Journal of Nutrition & Health

Download PDF

Research Article

Socioeconomic Determinants Influencing Nutritional Status of Children in Sekhukhune District of Limpopo Province in South Africa

Phooko-Rabodiba DA1, Tambe BA2, Nesamvuni CN3 and Mbhenyane XG4*

1Department of Human Nutrition, University of Limpopo, South

Africa

2Division Human Nutrition, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

3Department of Nutrition, University of Venda, South Africa

4Division Human Nutrition, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

*Address for Correspondence: Mbhenyane XG, Professor and Research Chair, Division Human Nutrition, Stellenbosch University, PO Box 241, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa; Tel: +2721 938 9135, E-mail: xgm@sun.ac.za

Submission: 16 February, 2019;

Accepted: 13 August, 2019;

Published: 16 August, 2019

Copyright: © 2019 Phooko-Rabodiba DA, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

South Africa has adequate food supplies to feed the entire

population at national level. However, reports have shown evidence

of under-nutrition among certain parts of the population due to lack

of access. The aim of the study was to determine the relationship

between socioeconomic status of the household and the nutritional

status of children one to twelve years (1-12 years) in Sekhukhune district

of Limpopo Province.

The study used exploratory designs. A structured interviewer-led

questionnaire was used to determine socio-economic parameters and

standard anthropometric procedures. All analyses were done using

Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 20. A total number of

180 mother-child pairs participated in the study. The sample distribution

for children was 46.1% male and 53.9% females. Most mothers were

unemployed and spent less than 500.00 ZAR (≈50 USD) per month to

purchase food for the household. There was a high (39.6%) prevalence

of stunting among children under the age of 60 months, a medium

prevalence of underweight, and a low prevalence of wasting in all

children. Most caregivers were overweight or obese. Maternal level

of education and household income was significantly associated with

anthropometric status indicators (p<0.05).

This study revealed a high rate of unemployment, poor household

income and purchasing power, and high level of food insecurity.

This might have contributed to the high prevalence of stunting and

a medium prevalence of underweight recorded in the study. There is

urgent need to address basic needs to improve access to nutrient rich

foods and health care.

Keywords

Socioeconomic determinants; Nutritional status; Children under 12 years; Limpopo province; South Africa

Introduction

Malnutrition remains a problem in many parts of the world,

815 million people throughout the world are malnourished due to

insufficient food in 2016, up from 777 million in 2015 [1]. Chronic

undernutrition could result in stunting, wasting, and underweight.

According to recent studies, approximately 52 million children under

five suffer from wasting; their weight is too low for their height, while

155 million suffer from stunting globally [2]. In Africa, an estimated

47 million children are stunted, 35 million are underweight, and 11

million are wasted according to Kleynhans et al. [3]. These children

begin their lives at a marked disadvantage: they face learning

difficulties in school, earn less as adults, and face obstacles to

contribute in their societies [2].

The South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2016 for

children aged between one to five years showed a high rate (27%

and 22%) of stunting at national level and in Limpopo Province

respectively [4]. Another study in South Africa by Shisana et al. reported 26.5%, 11.9%, and 9.4% stunting in one to three year old’s,

four to six year old’s [5], and seven to nine year old’s respectively at

national level. Sekhukhune district exhibited a high rate of stunting

(36%) in children 13 to 215 months of age according to Food

Insecurity and Vulnerability Information Management System for

South Africa [6]. Greater Sekhukhune District Municipality (GSDM)

is an underprivileged area and was identified as a nodal site by

Integrated Sustainable Rural Development Programme (ISRDP), due

to its high unemployment rate of 69% to 82.4% [7].

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund

(UNICEF) conceptual framework of child malnutrition explained

the determinants of undernutrition. This framework classifies factors

into three levels: the immediate, the underlying, and basic causes.

Dietary intake and infections are classified as immediate causes [8-10]. Household food security, inadequate care and feeding practices,

unhealthy household environment, and limited access to healthcare

services are the underlying causes [11,12]. While basic causes

include limited land for cultivation, parental low level of education,

employment status, and household income, just to name a few [13,14].

