Journal of Clinical and Investigative Dermatology

Download PDF

Case Report

Primary Classic Kaposi’s Sarcoma Of Lymph Nodes In Ultrasound Resembling Lymphatic Metastases Of A Malignant Tumor And Successful First-Line Therapy With Ipilimumab

Kraehnke J*, Bogumil A, Grabbe S, Loquai C, Weidenthaler-Barth B and Tuettenberg A

Department of Dermatology, University Medical Center Mainz, Germany

*Address for Correspondence: Kraehnke J, Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Mainz, Langenbeckstrasse 1, 55131 Mainz, Germany, Tel: + 49 61 31 17 0; Fax: + 49 61 31 34 99; E-mail: juliane.kraehnke@unimedizin-mainz.de

Submission: 10 November, 2019

Accepted: 09 December, 2019

Published: 14 December 2019

Copyright: © 2019 Kraehnke J, et al. This is an open access article

distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original work is properly cited.

Abstract

We report on a 71-year-old patient with a classic, primary Kaposi’s sarcoma of

the lymph nodes. He presented with an inguinal lymphadenopathy. An ultrasound

examination showed suspicious lesions (oval lymph nodes with a single, round,

homogeneous hypoechoic structure with peripheral and diffuse vascularization),

yet typical sonomorphological criteria for lymph node metastases of a solid

malignant tumor such as melanoma (round lymph nodes with a round hypoechoic

area that often contains hyperechoic structures due to necrosis and a peripheral

vascularization) were not fully met. Nevertheless, due to the suspicious findings,

inguinal lymph nodes were extirpated. Histologically, there were formations of

a malignant tumor that led to the diagnosis of a nodal Kaposi’s sarcoma. Skin

examinations, HIV testing and imaging procedures presented no pathological

findings. A therapy with ipilimumab (3mg/kg every three weeks for four times)

was initiated, which resulted in durable tumor control.

Sonomorphological patterns for Kaposi’s sarcoma of the lymph nodes are

not yet defined. We report on this case to describe the specific sonomorphological

structures in our patient as a first step towards establishing sonomorphological

criteria for nodal Kaposi’s sarcoma. Furthermore, this is the first case to report on

a successful first-line therapy with the immune checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab in

classical Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Abbreviations

KS: Kaposi’s Sarcoma

Introduction

Kaposi‘s Sarcoma (KS) is a rare, malignant, angioproliferative,

multifocal systemic disease. Angioproliferative tumors can occur

in the skin, mucous membranes, lymph nodes and other organs.

