaens MT, Kielich CJ, Berkhout MJ, et al. (2001) Relation between smoking and skin cancer. J Clin Oncol 19: 231-238.

- Boyd AS, Shyr Y, King LE Jr (2002) Basal cell carcinoma in young women: an evaluation of the association of tanning bed use and smoking. J Am Acad Dermatol 46: 706-709.

- Freedman DM, Sigurdson A, Doody MM, Mabuchi K, Linet MS (2003) Risk of basal cell carcinoma in relation to alcohol intake and smoking. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 12: 1540-1543.

- Odenbro A, Bellocco R, Boffetta P, Lindelof B, Adami J (2005) Tobacco smoking, snuff dipping and the risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a nationwide cohort study in Sweden. Br J Cancer 92: 1326-1328.