Journal of Clinical and Investigative Dermatology

Download PDF

Case Report

Pyodermatitis-Pyostomatitis Vegetans: A Cutaneous Clue for Crohn’s Disease

Tallman R1*, Beatty C1, Ghareeb E1, Gayam S2 and Zinn Z2

1Department of Dermatology, West Virginia University Medicine, USA

2Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, West Virginia

University Medicine, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Tallman R, Department of Dermatology, West Virginia University Medicine,

Morgantown, Medical Center Drive, HSC P.O. Box 9158, Morgantown, WV

26506-9158, Fax: 304-293-8055, Tel: 855-988-273; Email: rmtallman@mix.

wvu.edu

Submission: 30 July, 2021;

Accepted: 06 September, 2021;

Published: 10 September, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Tallman R, et al. This is an open access article

distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans is a neutrophilic dermatosis

that is classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease. It is

rare with less than 40 cases reported in the literature within the last 10

years. We discuss the case of a 30-year-old male who presented with

pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans and previously undiagnosed

Crohn’s disease. We aim to emphasize the importance of prompt

recognition of pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans order to

commence a thorough investigation of underlying inflammatory bowel

disease, and initiate appropriate therapy. Because no standardized

treatment regimens have been established, we also describe the

variability in treatment responses seen with pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis

vegetans with a review of the literature.

Abbreviations

Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans (PPV); Inflammatory

bowel disease (IBD); Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID);

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF); Gastrointestinal (GI); Ulcerative

colitis (UC)

Introduction

Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans (PPV) is a neutrophilic

dermatosis characteristically associated with underlying inflammatory

bowel syndrome (IBD) [1]. The first reported case of PPV

was in 1898 by Francois Hallopeau [2], and only 37 cases of PPV

were reported in the literature between 1979 and 2011 [3]. Diagnosis

can be challenging due to its resemblance to autoimmune blistering

disorders such as pemphigus vegetans, and infectious etiologies such

as Staphylococcus aureus and blastomycosis. Recognizing the signs

and symptoms of PPV is critical in order to prompt further work up

for IBD and begin appropriate management, especially considering

that responses to treatments can be variable among patients and often

require trial and error to maintain remission. Here, we report a case of

PPV that highlights the importance of prompt diagnosis, especially in

cases where underlying IBD has yet to be uncovered. We also perform

a literature review of treatment responses in patients with PPV.

Case Presentation

A 30-year-old Caucasian male with fever, hypotension, and

tachycardia was admitted for one-week history of abdominal pain,

diarrhea, rash, and concern for sepsis. Past medical history revealed

another recent admission for melena, diarrhea, and abdominal pain

which he had self-managed with 1 gram of ibuprofen per day. At

that time, EGD and colonoscopy revealed edematous and ulcerated

tissue with mucopurulent material. Biopsy revealed ulceration

and granulation tissue, which was diagnosed as non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced colitis. NSAIDs were

discontinued, however diarrhea and melena had since persisted Additional past medical history included intravenous drug abuse

managed with buprenorphine and naloxone, and recent unintentional 35-pound weight loss.

On admission, he was noted to have an elevated white blood cell

count of 12,800 /UL with 87% polymorphonuclear lymphocytes.

C-Reactive Protein was elevated at 189.5 mg/L (normal <8 mg/L).

