Journal of Hematology & Thrombosis

Download PDF

Case Report

An Atypical Case of Hepatosplenic T Cell Lymphoma

Gosnell HL1* and Stump MS123

1School of Medicine, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, USA

2Section of Pathology, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, USA

3Dominion Pathology Associates, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Gosnell HL, School of Medicine, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, 1 Riverside Circle, Suite 105, Roanoke, Virginia 24016, Virginia, USA, Phone: 252-241-4428; E-mail: haileylg@vt.edu

Submission: 07 July, 2020;

Accepted: 19 August, 2020;

Published: 21 August, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Gosnell HL, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma (HSTL) is a rare, aggressive subtype

of extra-nodal lymphoma characterized by hepatosplenic presentation

without lymphadenopathy that is typically seen in adolescents and young

adults with a male predominance with bone marrow involvement. We

present a case of a 55 year old woman with past history of pulmonary

embolism, deep venous thrombosis and type II diabetes who complained

of diffuse abdominal pain (worst in the LUQ) and lightheadedness.

Ultimately, the patient was diagnosed with splenic hematoma and

hemoperitoneum. This diagnosis necessitated splenectomy which

revealed a markedly enlarged and ruptured spleen. Microscopic analysis

with immunohistochemical stains showed a prominent abnormal T-cell

population involving the splenic red pulp consistent with HSTL in this

patient. Follow-up bone marrow biopsy was negative for involvement.

We present this patient’s case due to her unique demographic and the

atypical clinical features of her disease including lack of bone marrow

presentation.

Introduction

Hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma is a rare, aggressive subtype

of T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma with extra-nodal and systemic

presentations [1]. This neoplasm usually derives from cytotoxic T

cells expressing a gamma-delta receptor type [2]. Though the etiology

of the disease is unknown, as much as 20% of HSTL cases arise in

the setting of chronic immune suppression [3]. Clinical findings

include hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, systemic symptoms, anemia,

thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and liver enzyme abnormalities in

the absence of lymphadenopathy [4]. The disease predominately

affects young males (20-35 years of age) and has a rapidly progressive

course with mean overall survival of less than 16 mos. regardless of

treatment [5].

We present an atypical case of HSTL both in demographic and

clinical course. Our patient, a 55 year old female with past history of

pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, and diffuse abdominal

pain, presented from an outside hospital with a immediate history

of traumatic splenic rupture and hemoperitoneum, necessitating

splenectomy. Architectural distortion noted on microscopic analysis

of splenic tissue as well as follow up immunohistochemistry revealed

an underlying diagnosis of HSTL. While reports of unusual HSTL

cases exist in the literature, this case is one that is granzyme negative

and lacks bone marrow involvement. Analyzing pathophysiology in

light of unusual case presentations can improve understanding of a

disease and the most appropriate treatment option.

Case Description

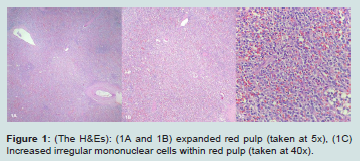

A 55 year old female with a past history of pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, and type II diabetes presented to the emergency department upon referral from an outside facility with lightheadedness and diffuse, worsening abdominal pain accompanied by nausea and vomiting with concern for traumatic splenic rupture. At the referring institution, the patient was noted to have a splenic hematoma and hemoperitoneum on CT as well as a hemoglobin value of 7.5 g/dL and marked hypotension (systolic blood pressure measured in the 80s). The patient was given K centra and three liters of fluid on transport to our facility (Figure 1).

On physical exam, the patient was noted to be hypotensive with sinus tachycardia (100s), pale conjunctivae, diffuse abdominal tenderness (most severe in the LUQ), and dry, pale skin. No external signs of injury were noted. FAST exam confirmed a large amount of abdominal free fluid. The patient was noted to have acute

blood loss anemia likely from either splenic hematoma or splenic artery aneurysm. One liter of blood was promptly transfused and a splenectomy was performed.

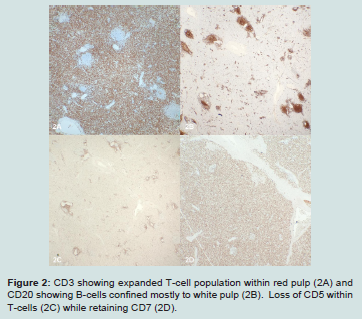

Intraoperatively the spleen was noted to be essentially in pieces with clotted blood. Microscopically the white pulp appeared intact but infringed upon by an expanded red pulp containing a lymphoid process sinuses and cords. These cells consisted of medium-sized, atypical lymphocytes, exhibiting irregular nuclear borders and clear cytoplasm. Background histiocytes exhibiting hemophagocytosis as well as scattered background lymphocytes and immunoblasts were noted. Review of the gross description, provided by a rotating pathologist assistant student, revealed the spleen weighed 862 grams (Figure 2).

