Journal of Emergency Medicine & Critical Care

Download PDF

Review Article

Thinking about Inking; Medical Alert Tattoos and Practical Implications of Their Use for Providers and Patients

Brito AMP1-3*

1University College Cork, National University of Ireland School of Medicine.

Brookfield Health Sciences Complex, College Rd, Cork, T12 AK54, Ireland

2Queen’s Medical Center, 1301 Punchbowl Street, Honolulu HI 96813

3Oregon Health and Science University, 3181 Sam Jackson Rd, Portland OR

97239

Address for Correspondence:

Brito AMP, Queen’s Medical Center, 1301 Punchbowl Street,

Honolulu HI 96813; E-mail: a.brito.26@gmail.com

Submission: 20 September 2022

Accepted: 10 October 2022

Published: 13 October 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Brito AMP. This is an open access article distributed

under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted

use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work

is properly cited.

Abstract

Objective: Medical alert tattoos (MATs) are under-recognized and

under-studied. The information contained in tattoos may be useful

for guiding patient management in emergent presentations such as

trauma and critical illness when the patient is unable to communicate.

However, use of MATs is fraught with medico-legal complexity as well

as reliability and safety concerns. This study aims to examine patterns

of use and develop recommendations for patients and providers.

Methods: An online survey was created for health care providers,

patients and tattoo artists regarding incidence, background

motivation, content of tattoos as well as providers’ experience with

and recommendations for their use. A literature review was performed

to examine the available evidence presented in previously published

case reports as well as historical, clinical, and ethical reviews.

Results: Allergies and chronic medical conditions were commonly

seen. Of the providers who had encountered a MAT 39% reported

that it had influenced patient management. Literature review showed

wide heterogeneity in the use of MATs by patients and providers.

Conclusion: Whether or not MATs are a good idea, patients

are using them to communicate medical information. Health care

providers should be aware of their use and the complex issues around

interpreting the information they contain.

Keywords

Tattoos; Health information; Advance directives; Emergency

care; Medical alert

Introduction

Tattooing: Tattooing is a popular format for body modification

that involves the deposition of pigments into the skin to create

permanent markings. Contemporary studies indicate that in the USA

and Europe 1/5 to ¼ of the population has at least one tattoo [1,2].

However, tattooing is far from a new concept. The earliest known

tattoo is about 5200 years old [3], and in ancient Egypt tattooing

was relatively common practice [4]. In the context of contemporary

western society, tattooing was popularized in Britain and America

during military campaigns with the prevalence of tattoos reaching as

high as 65% in members of the US Navy in World War II [5-8].

Tattoos in Medicine: Tattoos have been used in a variety of ways

in medicine. The presence of inked dots and lines over the lower back

and spine in a late Neolithic mummy in a pattern corresponding to

acupuncture sites has been theorized to indicate a possible therapeutic

intent of the tattoos themselves3, and in some parts of contemporary

West Africa tattoos are placed on the forehead to treat epilepsy or

hands and feet to treat peripheral neuropathy [9].

Tattoos may be used to cover scars or recreate the appearance of

normal anatomic structures such as nipple tattoos after mastectomy

or corneal iris tattoos in leucomata [10-14]. They may mark the site of

a colonoscopic biopsy allowing localization during surgical resection or the site of radiation therapy to ensure consistent localization

[15,16]. Ongoing studies are evaluating color changing tattoos as

continuous monitors of blood glucose for diabetics which may

facilitate recognition of hypoglycemic events [17].

Tattoos as a media for medical information have been in use

for more than half of the last century. Large scale blood type tattoo

programs were used in Germany in World War II for service

members, and US civilian programs during the cold war resulted in

thousands of adults and children receiving blood type tattoos [18].

In the military context medical and identifying tattoos with enlisted

person’s name, blood type, religion and other information are usually

placed on the flank [19]. These are sometimes referred to as “meat

tags” as part of their intent is to increase the chance of remains being

identified and sent home in the case of death in combat, as the torso is

frequently the largest portion of the body left intact after high energy

trauma.

The use of medical alert tattoos raises questions of safety,

accuracy, social concerns, and ethical/medico legal concerns. While

there are several case reports, small survey studies and popular media

articles there is need for a broader systematic approach to studying

these tattoos and the implications of their use for both patients and

medical professionals.

Methods

Review of case reports: A search was performed using the

PubMed database with search terms “medical alert tattoo”, “medical

tattoo”, “Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) tattoo”, “tattoo” and results