Due to concern for sepsis secondary due to bacterial endocarditis,

vancomycin, cefepime, and metronidazole were started. Examination

of the rash revealed crusted vegetative plaques with a rim of pustules

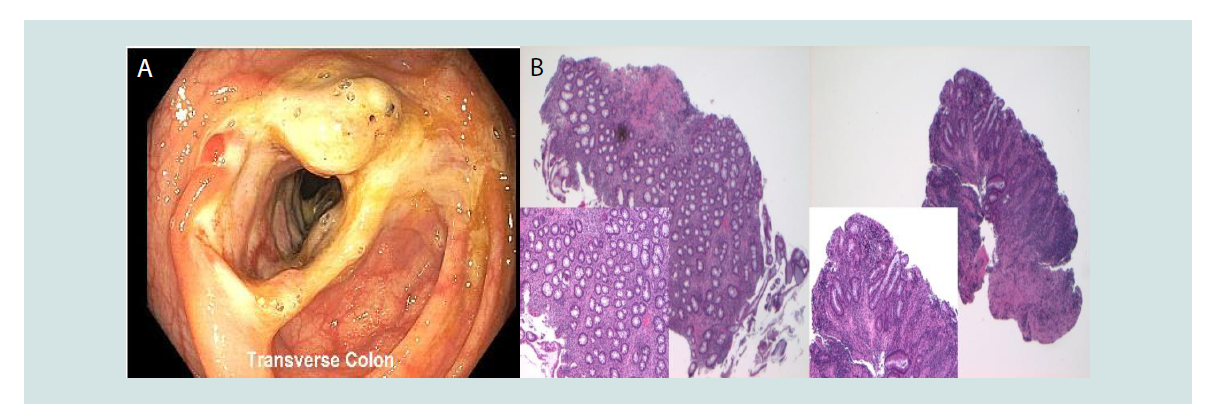

localized to the face, arms, and legs (Figure 1A,Figure 1B), and multiple

erosions on the hard palate. Dermatologic differential diagnosis

included deep fungal infection including blastomycosis, staphylococcal

infection, pemphigus vegetans, and PPV. Biopsyrevealed necrotic

epidermis, ulcerations, and neutrophilic infiltration (Figure 1C) with

negative direct immunofluorescence (DIF). Tissue cultures were

negative. Histologic diagnosis was compatible with a neutrophilic dermatosis including PPV.

Figure 1: Pyodermatitis vegetans lesions and histopathology. A. Multiple

erosions and crusts were observed on the face. B. On the extensor surfaces

were multiple erythematous papules and plaques with pustules studding the

borders and verrucous crust in the center of the lesions. C. Hematoxylin and

eosin at x 2, inset at x10; Punch biopsy from left arm showed an ulcerated

lesion with underlying neutrophilic abscesses and a neutrophilic interstitial

infiltrate. PAS, GMS, AFB Fite stains were all negative for microorganism.

Direct immunofluorescence was negative. Bacterial and fungal tissue cultures

were all negative for growth.

Given ongoing diarrhea, melena, and skin biopsy compatible with

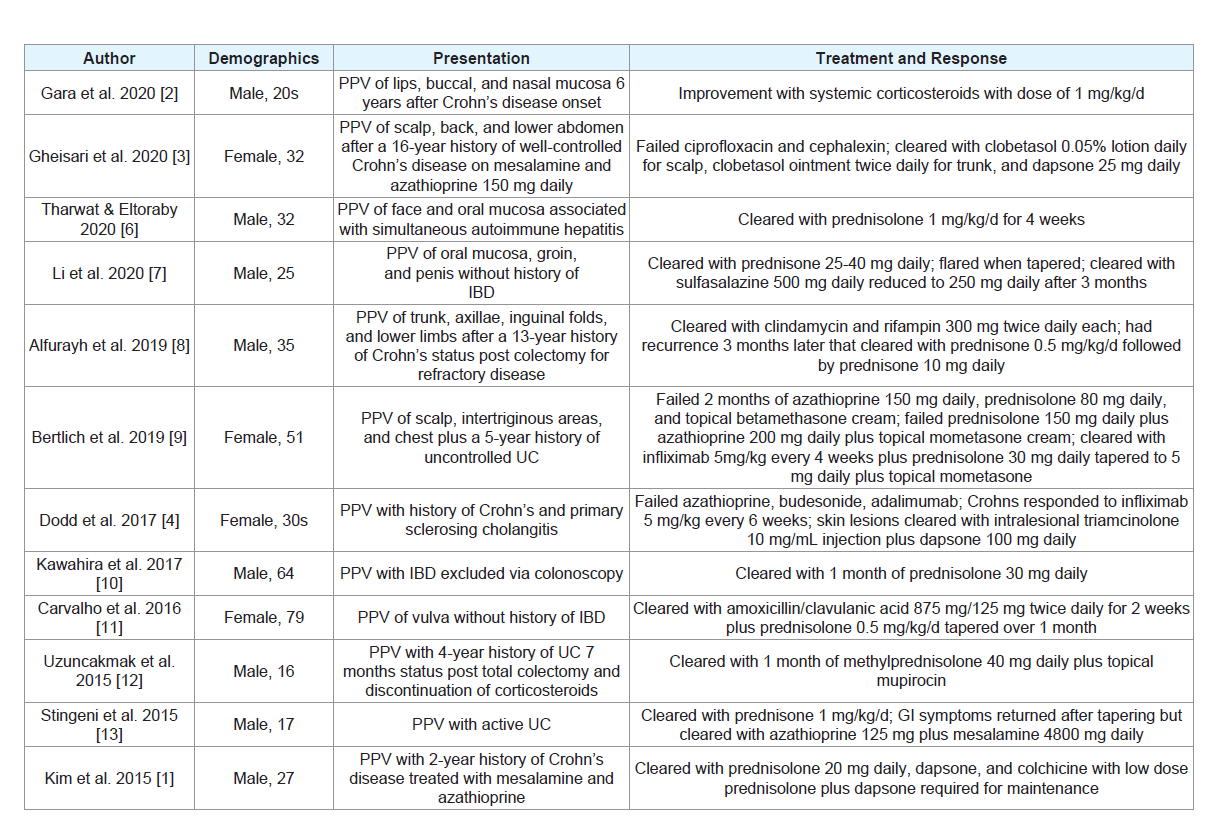

PPV, gastroenterology was consulted. Colonoscopy revealed multiple

strictures and large ulcers throughout the colon (Figure 2A). Biopsy of

the colonic lesions revealed focal chronic active colitis with ulceration

and granulation and no granulomas present (Figure 2B). IBD panel

was consistent with Crohn’s disease. Given his history and skin

biopsy results, it was suspected that the lesions were PPV secondary

to IBD. The patient was started on prednisone 40 mg daily with

significant improvement of skin and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms.