This study was conducted in Limpopo province because of the

high (49.9%) unemployment rate compared to other provinces

and because of the inadequate information available on the child

nutrition status at the Sekhukhune district level [15]. The high rate

of unemployment and poverty in the province could have an impact

on nutritional status of the children between 1 to 12 years. This

study, therefore, aimed to investigate determinants associated with

underweight, stunting, and wasting in the Sekhukhune District in

Limpopo Province of South Africa.

Materials and Methods

The study used an exploratory and correlational research design

and it aimed at establishing a relationship between socioeconomic

characteristics of the mother and nutritional status of children aged 1 to 12 years. The study used both quantitative and qualitative data

collection techniques to collect data over a period of 24 months.

The study setting was GSDM, one of the five districts of the

Limpopo Province contributing to 20% of the provincial population

of 5.5 million. One local municipality in GSDM, Makhuduthamaga,

was purposively selected.

The study populations were mothers/caregivers with children 1 to

12 years of age living in Makhuduthamaga Local Municipality of GSD

Min Limpopo Province. Makhuduthamaga Local Municipality M

constitutes 27% (262921) of the total population of GSDM with 13.8%

(134068) children aged 0 to 17 years, and approximately 100 villages

[15]. The calculated sample size was 180 households, giving a total

360 mothers/caregivers and their children calculated using a Slovin

formula to give 80% power. Simple random sampling was used to

select nine villages, which is approximately 10% of the total number of

villages in Makhuduthamaga. All villages from the municipality were

identified using a local map, numbers were assigned, and nine villages

were blindly selected. Systematic random sampling was used to select

households from the selected villages. Upon entering each village, the

first house from the point of entry or the chief’s kraal was selected and

thereafter every fifth house on alternate sides were selected. Twenty

households per village were selected until the study population of 180

was reached. From each household, one child between 1 to 12 years

was randomly selected to be part of the study group. If the household

had more than one child within the selected study age group, every

child was allocated a number and the child with the lowest allocated

number was selected. If the household had no children in that age

group, the household was skipped. The total sample was thus 180

mothers/caregivers and 180 children aged between 1 and 12 years.

Data collection:

A questionnaire was used to collect data from participants

regarding socioeconomic status and anthropometric characteristics

in their various households. The socioeconomic characteristics

collected included: age of the child; age, educational level, marital

status, employment status and income of the mother; total household

income and household income spent on food while anthropometric

parameters of both adult/caregiver and child included weight, height,

and mid upper arm circumference. The questionnaires included close

and open-ended questions, and the questionnaires were administered

by the researcher and the assistant using the local language. The length

of children less than three years who were unable to stand erect,

were measured using a height board with the caregiver supporting

the torso and legs pressed downwards and the other family member

supporting the head as the researcher took measurements. The

children were measured twice, and the average was computed. The

heights of children who were older than three years were measured

using an electronic height rod. The subject was standing erect,

looking straight ahead without tipping the head down. The top of

the ear and the outer corner of the eye were in a line parallel to the

floor (Frankfort plane).Weight was measured twice in light clothing

and barefooted using a Tanita electronic scale and the average weight

was recorded. However, in cases where the child could not stand on

the scale, the mother’s weight was taken with and without the baby,

the latter was subtracted from the former weight and the difference

was recorded as the child’s weight. The scale was calibrated daily and zeroed before collecting data on each participant [16]. The mid upper

arm circumference was measured with a measuring tape [17].Ethical considerations:

The Higher Degrees Committee of University of Venda approved

the research proposal. An approval letter and oral permission was

received from the Municipal Manager of Makhuduthamaga Local

Municipality, and traditional authorities respectively. The study

was explained to the participants, who were then requested to fill a

consent form to be part of the research. The procedures complied

with requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki (2008).Data analysis:

Data was entered to a Microsoft Office Excel sheet and exported

to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 for

data processing and analyses. Anthropometric data of children was

analysed using Z-scores and comparing it to the National Centre for

Health and Statistics (NCHS) for children above five years, and the

WHO standards was used for children under five years of age [18]. The

anthropometric indices were interpreted as stunting, (height-for-age

<-2SD) and severe stunting (height-for-age <- 3SD), wasting (weightfor-

height <-2SD), severe underweight (weight-for-height <-3SD),

and overweight (weight-for-age >2SD) using WHO classification of

malnutrition in children. Descriptive statistics were used for analysing

the socio-economic variables. The relationship between different

socio-economic variables, particularly mothers’ employment status

and nutritional status, was statistically analysed using Pearson’s Chisquare

Test. Variables were considered significant if P-values were

less than 0.05. Income is reported in South African currency rand or

ZAR.Results

Sociodemographic characteristics:

A total number of 180 mother-child pairs participated in the

study. The sample distribution for the children were 46.1% male and

53.9% female. The minimum age of the children was 12 months, the

maximum age 142 months, while the average age was 38 months.

Regarding the caregivers’ information, 73.9% of children were taken

care of by their mothers, 23.3% by their grandmothers, and 2.8% by

other siblings or relatives. In addition, 87.2% of the caregivers were

between 20 to 59 years of age, 1.7% between 13 to 19 years, and 11.1%

greater than 60 years. Majority (53.3%) of the caregivers had high

school level of education, 20.6 % of caregivers had primary school

level, 23.9% never attended formal school, and only 2.2% obtained

tertiary level education. A caregiver was regarded as single if he/she

was unmarried or widowed, and married if he/she was married or

living together with a partner. Most caregivers (53.4%) were single,

whilst 46.7% were married.Regarding the economic status of the households, most of the

caregivers (92.2%) were unemployed while only 7.8% were employed.

In addition, only 21.1% of fathers were employed, 24.4% unemployed,

and 54.5% of households were without fathers living with them.

More than half (53.9%) of the children were financially supported

by grandparents, 12.2% by their fathers, 9.4% by their mothers, and

7.8% by other members of family, whereas 16.7% had no financial

supporter.

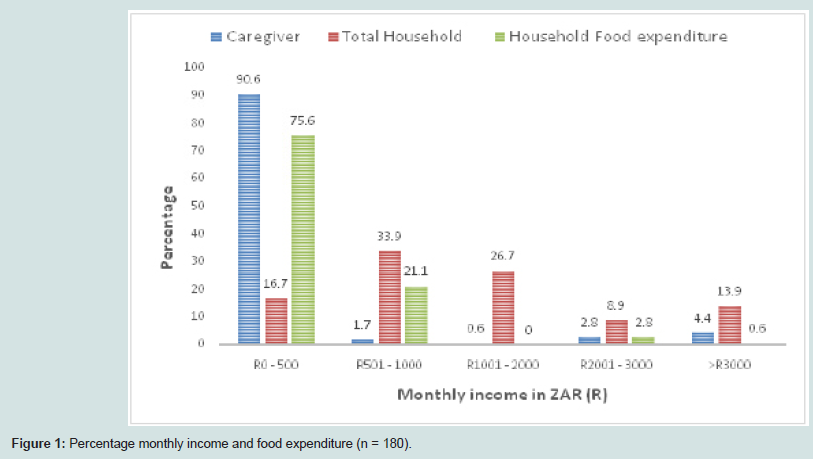

Figure 1 shows that most caregivers earned less than 500

ZAR monthly and therefore lived below the poverty line, which is

estimated at 1 USD/day or R10.00/day [19]. Household additional

income was also assessed. Out of the 81.1% of households who had

an additional income, 76.7% received income from child support

grant, 1.1% received old age pensions, and 3.3% received resources

from family members. The total household income was the sum of the

income from the caregiver and additional income from other sources.

Figure 1 shows that half (50.6%) of the households had a total income

of less than 1000.00 ZAR per month per household, 35.6% had a total

income of between 1001.00 ZAR and 3000.00 ZAR. This shows very

poor households falling into the low-income group. Regarding food

purchasing power per household, the majority of caregivers (96.7%)

spent 1000.00 ZAR or less on food on a monthly basis Figure 1.