filtered for relevance. 14 studies were identified with specific case

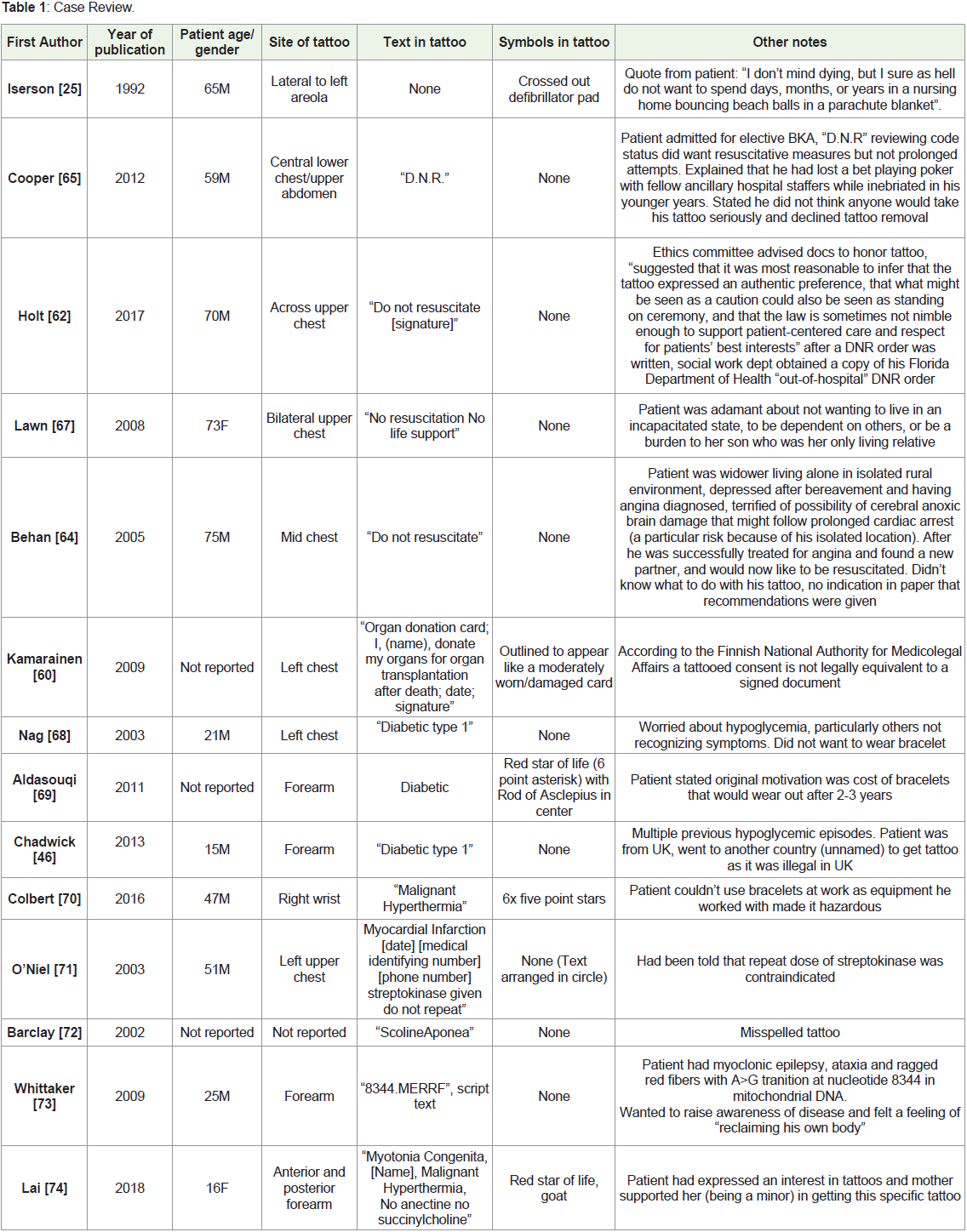

reports. The results are summarized in Table 1. Popular media articles

were not used for case review.

Survey: A survey was created with questions targeted to tattoo

artists, health care professionals, and patients with chronic medical

conditions with and without medical alert tattoos. Surveys were

designed to obtain maximal demographic and content information

as well as examine motivations and applications of these tattoos.

The tattoo artist survey focused on incidence of medical alert tattoos, content, and technical aspects of tattooing and tattoo aging.

The health care professional survey focused on experiences with

medical alert tattoos in practice as well as recommendations for use.

The patient survey focused on demographic information, medical

history as it pertains to tattoo content, text and symbol content of

tattoos, tattoo placement, motivations and attitudes about tattoos

as well as receptiveness to recommendations. The study and surveys

were reviewed and approved by the ethics board of the University

College Cork. The survey link was made available on a social media

site (Facebook) created for the purpose of this study with study

aims, safety and ethical information available. This was distributed

through a combination of sharing on other social media sites such

as tattoo artist interest groups, various medical groups, and health

care associated sites as well as through email between 2014 and

2019. There were zero responses from these methods for the tattoo

artist arm so surveys were printed and brought in person to tattoo

shops at various locations in the United States of America, Canada,

and Ireland. This allowed additional conversation about answers to

survey questions as well as various technical explanations of tattoo

techniques and limitations. Only two artists refused to complete the

survey when approached in person. The overall response rate was not

available as it was not possible to accurately quantify total reach given

the methods of distribution.

Results

Surveys: Survey respondents numbered 10 for tattoo artists, 14

for patients with medical alert tattoos, 20 for patients with chronic

health conditions but no medical alert tattoo, and 54 for health care

professionals.