It has been classified into four sub-types: classic (typically presents

in middle or old age in Mediterranean or eastern European men),

endemic (in indigenous Africans), iatrogenic (associated with

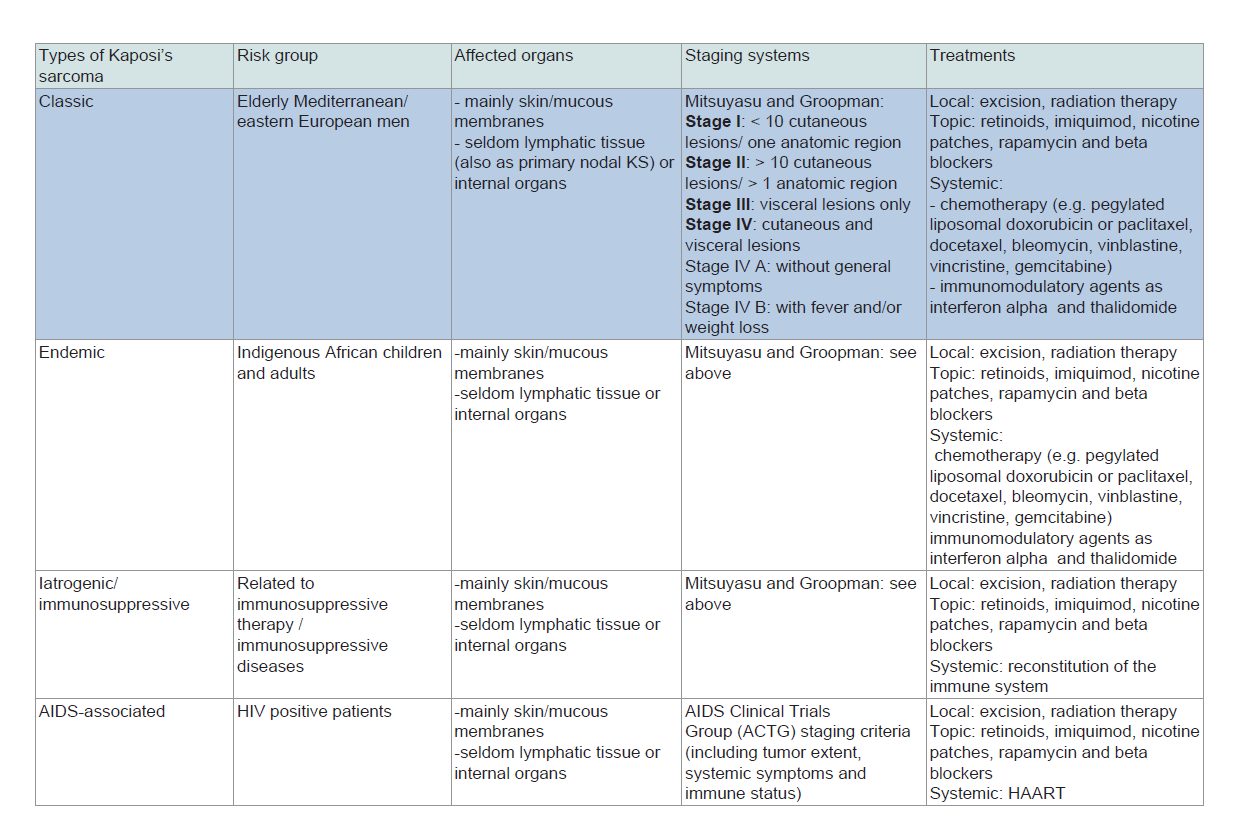

immunosuppressive therapy) and AIDS-associated KS (Table 1). In

about 90% of cases it is associated to human herpes virus-8 (HHV-

8), also known as KS-Associated Herpes Virus (KSHV) [1-3]. In this paper we will focus on classic KS since our patient suffered from a rare subtype of it: a primary nodal classic KS.

Usually, the suspected diagnosis is based upon the appearance

of skin lesions that vary from reddish blue to dark brown macules,

plaques or nodules. KS can be confirmed by histological examination

of the affected tissue, which typically shows evidence of angiogenesis

with thin-walled cleft-shaped vascular spaces, inflammation

(lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages) and spindle cell

proliferation [4-6]. In nodular lesions, tumors are more solid and

there are large fascicles of spindle-shaped endothelial cells with fewer

and more compact vascular slits. The mononuclear cellular infiltrate

decreases [4-6]. The histological diagnosis of nodal involvement is

complicated. At early stages there are similarities to reactive processes.

Only later in the course of the disease do spindle-shaped cells become

prominent [7]. Cells of the vascular structures and spindle cells stain

for endothelial markers such as CD31, CD34 and ERG as well as for

D2-40/Podoplanin. Immunohistochemical staining can be done to

detect the presence of HHV-8-LNA (latent nuclear antigen) within

the tumor cells or polymerase chain reaction can be performed

to detect HHV-8-DNA [6-8]. Kaposi sarcoma is the only vascular

tumor with positivity for HHV-8.

An important aspect during initial examination is the palpation

of lymph nodes to check for nodal involvement. Additionally, an

ultrasound of lymph nodes should be done to rule out nodal spreading.

To our best knowledge, there are no published sonomorphological

criteria of affected lymph nodes to date.