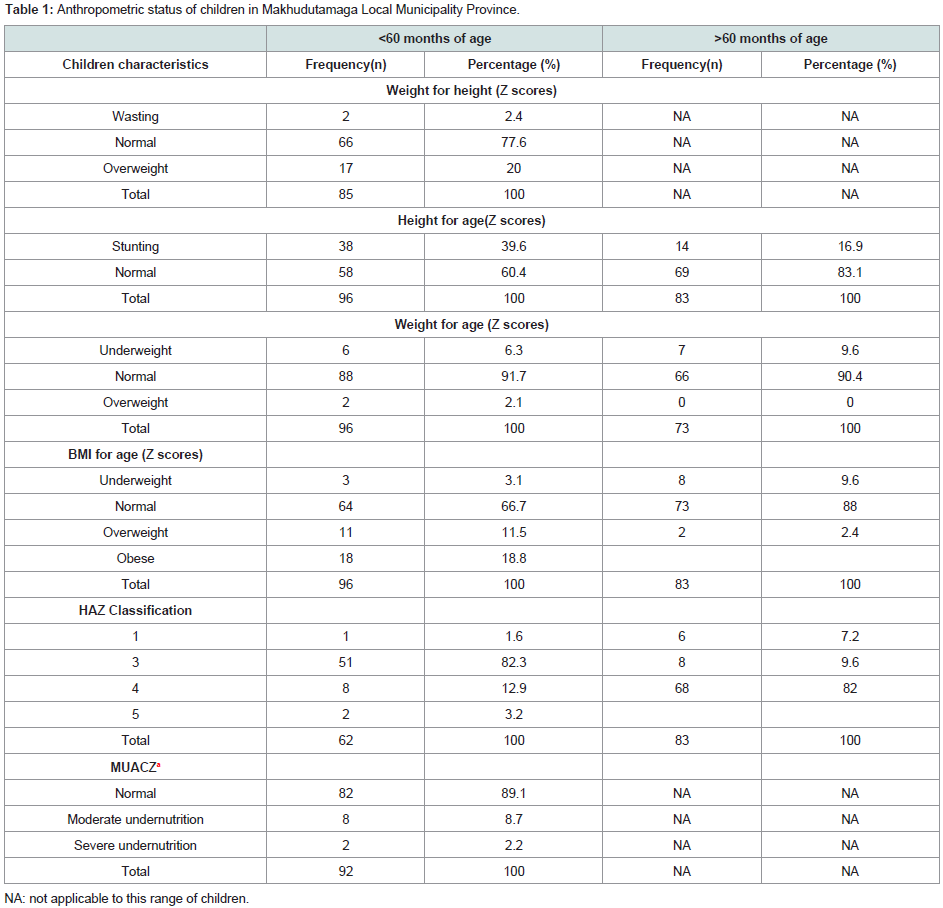

Anthropometric status of children and caregivers:

Table 1 shows the anthropometric indices of children. These have

been separated according to age starting with below 60 months and

the other above 60 months. There was a high rate of stunting at 39.6%

for children below 60 months, which is a significant health concern

since it is above 20% [20,21]. There was a low rate of wasting and

undernutrition, while the children who were overweight and obese

were 20% and 18.8% respectively.The data shows that 16.9% of the children above 60 months were

stunted and low rate of underweight. Low overweight and obese rates

are observed in this group compared to the below 60 months old

children Table 1.