Vedolizumab infusions successfully controlled GI symptoms after

prednisone was tapered, however cutaneous manifestations of PPV

recurred. He was eventually switched to infliximab with successful

remission of both Crohn’s disease and PPV.

Figure 2: Inflammatory bowel disease. A. Colonoscopy revealed large ulcers found at the cecum, in the ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon,

and sigmoid colon. There was narrowing of the mucosa at several sites throughout the colon located near the ulcerations. B. Hematoxylin and eosin at x 4,insets at x10; On histology, there was focal active colitis with ulceration and granulation tissue. No granulomas were seen.

Discussion

PPV is a rare neutrophilic dermatosis that characteristically

presents with friable pustules of the oral cavity that form a “snailtrack”

pattern and papulopustular cutaneous lesions that give rise to

vegetating plaques [1]. PPV has a well-documented association with

IBD. Although it presents more often as a sequela of ulcerative colitis

(UC), it can be seen in Crohn’s disease as well, as in our patient [4].

Cases have also been reported with primary sclerosing cholangitis.

It is more common for patients to present with GI symptoms

prior to the onset of PPV, however skin lesions may appear first in

approximately 15% of cases [1]. Although classic PPV involves both

the mouth and the skin, involvement of both sites is not required to

render a diagnosis. The etiology of PPV remains uncertain, and males

between the ages of 20 and 50 are preferentially affected (3:1 male:

female ratio) [5].

PPV has characteristic histology including intraepithelial

and subepithelial splitting with neutrophilic and eosinophilic

microabscesses. It is important to distinguish PPV from auto-immune

blistering disorders, including the pemphigus vegetans subtype of

pemphigus vulgaris, IgA pemphigus, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita,

and dermatitis herpetiformis. Unlike these blistering disorders, DIF

is negative in PPV. Additional considerations include cutaneous

infections such as blastomycosis-like pyoderma due to S.aureus, and

endemic dimorphic fungal infections such as blastomycosis, which

can be differentiated by positive tissue cultures. Finally, clinical

findings of oral ulcers and documented IBD also support the diagnosis

of PPV [1,3]. Our patient exhibited characteristic histology of PPV

with negative DIF, negative bacterial and fungal tissue cultures, and

presence of oral ulcers diffusely on the hard palate with new diagnosis

of underlying IBD.

There is no standardized treatment for PPV, and responses

to different therapies are extremely variable among patients. To

illustrate this, we performed a review of case reports and case series

of PPV since 2015 in PubMed detailing patient responses to varying

treatment regimens, which is summarized in Table 1. Although

there is no standard algorithm for management, corticosteroids are

considered efficacious first line therapy. They are used as systemic,

intralesional, and topical treatments depending on disease severity.

All the cases reviewed that used corticosteroids achieved clearance,

however relapse was common when tapering [1-4,6-13]. Other

systemic treatments for PPV include dapsone, azithromycin cyclosporine, methotrexate, and infliximab, although varying efficacy has been reported with these options. Other topical treatments

include tacrolimus, mupirocin, and antiseptic mouth washes for oral

involvement.

Often the clinical courses of PPV and IBD are parallel [1], and

successful management of the underlying IBD typically results in

resolution of PPV [2]. However, there have also been cases in which

PPV develops and persists despite well controlled IBD [1,3,4]. Our

patient was started on vedolizumab initially for Crohn’s disease due

to preference over infliximab, however he was eventually switched

to infliximab after his skin manifestations continued to flare. Both

his skin and GI symptoms have been well controlled with infliximab

infusions. Previous reports have shown successful responses of both

cutaneous and GI symptoms to infliximab [14], whereas vedolizumab

has shown less efficacy in treating cutaneous manifestations of IBD

[15].

Conclusions

In summary, we present a case of PPV that posed a diagnostic

challenge, given both the patient’s risk factors for infectious cause

and unknown underlying Crohn’s disease. Our case demonstrates

characteristic clinical and histological features of PPV and highlights

the necessity to recognize this condition to screen for underlying

IBD. A review of the literature revealed the majority of cases clear

with corticosteroid treatment, however relapse is common once

discontinued. Although PPV has been shown to resolve with

management of IBD, this was inconsistent among the reviewed

cases and with our patient as well. Responses to other treatments for

maintenance of PPV is variable and often requires trial and error to

achieve remission.