Further screening for distant organ involvement is dependent

on the subtype. In the case of asymptomatic patients with classic

KS, a radiographic evaluation is not normally needed due to the low

frequency of radiographically evident metastatic disease [9]. Patients

with gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. bleeding, diarrhea, proteinlosing

enteropathy, perforation) should undergo an endoscopy to

check for visceral mucosal involvement [9-11]. A staging system

for classic KS, proposed by Mitsuyasu and Groopman (1998), is

commonly used. The disease is grouped into stage I-IV based upon

disease distribution and clinical symptoms (Table 1). The course of the disease is dependent on the subtype. Classic

Kaposi’s sarcoma mostly has a chronic, indolent course and rarely

impacts survival. Sometimes, however, it has an acute onset with

rapid progression or a previously indolent disease can undergo

sudden worsening, causing significant morbidity and mortality [12-14]. In 5-20% of cases there is a mucosal and/or organic involvement

[15].

Table 1: Four variants of Kaposi’s sarcoma. We focus on classic Kaposi’s sarcoma (primarily nodal) in this paper.

Since there is no treatment to cure classic KS, the treatment

generally aims to achieve symptom palliation, improving function

and delaying or preventing progression [9]. Local therapy includes

excision even though local recurrences are common [15]. KS

is radiosensitive, so radiation therapy of cutaneous tumors is a

good option. Topical therapy with retinoids, imiquimod, nicotine

patches, rapamycin and beta blockers is only marginally efficient

[9]. Systemic treatments such as chemotherapy are used in cases

of rapid progression or multilocular disease. Standard treatment

includes pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or paclitaxel, docetaxel,

bleomycin, vinblastine, vincristine, gemcitabine, and etoposide

as second line [9,16,17]. However, chemotherapy is mostly

palliative. Immunomodulatory agents as interferon alpha and

immunomodulatory imide drugs (as thalidomide) have been used

in single cases with variable efficacy [16,18]. Recently published case

reports indicate that a therapy with anti-PD-1 agents might be a new

and successful therapy option [17,19,20].

Case Report

We report on a 71-year-old patient with a classic, primary

Kaposi’s sarcoma of the lymph nodes. Due to palpable inguinal

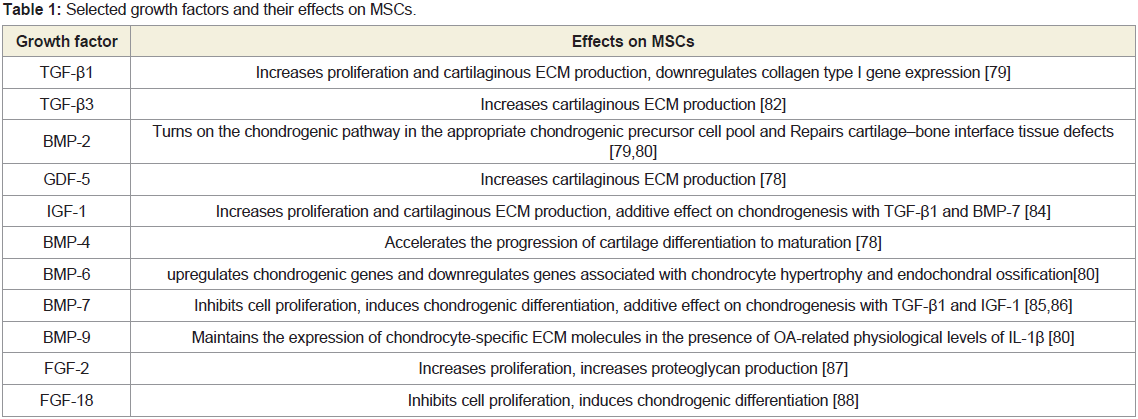

lymphadenopathy the patient presented at the clinic. On ultrasound,

lymph nodes presented suspicious being hyperechoic, oval shaped

with a single, round, homogeneous hypoechoic structure. The

hypoechoic structure showed a strong peripheral and diffuse

vascular pattern (Figure 1). These sonographic findings, albeit not

entirely typical, resembled those of lymph node metastases which

regularly present as hyperechoic, round shaped lymph nodes with

a round, nonhomogeneous hypoechoic area due to necrotic parts

of the metastases and a mainly peripheral vascularization (Figure 2). However, due to missing hyperechoic parts within the round,