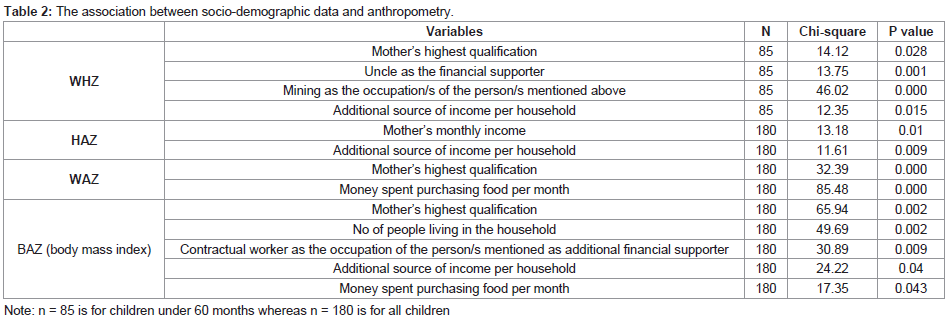

Table 2 illustrates associations between variables using the Chi

square test. Only variables which have shown significance at p<0.05

have been included. The data shows that the anthropometric indices

are associated with socio-demographic parameters that are typical for

a poor household, such as mother’s income and number of people in

the household Table 2.

Discussion

The results from the current study showed that most children

were cared for by their mothers (73.9%) or grandmothers (22.2%).

A similar care pattern was observed in the 1999 NFCS-SA wherein

63% of children were taken care of by their mothers and 21% by

grandparents. The findings are contrary to the research results by

Madhavan and Townsend which showed that high unemployment

rate push men and women to migrate to urban areas [22], leaving

children in the care of aunts and grandparents. The majority (87%)

of mothers/caretakers were between 20 to 59 years of age. This

reflected the available time and physical strength for taking care of

children. It also showed that the information given was reliable as it

was given by mature adults. Others reported that increased maternal

age may reflect the maturity and the availability of resources in terms

of money and time for rearing children [23].There were few childheaded

households.

The current findings revealed that approximately half of the

mothers/caregivers had attended high school, whilst 20.6% had

attended primary school, and 23.9% were illiterate. In addition,

maternal level of education was significantly associated with wasting

(p=0.028) and risk of underweight (p=0.000). This is because

education increases awareness and understanding of health issues,

proper hygiene practices, and financial security [23]. The results

are similar to the findings from the SADHS 2016 whereby 34% of

mothers had attended high school and 6% primary school [24].

The 2011 South African census showed that 20.9% adults above 20

years were illiterate, 21% had grade 12, while only 6.1% had tertiary

qualifications [25]. The study findings also concurred with the 1999

NFCS-SA findings, which showed that maternal education was

significantly associated with wasting and underweight in all groups

of children [26].

Approximately 92.2% of mothers were unemployed, which is higher compared to the national unemployment rate of almost 50%

and expanded the unemployment rate of 55.7% in Limpopo Province

and 51.6% in Greater Sekhukhune district [26]. Although most

(92.2%) of the mothers were unemployed, the official unemployment

rate, which is the rate of people who were actively looking for a job,

in the past four weeks prior to the study was 15%. This was lower

compared to the South African rate of 23.3% in 1999 [26].

Unsurprisingly, almost 91% of mothers had an income of less

than 500.00 ZAR per month and 33.9% of the households had a total

income of less than 1000.00 ZAR. Furthermore, maternal income was

significantly associated with stunting among children under the age

of 12 in the study area. Similar results were reported by Statistics SA

in 2005 and 2007, which showed that the majority (67%) of children in South Africa lived in households that had a monthly income of

1200.00 ZAR or less. Census 2011 showed that the average household

income was 45 977.00 ZAR [25]. These results clearly indicate that

most children lived in poor households because they lived below

the poverty line of approximately 8.00 ZAR (US $1) per person per

day, as stipulated by the World Bank. Shariff and Khor conducted a

similar study where demographic [28], socio-economic, expenditure,

and copying strategies were collected from 200 women of poor

households in Malaysia. They observed that most of the food insecure

(58%) was living below the poverty line.

The results of this study also showed that approximately 54% of

the households were financially supported by their grandparents.

This shows that the majority of households relied on pension grants as a source of income. These findings were contrary to the

findings that showed 31.25% of rural households relied on pension

as a source of income [29]. When applying the Statistics SA (2007)

recommendations of 431.00 ZAR per person per month, more than

77.3% of households were impoverished, especially taking into

consideration that more than 60% of households had 6 to 10 people

per household, this translates to 2586.00 ZAR to 4310.00 ZAR per

household per month [30].