Tattoo artists: 90% of tattoo artists surveyed had done a medical

alert tattoo. Artists surveyed had a range of 5-30 years’ experience

with a mean of 12 years. The number of tattoos done ranged from 0-50

with a mean of 10 and median 9. In terms of technical considerations

for tattooing, tattoo artists uniformly advocated simple text relative

to any form of cursive or fancy font as having greater longevity. Most

artists felt that the size of lettering to have good long-term legibility

would be around 1 inch or 2.5 cm although this would vary based on

experience and technique (for example, single needle vs multi needle).

Patients with medical alert tattoos: 50% of patients with medical

alert tattoos surveyed were between the ages of 26-35. Almost all had

gotten their medical tattoo within the 5 years prior to responding to

the survey. 93% had previously used other media such as jewelry or

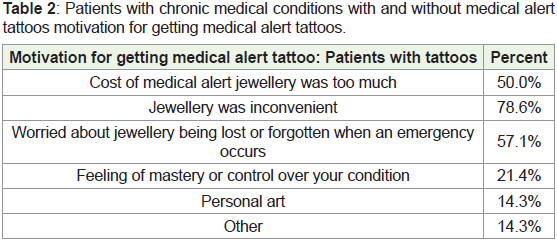

cards to keep their medical information on their person. Motivations

for getting a medical alert are summarized in the first portion of

Table 2. These patients had a range of 1-12 tattoos in total with 40%

having only one tattoo (the medical alert tattoo). Of those patients

with multiple tattoos, 22% had their medical alert tattoo placed near

other tattoos. 93% said that they would have considered following recommendations on content, design and placement for medical

alert tattoos provided by health care professionals if they had been

available at the time they got their tattoo.

Table 2: Patients with chronic medical conditions with and without medical alert

tattoos motivation for getting medical alert tattoos.

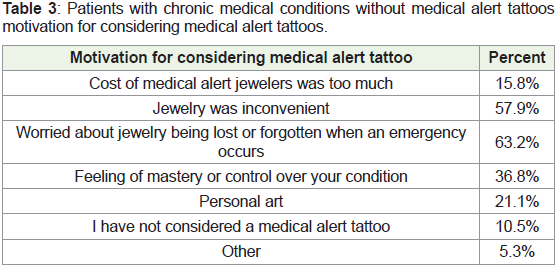

Patients with chronic health conditions without medical alert tattoos: 50% of patients in this category were between the ages of 36-

50. 90% have considered getting a medical alert tattoo. Motivations

for considering this option are listed in the second portion of Table 3.

90% would consider following recommendations for content, design

and placement if such recommendations were available from health

care professionals.

Table 3: Patients with chronic medical conditions without medical alert tattoos

motivation for considering medical alert tattoos.

Health Care Professionals: 85% of health care professionals

surveyed were either paramedics/EMTs or physicians, the remaining

15% identified as nurses, NPs, PAs or other. All respondents were

involved in direct patient care. 33% had seen a patient with a medical

alert tattoo and of those 39% reported that their treatment of a patient

had at some point been influenced by the information in the tattoo. All

of these instances were in emergent situations. 83% of those surveyed

would support a patient considering a medical alert tattoo and 89%

would consider providing recommendations based on health care

professional guidance to patients considering a medical alert tattoo.

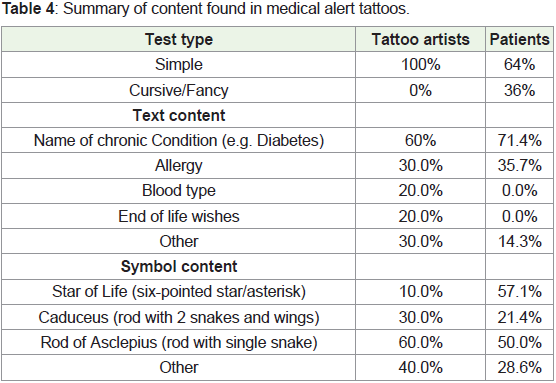

Content: Content of tattoos is summarized in Table 4. Text

content included in the “other” category generally referred to medical

history that did not fit into general chronic medical conditions

(for example, history of splenectomy, prior administration of

streptokinase). Symbols included in the “other” category ranged

widely and notably included blue circles and I>^v, (both of which

are representative of diabetes) as well as cartoon characters, 5 pointed

stars, syringes, skull and crossbones.

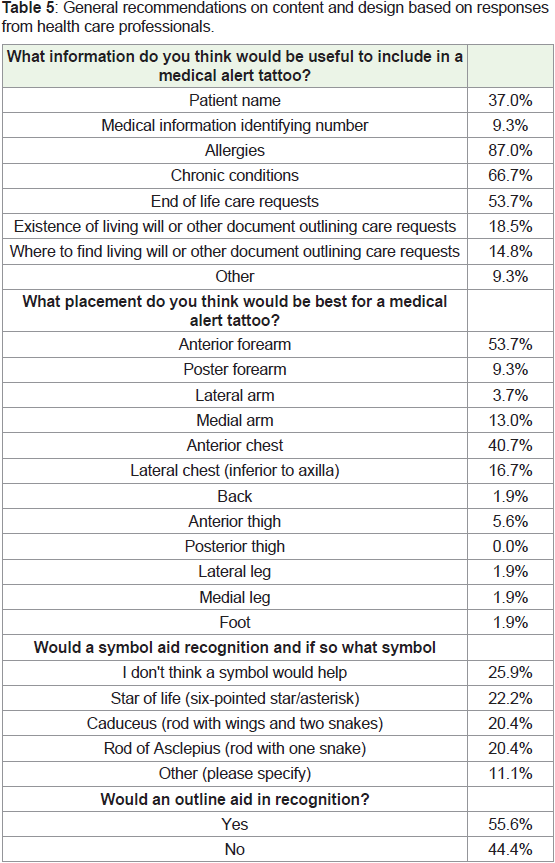

Recommendations: Health care providers were asked about their

recommendations for content and placement to make medical alert

tattoos more recognizable and useful to the patient. Responses are

summarized in Table 5.