hypoechoic structure and a strong diffuse vascularization, criteria

for lymph node metastases were only partially met. Furthermore, the

bilateral appearance of suspicious lymph nodes at the same time was

not impossible but uncommon for metastases. The presenting lymph

nodes seemed to be a mixture of metastases (due to the hypoechoic

structure with peripheral perfusion) and reactive lymph nodes (due

to the additional, strong diffuse perfusion). Due to these ultrasound

findings, imaging was extended. A CT showed soft-tissue masses,

unknown pulmonary lesions and suspect inguinal, iliac and axillary

lymph nodes. A bilateral extirpation of inguinal lymph nodes was

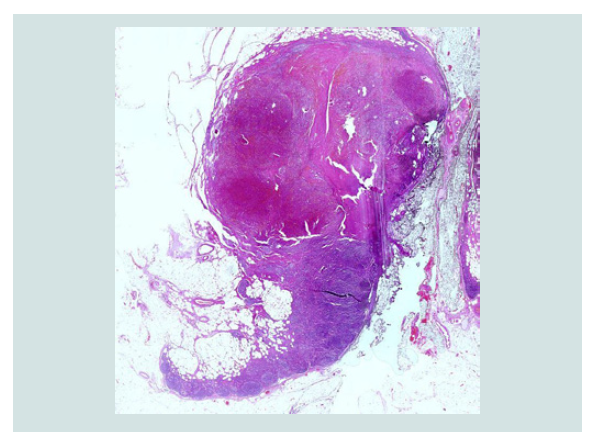

done. Histologically, there were formations of a malignant tumor

with siderosis and a mesenchymal proliferation of atypical spindleshaped

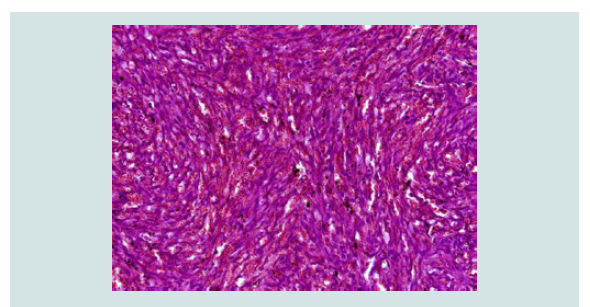

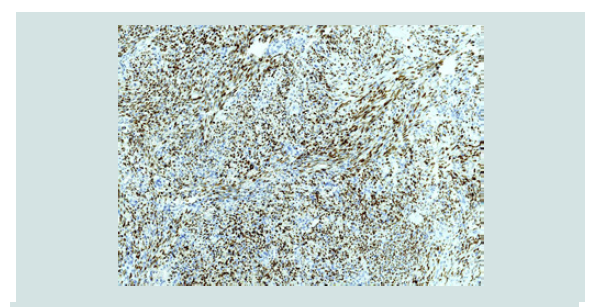

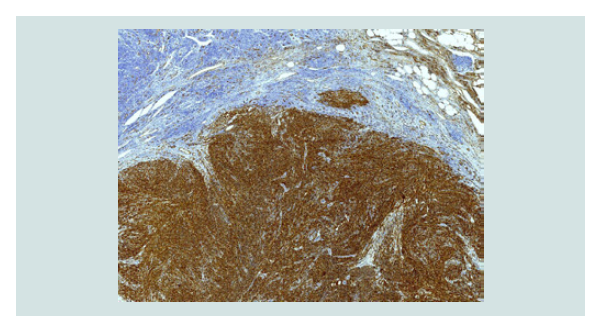

endothelial cells (Figure 3 and 4). The vascular markers CD34,

CD31, D2-40/Podoplanin as well as HHV8 showed a positive result

in the immunohistochemical staining (Figure 5 and 6). Histologically,

the diagnosis of a Kaposi’s sarcoma was rendered. Skin examinations,

HIV testing and blood tests that were done to rule out other organ

manifestations and immunodeficiency were without pathological

findings. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed due to

intermitting sickness. A gastritis was diagnosed but there was no

sign of mucosal tumor lesions. The patient also had not received

any immunosuppressive therapy. Therefore he was diagnosed with a

classic primary Kaposi’s sarcoma of the lymph nodes, an exceptionally

rare sub-type of classic KS since in most cases the diagnosis is

rendered due to skin lesions (i.e. not primarily nodal). A therapy with

ipilimumab (3mg/kg body weight, 4 cycles, every 3 weeks) was given

from June to August 2014. It was well tolerated except for a transient

hypophysitis as an immune-related adverse event. The last staging

was done in 2019 and showed ongoing regressive lymph nodes and

no other pathological findings. The soft tissue masses that were

apparent upon primary staging had also fully resolved after therapy

with ipilimumab. Thus no further therapy was initiated up to now.

Discussion

The main and so far undescribed aspects of this case report are

sonomorphological criteria in KS of the lymph nodes and the therapy

with the immune checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab in classic KS.

The use of ultrasound as a non-invasive imaging procedure

is performed in several skin diseases [21]. Nevertheless, there is

little data available regarding the ultrasound of KS lesions. Only

cutaneous lesions have been characterized a few times. Herein, the

authors describe partly contradictory sonomorphological patterns.

In 1993, Bogner et al. reported on skin lesions as hypoechoic,

