Journal of Clinical and Investigative Dermatology

Download PDF

Case Report

Oral Lichen Planus Developing after PD-1 Inhibitor Therapy in Two Patients with Malignant Melanoma

Jain N1, Panah E1, Garfield E1, Quan V1, Shi K1, Mohan L1, Yoo S1, Chandra S2, Sosman J2 and Gerami P1*

1Department of Dermatology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, USA.

2Division of Hematology and Oncology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, USA.

*Address for Correspondence:

Gerami P, Northwestern University, Department of Dermatology, 676 N. St Clair St., Suite 1600Chicago, IL, USA, Tel: (312) 695-1413; Email: p-gerami@northwestern.edu

Submission: 30 May, 2019

Accepted: 19 June, 2019

Published: 28 June, 2019

Copyright: © 2019 Jain N, et al. This is an open access article distributed

under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted

use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work

is properly cited.

Abstract

Cutaneous adverse reactions to checkpoint inhibitor therapy commonly

include non-specific dermatitis and pruritus, though the development of

a wide range of dermatologic toxicities has been described, including

lichenoid reactions. Occasional oral mucosal involvement has been

reported, with rare erosive changes. Here, we present two cases of erosive

oral lichen planus developing after PD-1 inhibitor therapy for malignant

melanoma, with one case that later progressed to diffuse cutaneous

involvement. Oral involvement in both cases was treated with topical high

potency steroids and topical tacrolimus. This treatment regimen allowed one

patient to continue immunotherapy and the other to resume immunotherapy

after it was discontinued. These cases support erosive oral lichen planus as

a notable, serious adverse effect of PD-1 inhibitors.

Introduction

Advances in immunotherapy, including the programmed death

1 (PD-1) checkpoint inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab,

have considerably changed the management of advanced malignant

melanoma. These monoclonal antibodies impede binding of PD-1

with its ligand, PD-L1, preventing T-cell apoptosis and stimulating

antitumor response [1]. Cutaneous immune-related adverse effects

from PD-1 inhibitor therapy occur frequently, with non-specific rash

and pruritus among the most commonly reported [2,3]. The extent

of their cutaneous toxicities, however, has yet to be fully identified.

Here, we present two patients with advanced malignant melanoma

who underwent adjuvant therapy with nivolumab and later presented

with erosive oral lichen planus.

Case Presentation

Case 1: A 78-year-old female with a history of Diffuse Large B-Cell

Lymphoma (DLBCL) and malignant melanoma presented to

dermatology clinic for painful erosive lesions on her lower lip

following two months of therapy with nivolumab. She was initially

diagnosed with a stage T2a melanoma of her back in March 2015 and

underwent a 2 cm wide local excision with negative sentinel lymph

node biopsy. Surveillance imaging and subsequent biopsy in March

2016 revealed metastatic melanoma in the lung, treated with wedge

resection. In February 2017, surveillance MRI detected a subcutaneous

nodule of the posterior trunk; pathology confirmed metastatic

disease. After surgical excision of the nodule, the patient was started

on high-dose ipilimumab in May 2017. While on ipilimumab, the

patient developed new foci of disease with subcutaneous nodules

on the back and later on the abdomen. Both lesions were resected Ipilimumab was discontinued, and she was started on nivolumab in

January 2018. After two months of treatment with nivolumab, the

patient presented to the emergency department with progressive

lower lip ulcerations and gingival erosions associated with burning,

bleeding, and difficulty tolerating oral intake secondary to pain. She

was initially treated with valacyclovir without improvement. Viral

culture was negative for herpes simplex viruses 1&2. She was referred

to dermatology for further evaluation. On physical examination, an

extensive 4 cm heme-crusted tender ulceration was noted on the

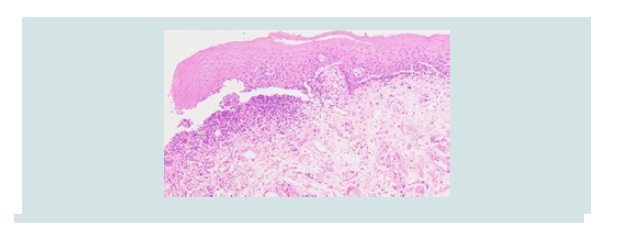

lower vermilion lip (Figure 1). Punch biopsy revealed erosive lichen

planus (Figure 2). Nivolumab was temporarily held, and the patient

was treated with topical clobetasol 0.05% ointment and bacitracinpolymyxin

ointment twice daily for two weeks followed by topical

tacrolimus 0.1% ointment twice daily. Significant improvement in

the lesion was noted after one month of treatment (Figure 3). The

patient resumed immunotherapy after 4 weeks, and her oral lichen

planus remained stabilized with topical therapy. She subsequently

developed bullous lesions on her bilateral shins and feet. Pathology

demonstrated a lichenoid process, and direct immunofluorescence

studies were negative for immune deposits.