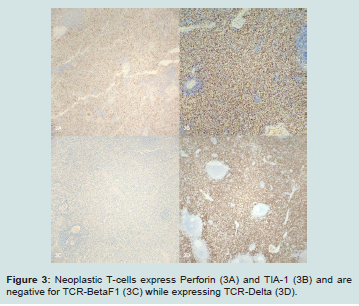

Suspecting an underlying hematologic malignancy, immunohistochemical stains were performed and the initial battery identified an expanded T-cell population within the red pulp that expressed CD3 and CD7 but was negative for CD5. Full workup revealed this population expressed CD3, subset CD8, CD7, TIA-1, perforin, minimal CD56 and TCR delta while being negative for CD4, CD5, TCRBF1, granzyme B, CD30, CD57, CD34, CD99, TdT, EBER ISH and B-cell markers. PCR studies identified TCRG and TCRB rearrangements consistent with a clonal T-cell population. Unfortunately, flow cytometry was not performed. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy and review of the peripheral smear from an admission specimen did not show an abnormal leukocyte population. Given these findings a diagnosis of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma was made and this case was sent for second opinion to University of Virginia Health System with agreement of that diagnosis.

Figure 1: (The H&Es): (1A and 1B) expanded red pulp (taken at 5x), (1C) Increased irregular mononuclear cells within red pulp (taken at 40x).

Figure 2: CD3 showing expanded T-cell population within red pulp (2A) and CD20 showing B-cells confined mostly to white pulp (2B). Loss of CD5 within T-cells (2C) while retaining CD7 (2D).

Figure 3: Neoplastic T-cells express Perforin (3A) and TIA-1 (3B) and are negative for TCR-BetaF1 (3C) while expressing TCR-Delta (3D).

A follow-up bone marrow biopsy, performed at an outside hospital, showed hypercellular marrow with mild CD3+ T cell lymphocytosis without abnormal immunophenotype. Flow cytometry of the bone marrow also did not identify a T-cell lymphoproliferative process. The patient’s bone marrow karyotype was found to be normal. FISH specifically looking for isochromosome 7q was negative. Cancer gene mutation panel did not reveal any CML or myeloproliferative neoplasm related DNA mutations or RNA translocations (Figure 3).

Discussion

We presented a unique case of HSTL lacking bone marrow involvement in a 55 year old female. The patient’s hematologic malignancy was not readily apparent until histological analysis was performed post splenectomy (indicated for perceived splenic hematoma and hemoperitoneum). While flow cytometry was not performed, the morphology and judicious use of immunohistochemical stains provided key information in support of a HSTL diagnosis.

The patient’s demographic and clinical course made solidifying a case for an HSTL diagnosis challenging. As aforesaid, hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma namely affects young males and our patient is a middle-aged female. In addition, the disease almost always shows some degree of bone marrow involvement [6,7]. Our patient’s clinical picture did not reflect bone marrow involvement. Our patient’s atypical T cells were negative for granzymes B and M, and positive for perforin. The atypical T cells of HSTL patients usually express granzyme B and fail to express perforin [5,8]. Amid the aspects of this patient’s case that failed to conform with a textbook case of HSTL, there were a number of factors, taken together, made this diagnosis

the most likely.

Despite an atypical demographic and case presentation, the diagnosis of HSTL was chosen for this patient in light of splenic histology, T cell markers, and PCR studies. On microscopic analysis, our patient’s splenic white pulp appeared intact but infringed upon by red pulp sinuses and cords consisting of medium, atypical lymphocytes exhibiting irregular nuclear borders and clear cytoplasm. The splenic histology noted in this description is consistent with that described in a typical HSTL case (i.e. neoplastic cells surrounded by rims pale cytoplasm infiltrating the cords and sinuses of splenic red pulp with atrophy of white pulp) [9]. Like those of a typical HSTL case, the patient’s T cells displayed a gamma-delta immunophenotype, with rearranged TCRG and TCRB genes noted on PCR.

Within the differential diagnosis, an atypical large granular T cell Leukemia/Lymphoma (T-LGL) was considered in light of the patient’s demographic, clinical course, and lab results. Our patient’s demographic is more in line with that of a typical case of T-LGL (equal male to female ratio affected with majority of cases

presenting between 45-75 years of age) [10]. The lack of bone marrow involvement noted in our patient’s case is also made more plausible by a T-LGL diagnosis, as bone marrow involvement is variable in T-LGL [11].

A number of core features of this patient’s case including splenic histology, lack of abnormal lymphocyte population on peripheral smear, and the immunophenotype, did not match up with a T-LGL diagnosis, however. Microscopic splenic findings in a typical case of T-LGL show infiltration and expansion of the red pulp cords and sinusoids by T-LGLs with sparing of the often hyperplastic white pulp7 a description not consistent with the splenic architecture noted in our patient’s case. Additionally, the atypical T-cells in T-LGL usually display a CD57+, granzyme B+, alpha/beta+ immunophenotype, with only rare cases expressing gamma/delta [12]. Finally, there was no peripheral blood involvement or even a lymphocytosis at the time of splenectomy or bone marrow biopsy that would be expected in T-LGLL.

Conclusion

Our case illustrates and unusual presentation of HSTL with spontaneous splenic rupture in a patient that does not fit the characteristic demographic. The lack of bone marrow involvement is also unusual compared to cases reported in the literature. This case also highlights the need for a pathologist to have a high degree of suspicion and a low threshold for performing stains to exclude neoplastic processes in cases of splenomegaly that may not have abundant history or is otherwise unexplained. Furthermore, an

extensive immunohistochemical workup and wisely reviewing all available material present can usually yield an accurate diagnosis despite not having all possible testing modalities available.