Journal of Clinical and Investigative Dermatology

Download PDF

Case Report

Mycosis Fungoides Presenting After Dupilumab Therapy: Case Report and Systematic Review

Visconti M1, Teklehaimanot F2, Tan V2 and Fivenson D1,3*

1Department of Dermatology, St Joseph Mercy Hospital Ann Arbor,

Ypsilanti, Michigan

2Michigan State School of Osteopathic Medicine, East Lansing, Michigan

3Fivenson Dermatology, 3200 W Liberty Rd, Suite C5, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Submission: 24 March, 2023

Accepted: 04 April, 2023

Published: 02 May, 2023

*Address for Correspondence

Fivenson D, Fivenson Dermatology, 3200 W Liberty Rd, Suite C5,

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48103; USA; Phone: 734-222-9630; E-mail:

dfivenson@fivensondermatology.com

Copyright: © 2023 Visconti M, et al. This is an open access article

distributed under the Creative Commons Attri-bution License,

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in

any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis; Cutaneous T cell Lymphoma;

Cytokine; Mycosis Fungoides; Cutaneous T cell Lymphoma; IL-13, IL-4;

IL-13Rα1 and IL-13Rα2

Abstract

Introduction: Several reports have been made associating

dupilumab therapy for atopic dermatitis (AD) with the development of

mycosis fungoides (MF) and other cutaneous T cell lymphomas (CTCL)

Methods: A new case report and systematic review were

conducted to identify reports of MF/CTCL after minimum 6 weeks of

dupilumab therapy between January 2021 and March 2023.

Results: 28 patients from 18 publications (including our case) were

identified, averaging 17.4 years of AD duration with 18.5 weeks of

dupilumab therapy prior to MF/CTCL diagnosis. MF/CTCL presented

as 6 stage I, 4 stage II, 3 stage III, 4 stage IV, 3 Sezary syndrome, 6

large cell transformation, 2 peripheral T cell lymphoma (PTCL) and 1

with coexisting Hodgkin’s lymphoma. There were 13 females, 15 males,

and included 2 African-Americans, 4 Asians, and 22 Caucasians. 11

patients had initial improvement on dupilumab.

Conclusion: Clinical unmasking of MF/CTCL or de novo

lymphomagenesis as the mechanism in these patients is unknown.

Increased IL-13 and/or inhibition of reactive T cells through IL-4/IL-

13 blockade are possible mechanisms of action. Awareness of this

phenomenon during AD treatment and close follow-up and biopsy of

non-responders or those who develop new morphologies is important.

Introduction

Mycosis Fungoides (MF) is the most common subtype of

cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) [1,2]. The disease is characterized

by patches, plaques, and tumors that can be intensely pruritic and

present in various sizes, shapes, and colors [2]. The cutaneous

findings of MF can mimic other common cutaneous diseases such

as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and parapsoriasis, making diagnosis

challenging, and often requiring serial biopsies [3].

While the etiology of MF remains unknown, various hypotheses

have been proposed which include genetic, environmental, infectious,

and autoimmune involvement [4,5]. Recently, there have been several

reports of MF diagnosed after the initiation of dupilumab therapy for

atopic dermatitis (AD) or other eczematous conditions [6-23]. In this

report, we present another case of AD developing stage IIB MF in the

ensuing months after starting dupilumab and a systematic review of

all published cases of this association, as well as the hypotheses for

how this transition may occur.

Methods

A systematic English language literature review using PubMed

and Google Scholar between January 2021 and March 2023, with

key words of (mycosis fungoides and dupilumab, cutaneous T cell

lymphoma and dupilumab, as well as descriptors of transformation,

progression and misdiagnosis) was conducted to identify reports of

the diagnosis of MF/CTCL in association with dupilumab treatment.

All relevant reports had full text review by the senior author. Inclusion

criteria included patients who were diagnosed with MF/CTCL

following treatment with dupilumab, any preexisting dermatosis

was included. Exclusion criteria included reports without histologic

confirmation of MF/CTCL and those with diagnosis after less than 3

doses (6 weeks of standard initial therapy) of dupilumab therapy. This

was done to exclude cases that could have been benign dermatoses

that were temporarily given dupilumab while diagnostic workup for

MF/CTCL was ongoing, as biologic transformation seems unlikely

in such a short time frame. Preexisting MF/CTCL reports that were

exposed to dupilumab were also excluded.

Data extracted included age, sex, AD duration, initial clinical and

histologic features, prior therapies, duration of dupilumab treatment,

MF/CTCL clinical presentation, MF histology, immunophenotyping,

TCR gene rearrangement, TNMB staging, and subsequent therapy.