Discussion

Incidence/Prevalence: The incidence and prevalence of medical

alert tattoos is very difficult to estimate. The usual creators of medical

alert tattoos, tattoo artists, are theoretically a good source of data

but this proved very difficult to obtain. Prevalence estimates are also

difficult as there is likely response bias, particularly with social media.

However, when searching popular media articles and image search

engines it is clear that tattoos are being used by many patients to

convey medical information. Given their widespread use by patients

it is important that health care professionals are aware of this practice

and be trained in their recognition and interpretation in situations

where a patient cannot communicate their medical information.

Content: In terms of tattoo subject matter, both tattoo artists and

patients reported chronic medical conditions as the most common

content. Allergy was the next most common, followed by other (which

included splenectomy and previous administration of streptokinase),

blood type, and end of life wishes. The information health care

professionals thought would be most useful to include were allergies

(87%) and chronic conditions (67%). Just over half (54%) thought end of life care requests would be useful. Surprisingly, a minority (37%)

thought a patient’s name would be helpful information and only 9%

felt a medical information identifying number would be helpful. In

the case of ID numbers, these apply only to the system in which they

are assigned and are not linked to the patient universally. Although

memberships to services like Medic Alert and various applications

connect an ID or a phone to a chart [20], going through the process to

access the information takes time. Clear, easily accessible information

can make medical alert tattoos valuable in emergent situations where

time constraints make it difficult to go searching for a patient’s

medical information.

Tattooing as a means of recording vaccination status was

proposed in 1959 but before recently was not popular [21], possibly

because of the high numbers of recommended vaccines in western

countries where tattoos are popular. Vaccination status was not seen

in medical alert tattoos in this survey; however, it closed before the

first COVID-19 vaccine became available. Currently internet searches

reveal that many people are getting virus and vaccine themed tattoos

both as a general topic and to indicate vaccination status. There

are examples of vaccination cards and even QR codes linked to the

European “Green Pass” which allows access to public sites/events if

the patient’s vaccination status is verified through this government

regulated system [22].

Text: All tattoo artists surveyed had only put simple text in

medical alert tattoos. However, 36% of patients reported using cursive

or fancy text in their tattoo. Using complex text can impair legibility,

particularly long term as ink bleeds within the skin and may blur

irregular edges of fancy text. Tattoo artists universally recommended

simple text to optimize long term legibility. Size is also a factor in long

term legibility. Artists were asked about the minimum size of text

they felt confident would be legible over a long period of time. Larger

was better with most people recommending approximately 1 inch

or 2.5cm, although several artists noted that this would depend on

technique. Namely, single needle technique (not used by all artists)

with careful ink deposition would allow smaller text to remain legible

for longer. So in addition to a clear font an experienced licensed tattoo

artist is important to guiding the minimum size of font to ensure long

term legibility if a small tattoo is desired.

Symbology: Symbols are widely used to quickly visually identify

information such as hazards, directions, and categories. 74% of

health care professionals surveyed felt that they would be more likely

to recognize a medical alert tattoo if a medical symbol was included.

Symbols can have varied meanings when used in tattoos [23].

Within the context of medical alert tattoos there is wide variation in

symbol use but the caduceus, rod of Asclepius, and star of life are

seen most frequently. These examples are associated with medicine

and para medicine. While these associations are an important aspect

of a symbol aiding in recognition, the symbol’s popularity is also

an important part of its usefulness in this context. One example of

the difference between accurate association and recognizability is

the blue circle. This symbol is accepted to be a symbol of diabetes

by many patients with diabetes as well as diabetes associations

[24], but is not widely recognized outside of these communities. Of

the health care professionals surveyed in this study, only 9% had

previously heard of a blue circle representing diabetes. Similarly

I>^v (‘I’m greater than my highs and lows’) is a popular symbol for

diabetes within these patient communities but would be unlikely to be recognized as medical information in an emergency. Symbols not

traditionally associated with medicine may be chosen by patients for

artistic or personal reasons, but may be less likely to be recognized

by emergency medical providers. Surveyed medical professionals

were split between which of three common medical symbols was

most recognizable. This may be influenced by type of medical care

practiced; pre hospital symbols tend to use the star of life, where the

caduceus and rod of Asclepius are seen more often in hospitals and

private clinics. Providers might more easily recognize the symbols

they see more often in their environment.

The interpretation of symbols alone can also be very problematic.