with a homogeneous structure and well-defined outlines whereas

Cammarota described solid [22], nonhomogenous nodules with

poorly defined outlines [23]. In 2015, Carrascosa et al. described

details on the sonomorphological structure and vascularization of

cutaneous tumor lesions [24]. The pattern revealed by a B-mode

ultrasound was solid and hypoechoic and lesions were located in the dermis. Nodules were more homogeneous, with regular, well-defined

outlines, whereas plaques were less homogeneous with irregular

edges and less well-defined outlines [24]. The color doppler showed

intralesional vascularization that was prominent at the lower pole in

nodules and little or absent vascularization in plaques [24].

To our best knowledge, there are no published sonomorphological

criteria of affected lymph nodes in KS to date. As described, lymph

nodes in our patient presented hyperechoic, oval shaped with

a round, homogeneous hypoechoic structure with a peripheral

and diffuse vascular pattern in ultrasound (Figure 1). Therefore,

sonomorphological criteria overlap with those of e.g. melanoma

metastases. Nevertheless it was not possible to determine the tumor

entity by ultrasound only especially since there are no described

specific sonomorphological patterns of nodal involvement in KS.

Thus, it would be of great interest to include ultrasound sonography

in today’s routine staging for KS patients (i) in order to define in

more detail lymph node involvement in KS and (ii) to establish

sonomorphological criteria. This is desirable not only to improve

nodal diagnostics in patients with known KS but also to evaluate

therapeutic responses. Nevertheless, a histological examination of the

suspect tissue is important. This case demonstrates the importance of

combining ultrasound and histology to differentiate between various

malignancies. As described above, there is no curative systemic treatment of

advanced classic KS to date. Systemic chemotherapy with liposomal

doxorubicin, which is used in a progressive disease, achieves mostly

transient responses. A literature review of systemic treatment was

done by Régnier-Rosencher et al. in 2013, who described response

rates of various treatments from 43-100% but found that evidence

for efficacy of any particular therapy was of low quality and a specific

therapeutic strategy could not be recommended [16].

As described above, there is no curative systemic treatment of

advanced classic KS to date. Systemic chemotherapy with liposomal

doxorubicin, which is used in a progressive disease, achieves mostly

transient responses. A literature review of systemic treatment was

done by Régnier-Rosencher et al. in 2013, who described response

rates of various treatments from 43-100% but found that evidence

for efficacy of any particular therapy was of low quality and a specific

therapeutic strategy could not be recommended [16].