Case 2: A 70-year-old male with a history of psoriasis was referred to

dermatology after diagnosis of a T4bN1aM0 melanoma of the right

arm, status post wide local excision and axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy

One of four lymph nodes was positive for melanoma, and the

patient underwent a complete right axillary lymph node dissection

with no additional positive lymph nodes. PET/CT and MRI scans did

not show evidence of metastatic disease. The patient was enrolled in a

clinical trial of adjuvant immunotherapy randomized to nivolumab or

combination ipilimumab/nivolumab in February 2018. Two months

after starting treatment, the patient presented to his oncologist with

a lip ulceration, which was initially treated with topical acyclovir

without improvement. Evaluation by a dermatologist revealed 2

cm heme-crusted erosion on the lower vermilion lip. Punch biopsy

was consistent with oral lichen planus. The patient was started on

topical clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily for one week followed

by alternating topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment twice daily Monday-

Thursday with clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily Friday-

Sunday, with notable improvement of the lesion within 3-4 weeks.

Immunotherapy was continued while his oral lichen planus was

treated.

Figure 2: Case 1- hematoxylin and eosin stain showing a lichenoid infiltrate with squamatization of the basal layer, consistent with lichen planus.

Discussion

Lichen planus is a CD8+ T-cell mediated autoimmune process

targeting basal keratinocytes causing apoptosis of epithelial cells and

resultant erosions and ulceration of mucocutaneous sites. The precise

mechanism of drug-induced lichenoid reactions is not completely

understood, but likely involves breaking the normal tolerance of

CD8+ lymphocytes for the epithelium. One signaling pathway which

may induce tolerance for the epithelium is through the interaction

of PD-1 with ligand B7-H1 [4]. Blockade of this interaction by

pembrolizumab and nivolumab likely tips the delicate balance of

tolerance allowing CD8+ lymphocytes to react against epithelial

cells. A number of other medications have been also associated

with oral lichenoid reactions, including angiotensin-converting

enzyme inhibitors, anticonvulsants, antiretrovirals, nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs, and more recently TNF-alpha and tyrosine

kinase inhibitors, though the pathogenesis is likely different than that

of checkpoint inhibitors [5,6].

Several cutaneous adverse effects of PD-1 inhibitors have been described, however, literature detailing oral mucosal toxicity and

optimal treatment strategies for this toxicity in patients treated with

checkpoint inhibitors for melanoma is more limited. Of lichenoid

eruptions [7,8], one study found mucosal involvement in only 1 of 14

patients [8]. Here we present two patients with advanced melanoma

who developed oral lichen planus within two months of treatment

with nivolumab. Both patients initially presented with isolated

oral involvement. In our first patient, the extensive nature of and

symptoms from her lichen planus led to temporary discontinuation

of nivolumab. The second patient did not require holding of

immunotherapy. Both patients improved with very high potency

topical steroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors, allowing the

first patient to resume nivolumab. Oral glucocorticoids or systemic

steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents were not used.

Conclusion

Our cases support considering oral lichen planus as a notable

cutaneous adverse event in patients receiving PD-1 inhibitor therapy

for the treatment of melanoma. Recognition of erosive lichen planus

early as an adverse event by both oncologists and dermatologists may

potentially avoid disruptions in immunotherapy with appropriate

treatment. Also, this experience suggests that topical therapy

alone either with high potency topical steroids or in combination

with tacrolimus ointment can provide a sustained response while

immunotherapy is continued. Of note, both patients had comorbidities

(DLBCL and psoriasis) suggestive of baseline immune dysregulation.

Future research investigating specific cutaneous adverse effects of

checkpoint inhibitors can yield more definitive answers about their

association with development of other immune-mediated adverse

reactions and implications for tumor response to therapy.