The medical symbols discussed can also be seen in tattoos on

people without intent of reference to their health. Caduceus, Rod of

Asclepius and Star of Life tattoos are commonly found on health care

professionals and even symbols specific for a particular condition can

be found on patients without the referenced condition. For example,

a parent may have a blue circle for a child with diabetes, or a person

may have a colored ribbon for a family member with cancer. One

case report above gives an example of a DNR tattoo containing only

a crossed out image of an old model of defibrillator pad, which may

not be recognizable as such to current providers [25]. While they can

aid in recognition, a symbol alone is not sufficient to reliably convey

medical information and assumptions should not be made about the

patient’s health status if they are found to have a symbol associated

with a medical condition.

Safety Issues: Tattoos and the process of tattooing are not

without risk. Transmission of viruses such as Hepatitis C and HIV by

tattooing is well established [23,26]. Although the risk of infectious

disease transmission is low with licensed professional tattoo shops,

particularly compared to those obtained in prison or by any nonprofessional

tattooists where needles may be shared [23], the risk of

any kind of infection is still an important factor to consider.

Under the US Food and Drug Administration tattoo inks fall

under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act [27]. The FDA has

never approved any ink for injection into the skin (although India

ink IS FDA approved for endoscopic submucosal injection) [28], and

many pigments used in tattoo inks are not even approved for external

skin contact [27]. While recommendations on sterility of tattoo inks

are provided by the Council of Europe [29], this regulatory body

does not have legal power to enforce these recommendations. One

study in Denmark found 10% of unopened stock bottles and 17% of

previously used stock bottles were contaminated with pathogenic and

non-pathogenic bacteria [30]. An FDA safety update in May 2019

also identified several available inks as contaminated with multiple

microorganisms [31].

Because of the artificial coloration in tattooing, benign or

malignant skin changes may be harder to identify [32], and the ink

itself may actually predispose to pathologic processes. Surveys of tattoo

ink contents have revealed Group 1 (carcinogenic to humans) and

Group 2B (possibly carcinogenic to humans) compounds which may

be present in the ink or produced with UV or laser exposure [29,33].

While multiple cases of skin cancers associated with tattoos have been

reported in the literature [33,34], a causative relationship is difficult

to establish and at this time occurrence of melanoma on tattoos is

considered coincidental [33]. However, inflammatory reactions have

been clearly linked to tattoo ink exposure and it is logical that cellular

changes associated with chemical exposure may directly or indirectly lead to malignant degeneration [35]. Additionally, tattoos may make

interpreting diagnostic studies for lymphatic spread of malignancy

more difficult; in some cases extra cutaneous pigment migration

may lead to false positive nodal spread of malignancy on PET [36] or

sentinel lymph node biopsies using dyes [37,38].

Exposure to tattoo ink can also trigger initial or recurrent

manifestations of underlying inflammatory conditions such as

sarcoidosis, various dermatosis, uveitis or severe allergic reactions that

may require surgical removal of the pigment [32,39-43]. While red

and black inks are most commonly associated with adverse reactions

it’s difficult to say whether the incidence is relatively higher than

other inks as relative frequency of use of different colors is unknown

but black and red appear most common anecdotally [41]. One of the

most common conditions depicted on medical alert tattoos, diabetes,

may lead to complications of healing a tattoo if blood glucose is not

well controlled [39].

Temporary medical alert tattoos are commercially available and

often targeted to children [44]. These commercial tattoos are usually

FDA approved with low incidence of adverse reactions, whereas

homemade temporary tattoos such as those made from henna may

be associated with severe allergic and other reactions [45]. Safety data

for use of tattoo ink in children is not available. Tattoos may become

distorted and illegible with growth, making them impractical for

children and adolescents. There are also legal age cutoffs for tattooing

in many countries and states [46], related both to lack of safety data

and the ethical issues with inflicting pain without clear benefit on

those under the age of consent.

Social Issues: Despite the increasing prevalence of tattoos in

western society, there is still a recognized stigma associated with them

in many groups. Historical and contemporary literature has frequently

shown a link between tattoos and antisocial behaviors [47-51].

While there does seem to be a link with early age body modification

and risk taking behavior, older adult studies may have significant

selection bias as they frequently draw their data from criminal or

mental health facilities [23,47,52]. In fact, a recent European survey

showed that people with body modifications including tattoos and

piercings reported higher self-esteem and fewer symptoms of social

impairment and sleep disorders than their non-modified control

group [53]. A study from the same year reported that 16% of tattooed

people surveyed regretted at least 1 tattoo, but the rates of regret were

significantly higher in those who were first tattooed before age 21 [54].

Another study from 2012 looked at motivations for wanting tattoos

removed and most common reasons were professional (for example

rules at work about visible tattoos or applying for a different type of

job) or personal (most commonly a change in relationship status with

a partner named or depicted in a tattoo) [55]. Regrets about tattoos

are very rare in military personnel [23]. In the case of a medical alert

tattoos, comments by our respondents did not express regret. In fact,

in both this study and a prior smaller study on diabetics with medical

alert tattoos patients felt encouraged or supported by family and or

medical providers with only one example of a negative experience in

the smaller study [56].