Immune checkpoint inhibition has been proven to be effective in

numerous malignancies, including virally mediated tumors such as

merkel-cell carcinoma (MCpV-associated) or Hodgkin‘s lymphoma

(EBV-associated) [25,26]. Oncovirus associated tumors, including

KS, seem to have a virally mediated increased expression of PD-L1

[25,26]. Contrary to these findings, higher-than-anticipated response

rates were also described in virus associated tumors with low PD-L1 expression, suggesting that also the presentation of viral antigens on

tumors may lead to an increased response rate to immunotherapy

[26].

Our patient is the first published case of a classic, primary nodal

Kaposi’s sarcoma that was treated with immunotherapy. The abovementioned

case reports describe patients either suffering from classic,

endemic or HIV-associated KS and receiving immunotherapy with

the anti-PD-1/PD-L1-agents pembrolizumab or nivolumab. Here, we

report on treatment with the CTLA-4-antibody ipilimumab that led

to a stable disease (regressive soft tissue masses and axillary, iliac and

inguinal lymph nodes). After a follow-up period of five years, we have

no sign of disease progression in our patient. Therefore, we conclude

that the therapy with ipilimumab was successful and led to a longterm

stable disease. Especially since we would have expected a disease

progression in this case of classic nodal KS (i.e. that is not limited to

the skin) without immunotherapy. The result supports the suggestion

that immunotherapy might be a promising therapy option in KS and

shows that it might even lead to a long-term stable diseases or even

complete response [17,19,25,26,31]. Furthermore, the use of immunotherapy

as first-line therapy has not been reported before. Since usually used

systemic therapies mostly show only a transient success, this would

be a new, life-saving option for patients with advanced KS. KS in

general often affects immunosuppressive patients. Chemotherapies

often additionally lead to myelosuppression as a side effect. Studies

with immune checkpoint inhibitors on a greater number of patients

are necessary to prove efficacy. The National Cancer Institute is

conducting a prospective study of combined ipililmumab and

nivolumab in patients with HIV associated cancers, including

Kaposi’s sarcoma (Clinical-Trials.gov, Identifier: NCT02408861);

final data will presumably be available at the end of 2020. The use of

immunotherapy as first-line therapy is desirable in order to replace

marginally effective chemotherapies.

Figure 3: HE staining at 40x magnification: Mesenchymal proliferation in the upper half of the lymph node.

Figure 4: HE staining at 400x magnification: Mesenchymal proliferation of atypical spindle-shaped endothelial cells forming vascular spaces; extravascular erythrocytes.

Conclusion

Sonomorphological criteria for KS of the lymph nodes are not

yet known. In our patient affected lymph nodes showed a round,

homogeneous hypoechoic structure with a peripheral and diffuse

vascular pattern in ultrasound leading to further diagnostics. Since

nodal involvement is rare, it is desirable to publish cases like this

one in order to develop a more profound and specific knowledge of

sonomorphological criteria for KS of the lymph nodes and thereby

improve and complement diagnostics as well as therapy evaluation.

Recently published data report on successful treatment with

pembrolizumab and nivolumab in single cases of endemic and HIV associated

KS when used as second- or third-line therapy [17-19].

Considering the knowledge of immunomodulation of KS [28-30], the

positive response rate to immune checkpoint blockage in other virus

associated immunomodulated tumors such as merkel-cell carcinoma

or Hodgkin’s lymphoma and the positive response to immune

checkpoint inhibitors in recently documented cases [17,19,25,26,31],

it is very likely that ipilimumab has resulted in an ongoing stable

disease in our patient. This case shows that immunotherapy seems

to be a promising option in patients with classic, primary nodal KS.

It supports the positive data about the efficacy of immunotherapy in

KS due to a first-time reported follow-up of five years. Furthermore

it indicates that anti-CTLA-4 therapy is a possible alternative if anti-PD-1 therapy is not applicable.