Results

Case 1: A 77-year-old male with a 10-year history of AD,

presented to our clinic with worsening pruritus on the upper

trunk and buttocks. Skin biopsies previously had shown spongiotic

dermatitis with eosinophilic infiltrates. Prior treatments had included

narrow-band ultraviolet light phototherapy (NBUVB), high-potency

topical steroids (TS), and 17 weeks of dupilumab. Examination

revealed extensive annular, atrophic, erythematous, scaling, patches

and plaques which the patient noted had thickened since starting

dupilumab. Repeat skin biopsy revealed an acanthotic epidermis with

an atypical epidermotropic infiltrate of hyperchromatic-lymphocytes.

Immunophenotyping showed a predominant T cell infiltrate

that was CD2+, CD4+, CD1a-, CD3-, CD5-, CD8-, CD7-. T cell

receptor (TCR) gamma and beta gene rearrangements were positive.

Peripheral blood immunophenotyping, TCR, and PET scan revealed

no systemic involvement. The patient discontinued dupilumab and

started psoralen plus ultraviolet A photochemotherapy (PUVA)

treatments twice weekly. Improvement in disease extent and lesion

thickness was noted within 8 weeks and after 30 treatments the

patient was almost clear.

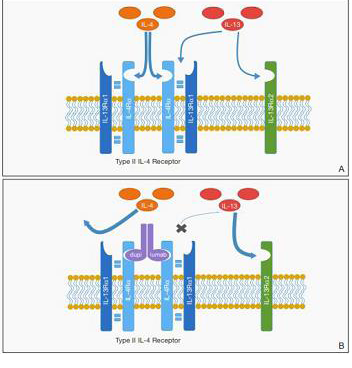

Figure 1: Proposed mechanism for promotion of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

(CTCL) by dupilumab. A, IL-4 and IL-13 bind to the type II IL-4 receptor (IL-

4R). IL-13 also may bind at a distinct IL-13 receptor α2 (IL-13Rα2) site. B,

Following blockade of the type II IL-4R, reduced binding at IL-4R may result

in increased free IL-13 available for binding at the IL-13Rα2 site, which may

have a role in promoting CTCL proliferation. Reprinted with permission from

Hollins LC, et al, from Cutis.2020 August; 106: E8-E11. ©2020, Frontline

Medical Communications Inc.

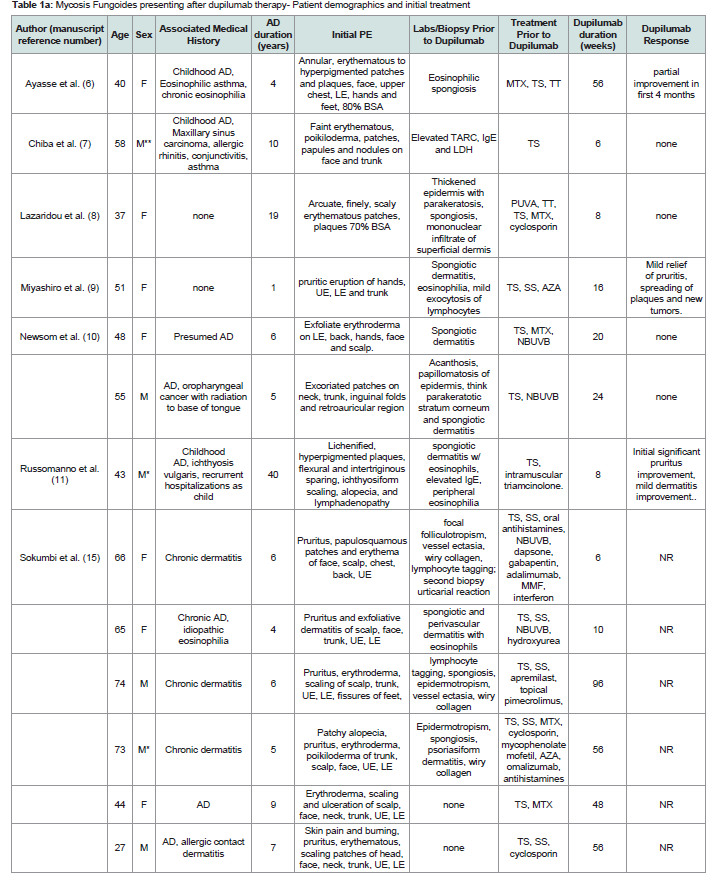

Patient demographics, clinical and histology before dupilumab therapy:

19 studies were included, totaling 28 patients included in our

series. 9 patients excluded after review of the publications due to

insufficient length of dupilumab exposure (n=3) or its use reported in

preexisting MF/CTCL subjects in the study (n=6)The demographics of the patients included in this study are

summarized in [Table 1]. There were 15 males and 13 females. There

were 22 Caucasian, 2 African American and 4 Asians with an age range

of 27-77 years and a mean of 55 years. Duration of disease ranged

from 1 to 58 years, mean= 17.4. Patients starting dupilumab therapy

had a history of AD or presumed AD although several did not report

skin biopsy findings pretreatment [Table 1] , with associated diseases

including IgE mediated disorders (asthma, allergic rhinitis, idiopathic

eosinophilia, and conjunctivitis) (n=5), and single cases each, allergic

contact dermatitis, maxillary sinus carcinoma, oropharyngeal cancer,

and ichthyosis vulgaris.

Clinical presentation and distribution of the skin eruption was

widespread with reports of extensive disease (>70% body surface

area-BSA) or exfoliative erythroderma prior to starting dupilumab

in 18/23 cases that described disease extent prior to dupilumab

therapy. Pruritus was dominant in most cases with morphologies

described including prototypical AD (lichenified and excoriated

flexural patches and plaques), urticarial, palmoplantar dermatitis,

ichthyosiform xerosis, blepharitis and conjunctivitis.

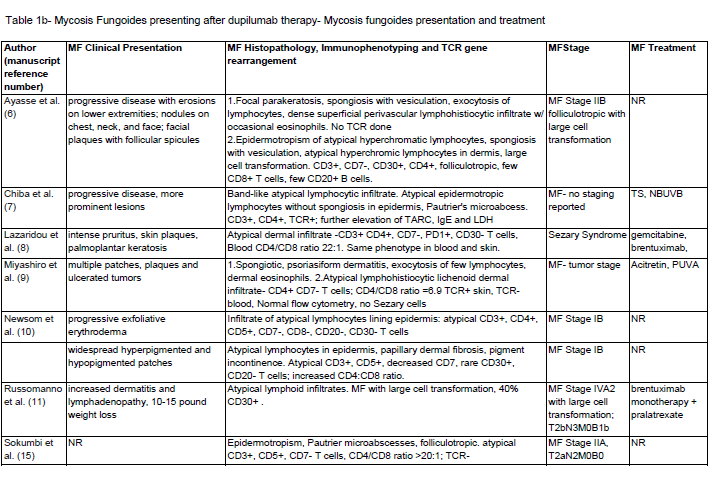

Post-dupilumab clinical and histologic findings:

Clinical and histologic features that changed after dupilumab

treatment are also summarized in [Table 1] . The mean duration of

therapy was 18.5 weeks prior to MF/CTCL diagnosis. There were 2

reports of complete clearing and 8 of partial improvement of symptoms

while on dupilumab. But eventual worsening and associated with

the progression of lesions occurred in all reports. Some describe the

development of secondary lesions including thicker plaques, nodules,

erosions, exfoliative erythroderma, and ulcerating tumors.The majority of patients had CD3+, CD4+, CD7-, CD8- atypical

infiltrates with increased CD4:CD8 ratio with one case of CD8+

MF. Including the case above, there were 28 cases of MF/CTCL with

staging including: 6 stage I, 4 stage II, 3 stage III, 4 stage IV, 3 Sezary

syndrome, 6 large cell lymphoma (LCL) transformation, 2 PTCL and

1 with coexisting Hodgkin’s lymphoma. TCR was positive in 6/14 and

not reported in 14 cases.

Discussion

In 2017, Dupilumab became FDA approved to treat adults

with moderate/severe AD [25]. Dupilumab is a monoclonal IgG4

antibody that blocks the IL4 receptor alpha chain in the shared IL-4/

IL-13 receptor, leading to a decrease in TH2 cell cytokine-mediated

signal transduction [26-28]. Common side effects include injection

site reactions, headache, myalgia and blepharoconjunctivitis [28,29].

In this review, we have summarized a total of 28 cases (including

1 new case from the senior author’s practice) that have a temporal

association with the development of MF/CTCL, a mean time of

18.5 weeks on dupilumab therapy. Park et al and Schaefer et al have

recently reviewed MF/CTCL in association with dupilumab or other

biologic therapies [30,31], but these series did not apply stringent

criteria of at least 6 weeks of dupilumab exposure as we have to

underscore meaningful exposure to this agent in association with the

evolution of MF/CTCL.