Motivations: A study by Kluger et al asked 5 diabetic patients

about their motivation for getting medical alert tattoos [56]. One

reported metal allergy and the rest inconvenience of jewelry. The

current study also found that inconvenience and cost of jewelry was

also a large contributor to the decision to get a medical alert tattoo, but also found that personal art and a feeling of mastery over the chronic

condition were important motivators for many people. Considering

that these non-medical reasons are sometimes motivators for getting

medical alert tattoos it is understandable why some patients may not

be receptive to recommendations from health care professionals on

their use. However, the majority of patients seem to be motivated

by practical reasons and based on this study would be receptive to

guidance.

Accuracy: In the case studies above there are several examples

of errors including simple and identifiable spelling errors as well as

inaccuracy of the content to the patients’ current clinical situation.

Arguably the biggest problem with the information contained in

medical alert tattoos is that it is self-reported. As any clinical provider

will attest, patient self-reports of their medical history are not

infallible. In one study 7% of service members self-reported incorrect

blood types or Rh factors on a screening form for a walking blood

bank [57]. In the blood type tattooing program during the cold war,

the incidence of incorrect tattoos was estimated to be as high as 10%

[18]. The consequences of transfusion with incorrectly cross-matched

blood may be fatal. The more recent issue of restrictions on people

refusing COVID-19 vaccination could conceivably serve as motivation

for incorrectly reporting vaccination status through a tattoo. In cases

where it is possible to confirm information in medical alert tattoos

this should be done, but when that is not possible weighing risks and

benefits of acting on this information can be helpful. For example,

acting on an incorrect DNR tattoo can have fatal consequences,

whereas acting on an allergy tattoo has minimal risk.

DNR tattoos: Under US federal law “an advance directive is

defined as: A written instruction such as a living will or durable power

of attorney for health care, recognized under state law […] relating

to the provision of health care when the individual is incapacitated.”

[58]. Depending on state regulations a tattoo may or may not qualify

under this definition. In the UK, the requirement for a valid advance

directive is that it is in writing, specifies the patients exact wishes and

is signed by the patient and a witness [59]. In Finland, according to

the National Authority for Medico legal Affairs, a tattooed consent is

not legally equivalent to a signed document [60].

A recent article in the Oregon Law Review examined this topic

in the context of US law [61]. Two states, Florida and Oregon,

require advance directive or Physician Orders for Life Sustaining

Treatment (POLST) documents to be printed on specific color paper

which more explicitly invalidates tattoos. Some states do recognize

advance directive proxies in the form of cards or jewelry, and the

author suggests that tattoos could theoretically be used as proxies

if approved by a given state. This would be particularly useful in

states like Oregon where copies of patients’ POLSTs are available

online and indication of their existence for a given identified patient

could be enough to quickly confirm the patients’ wishes and guide

management accordingly.

In the absence of clear and specific verbiage in many state laws

on this subject, interpretation can be aided by hospital specific ethics

consultation. To quote the committee in Holt et al’s case study [62],

“what might be seen as a caution could also be seen as standing on

ceremony, and […] the law is sometimes not nimble enough to

support patient-centered care and respect for patients’ best interests”.

To best interpret the information presented in DNR tattoos, providers

must be aware of their local laws and apply them to each individual clinical circumstance with the patients’ best interests at the core of

their intent.

Opinion articles have suggested that DNR tattoos should never

be considered equivalent of an advance directive [63]. This article also

brings up the same issue with an example of a piece of jewelry that

simply stated “DNR”. In this case the patient presented with need for

a laparotomy which was done, and when recovered the patient told

providers the DNR referred only to not wanting a prolonged ICU stay.

Of the case reports reviewed on DNR tattoos, only 3 of 5 represented

confirmed accurate information about the patient’s end of life wishes.

One did in fact inform provider decision making in the absence of

next of kin, and after the patient was made officially DNR but before

they expired their paper DNR document was found confirming the

information in the tattoo [62]. One of the two that did not represent

accurate information was in an elderly male who had previously been

DNR but whose health had improved and he changed his legal status

[64]. The argument was that tattoos can’t be valid because they are not

changeable, which is inaccurate; Tattoos can be changed in multiple

ways. Complete removal or elaborate cover up of a tattoo particularly

one in black ink is time consuming and expensive. However, adding

a line crossing words out can be done quickly and often without an

appointment. As such simple changes to a tattoo can in some cases be

easier than changing a legal document. In this case report it is unclear

if any guidance on changing the tattoo was given. In situations like

this it is valuable for providers to be aware of options for removing or

changing tattoos as patients’ medical information changes.

Another example of an inaccurate tattoo is a patient who had the

letters “DNR” tattooed on his chest because he lost a bet during a

poker game [65]. There are also a few other general media articles

on people who have DNR tattoos that are meant for style rather than

actually conveying medical information. This further supports that

providers need to be wary of the accuracy of these tattoos. In general

when people get these tattoos for reasons other than conveying end

of life wishes they tend to be relatively simple, small, and very rarely

say anything other than the letters DNR. However, there are examples

of small simple DNR tattoos being accurate expressions of patient

wishes and there are probably examples of complicated tattoos being

inaccurate. With any expression of patient wishes there is a duty to

confirm them if possible and if only limited information is available,

if a provider acts in good faith with the information available there

is ethical and legal precedent for taking DNR tattoos into account

which can be further guided by consultation with the hospital ethics

committee.

Validity can be considered similarly with any nonstandard

advance directives- a declaration of wishes is only useful when it

can be confidently applied to the clinical situation the patient is in.

Arguably one can compare the contents of tattoos to the patient in

a moment of lucidity saying exactly what is written in the tattoo.

For example, if a patient woke and said “DNR”, it would not be

appropriate to assume that means they want no interventions. The

UK Mental Capacity Act states that a provider should not incur

liability for providing treatment in the patient’s best interests if they

do not know or are not satisfied that a valid and applicable advance

decision exists [59]. One must be satisfied that the statement is

clear enough to be valid and applicable to the situation, which very

often requires further thoughtful investigation even in the case of

a patient presenting with an advance directive document. If able to effectively communicate, these patients will often agree to advanced

interventions if their counseled that their condition is likely reversible

and they have a reasonable chance of recovery. The non-standard

formats of living wills and other documents and the difficulties in

interpreting and applying what is written has contributed to moving

towards more standard advanced directives and proxies as discussed

above. Regardless of the format, communication of wishes is only

as useful as the content and the applicability of that content to the

clinical situation.

Similarly to standardizing paper and electronic advance

directives, standardizing medical alert tattoos may also be useful. This

could aid in recognition, improve clarity of messages conveyed and

as discussed above potentially allow for legal recognition as a proxy

to a full advance directive [61]. One article suggested creating flash

that can be copyrighted by the American Academy of Hospice and

palliative medicine reading as follows: “Consider do not resuscitate:

I concur to the guided and educated decision of my medical team for

medical futility in my present clinical scenario.” [66]. While it seems

this did not come to fruition, the idea of providers partnering with

national associations with the guidance of ethical and legal teams is a

useful one. Further collaboration on this issue is needed.

Limitations of this study

The population of patients with medical alert tattoos is a difficult

one to study. Determining prevalence is difficult as these tattoos are

usually done without involvement of the medical system. Incidence

is even more difficult to determine as the population controlling the

incidence (tattoo artists) exist outside the culture of medical research.

Outreach through social media as done in this study and prior

smaller studies is problematic in that there is notable response bias

[56]; patients with medical alert tattoos likely have more interest in

completing a survey on something that relates directly to them, and patients with chronic medical conditions without medical alert tattoos

may be more likely to respond if they are already considering getting

one. The technology of tattooing itself is also quite old. While it’s still

being done many questions were encountered in the process of this

study about newer technologies to store medical information such as

microchips. However, similar problems come up where information

may be out of date, inaccurate, not recognized or not compatible

with locally available technology. Most importantly, the data on this

subject overall is not strong enough to definitively say medical alert

tattoos can improve outcomes for patients with chronic medical

conditions. That kind of certainty with all the possible confounders

would likely require a randomized control trial which is not a

practical option. We have tried to collect data from patients, artists

and medical professionals to guide recommendations. Although we

were not able to obtain large sample sizes, to the author’s knowledge

this remains the largest study on this topic to date.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The results of our survey support that many medical professionals

believe that medical alert tattoos can be an appropriate media for

conveying medical information. It is important to note that the

appropriateness varies on a case-by-case basis driven by the patient’s

medical history and motivations as well as the clinical setting. Based

on the current lack of structured guidance on this subject coupled

with the already wide use of medical alert tattoos, whether or not

medical alert tattoos are a good idea or not is somewhat of a moot

point as it is clear patients are going to get them regardless of the

presence or absence of guidance. However, as most patients report

that they would be receptive and that there seems to be room for

optimizing their usefulness, formal recommendations are warranted.