Heymann’s commentary highlighted new reports of dupilumab

in prurigo nodularis and bullous pemphigoid that appeared in the

same journal issue as that of Espinosa et al [32], who reported 3

cases of AD developing MF while on dupilumab as well as 3 cases of

MF who received it as adjuvant therapy for itching [12]. No adverse

events were reported in the studies involving PN or BP, although the

patients with AD who eventually were diagnosed with CTCL had

worsening symptoms after various initial periods of improvement.

In the same issue, the editor summarized several cases of MF after

dupilumab treatment and commented on the role of IL-13 excess in

lymphomas and the complex interplay of TH1/TH2 cell responses in

the microenvironments of these diseases by paraphrasing the adage

‘if it’s dry, wet it and if it’s wet, dry it’ as not being the same as ‘if it is

upregulated, downregulate it’ [33]

MF is a malignancy of TH2 T cells, and it is unclear how inhibition

of the IL4/IL13 receptor might facilitate the proliferation of these cells.

It is possible that blocking IL-4/IL-13 signaling on normal/reactive

lymphocytes allows pre-existing small numbers of transformed T cells

to proliferate. This is analogous to prior reports of progressive MF/

CTCL in response to other immunosuppressive regimens, including

classical chemotherapy and calcineurin inhibitors [34]

Table 1a: Mycosis Fungoides presenting after dupilumab therapy- Patient demographics and initial treatment

Abbreviations: MF- mycosis fungoides, CTCL- cutaneous T cell lymphoma, UE- upper extremities, LE- lower extremities, TS- topical steroids, SS- systemic steroids,, TT- topical tacrolimus, NBUVB- narrow band ultraviolet B, PUVA- psoralen plus ultraviolet A, TCR- T cell receptor gene rearrangement, AZA- azathioprine, MTXmethotrexate,

ALK- anaplastic lymphoma kinase, TIA-1- T cell intracellular antigen 1, PTCL- peripheral T cell lymphoma, MMF- mycophenolate mofetil, BSA- body surface area, NR- not reported. *= African american, **Asian

Table 1b: Mycosis Fungoides presenting after dupilumab therapy- Mycosis fungoides presentation and treatment

Abbreviations: MF- mycosis fungoides, CTCL- cutaneous T cell lymphoma, UE- upper extremities, LE- lower extremities, TS- topical steroids, SS- systemic steroids,, TT- topical tacrolimus, NBUVB- narrow band ultraviolet B, PUVA- psoralen plus ultraviolet A, TCR- T cell receptor gene rearrangement, AZA- azathioprine, MTXmethotrexate, ALK- anaplastic lymphoma kinase, TIA-1- T cell intracellular antigen 1, PTCL- peripheral T cell lymphoma, MMF- mycophenolate mofetil, BSA- body surface area, NR- not reported. *= African american, **Asian

It is not possible to tell if any/all these patients had preexisting

MF/CTCL or whether this was de novo transformation into a

malignancy. Due to the relatively short time frame for MF diagnosis,

we review here (median time after dupilumab therapy was 8 months)

and the overall rarity of this presentation compared to the extensive

use of dupilumab in AD, we suspect that atypical T cells were

already existing in many of these patients’ skin prior to dupilumab

therapy. Proliferative T cell neoplasia may have been thus allowed

to progress, much the same as how the gradual diminution of host

immunity with the advancing stage of CTCL has been classically

described to promote progressive disease over time [35]. Additional

hypotheses include the upregulation of IL-13Rα2, a decoy receptor

involved in atopic dermatitis but not blocked by dupilumab [36].

IL-13Rα2 binding by the excess IL-13 could have autocrine effects in

the microenvironment that may further stimulate the growth of the

malignant cells as proposed by Wadele et al [37] and Geskin et al [38]

and previously proposed in the figure published by Hollis et al [13].

Another possible mechanism is that malignant T cells may no longer

bind dupilumab with the same efficacy of normal T cells [37-39].

Conclusion

All these mechanisms remain unproven but have a permissive

effect of dupilumab in mycosis fungoides evolution. Dupilumab has

been a very effective new agent in our armamentarium and these

cases are best seen as a cautionary tale that clinicians pay attention

to the patient’s history and presenting symptoms when initiating this

therapy and have a low threshold for biopsy of any lesions that are not

classic. Atypical/poor responders should be closely followed up and

repeat biopsies considered detecting any unmasked cases of CTCL as

early in therapy as possible.