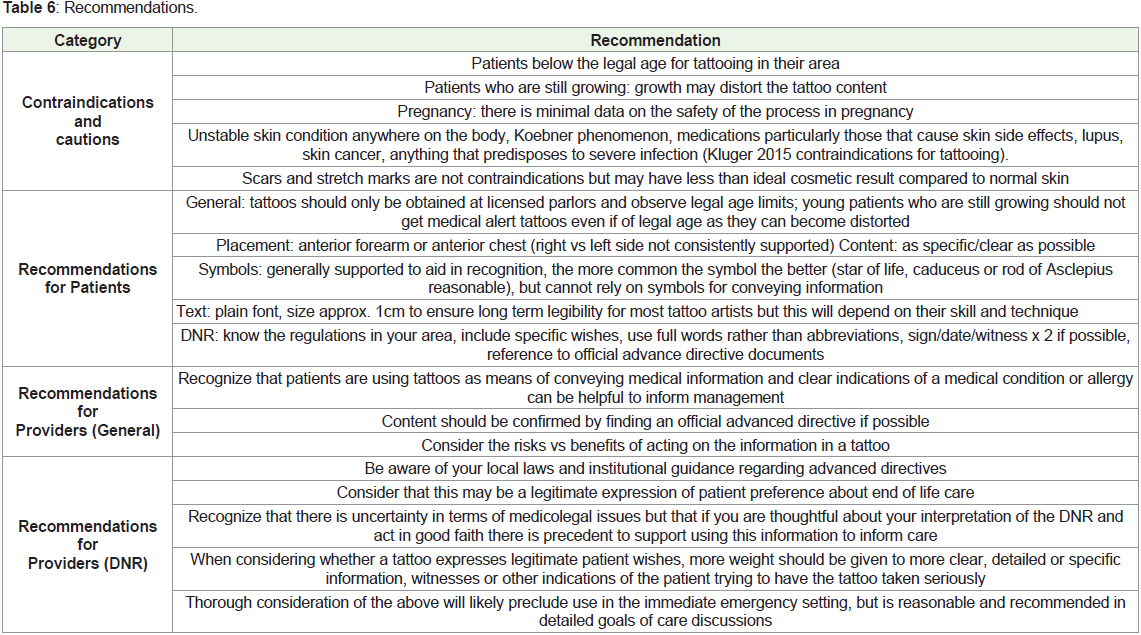

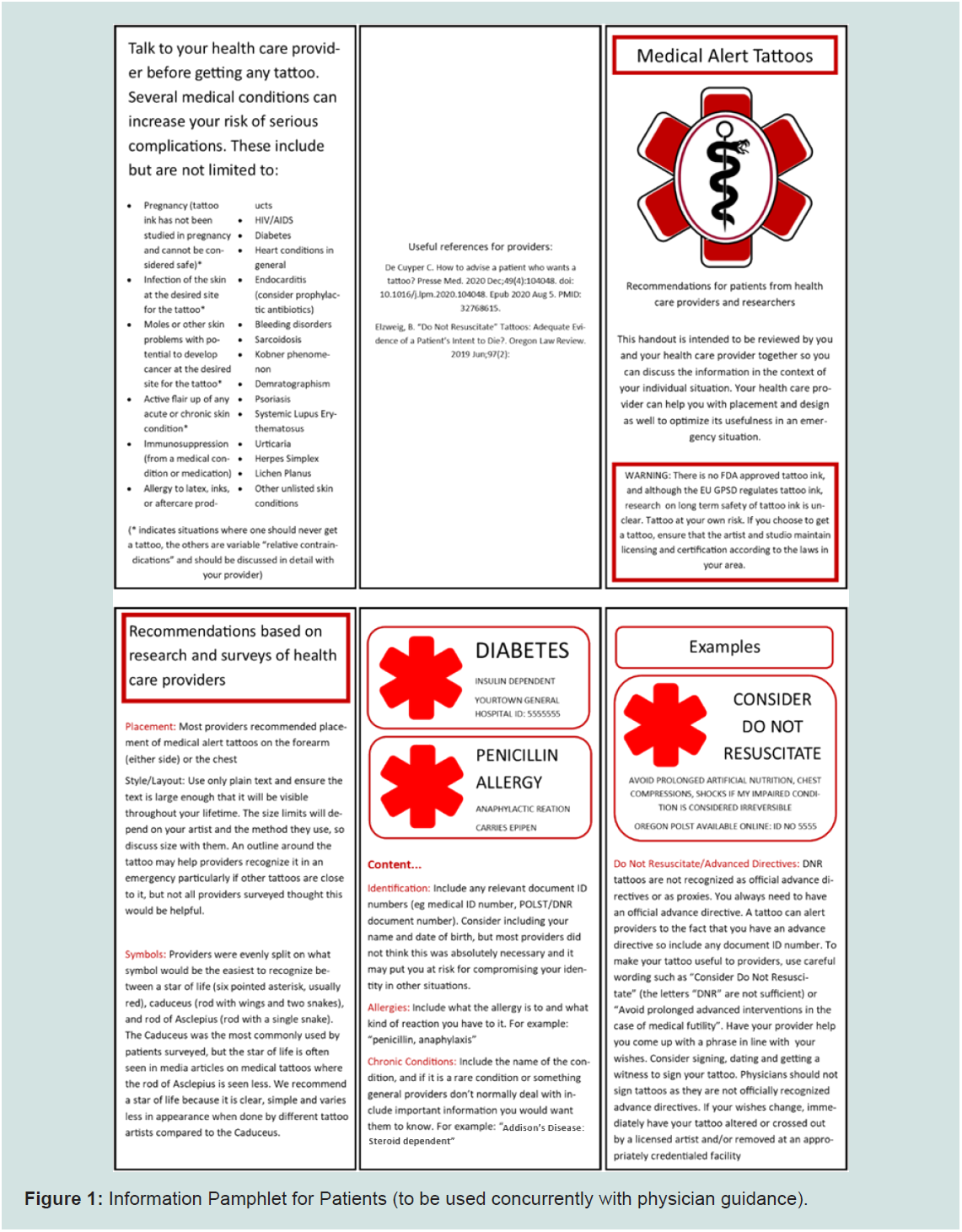

As such the following recommendations are proposed for patients

and health care providers (Table 6 and Figure 1).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr Gemma Kelleher for her

support of this project through the design and ethical approval

process, and Dr Laszlo Kiraly during the editing and submission

process.