Approximately 50.6 % of the households earned less than 1000.00

ZAR per month; this is high compared to 21% of urban households

who earned less than 1000.00 ZAR per month. This shows that the

geographic location has a close relationship with poverty, since the

wages of the employed people in rural areas tend to be too low to

support them and their families compared to urban households

[27]. The GSDM had a 77.3% rate of child poverty and only 25.5%

of children lived with employed parents, compared to a higher rate

(83%) of child poverty in Limpopo Province and only 28% of children

living with an employed parent/s [30].

Most households (75.6%) spent less than 500.00 ZAR per month

on purchasing food. The results are almost similar to findings from

Statistics SA, which showed that poorer households spent an average

of 200.00 ZAR per month on food, whilst the affluent spent 1350.00

ZAR on food, irrespective of the household size [31]. Thus, indicating

that the majority of households had low household income.

Household expenditure on food can be used as a proxy for household

income [32].

The current study showed that stunting was of high significance

for children below 60 months (39.6%). This high stunting prevalence

is likely to have serious consequences on child development, contrary

to a study by NFCHS [33], which showed an overall national, stunting

prevalence of 18% for children under 60 months. According to Dewey

and Begum there is growing evidence of the association between slow

growth in height early in life and impaired health [34], educational

and economic performance later in life. Trials in Guatemala indicated

that stunting can have long term effects on cognitive development,

school achievement, and economical productivity in adulthood and

maternal reproductive outcomes.

The current study indicated that approximately 84% of all the

children had normal weight-for-age. This implies that most children had normal weight. The study results concur with the findings by

Oldewage-Theron and Egal of a study conducted in the rural areas

of South Africa with a similar setting as that of the current study

[35]. However, approximately 11.1% and 3.9% of the children

were underweight and severely underweight respectively [35].

Furthermore, Kimani-Murage conducted a study among children

aged 1 to 14 years and revealed that the prevalence of underweight

in rural South African children was higher [36]. The difference in the

prevalence between the above-mentioned studies could have been

caused by the variation in the age group, and therefore a difference in

growth patterns would be expected.

The prevalence of wasting was low at 2.2% in children below

60 months. WHO concurs with our findings since it indicates that

provided there is no severe food shortage [37], the prevalence of

wasting is typically below 5%, even in poor countries. An equally

important fact is that approximately 57% of children in this study

group had normal weight-for-height, indicating that they were neither

under- nor over weight. The low prevalence of wasting was also found

in rural areas as reported by the SADHS 2016 and Schoeman et al.

[38]. They also reported a low (2.5%) prevalence of wasting and low

(1.3%) severe wasting [26]. However, Kimani-Murage showed a

medium prevalence of wasting at 7% for ages one to four years and 6%

for five to nine years old [34]. Remarkably, there was a 0% prevalence

of wasting in the 10 to 14 years of age category in the Kimani-Murage

study. Bhattacharya et al. indicated that nutritional outcomes among

school age children are not closely related to family resources [39].

Implying that the nutritional status of school going children might

be normal although the family is food insecure. This could be due to

children being able to supplement their food consumption at school,

friends, or at a neighbor’s home. In the case of South Africa, through

the school feeding programme.

The study findings reveal that 2.2% of children were overweight

whilst 8.9% were obese. Evidence now demonstrates that overweight

and obesity in childhood and adolescence have adverse consequences

on premature mortality and physical morbidity in adulthood [40].

The result of this study concurs with the study conducted by Kimani-

Murage [36], which showed low prevalence of overweight (7%) and

obesity (1%) respectively. In contrast, a study by Oldewage-Theron

and Egal showed a 17% prevalence of overweight and 4% obesity [34].

The head circumference for-age, computed only for children below three years of age, indicated that the majority of children had

normal brain growth/volume. Head circumference for age is also

used as a predictor of mortality, indicating that they were at the lowest

risk of mortality. Large head circumference has been associated with

conditions such as hydrocephalus and Autism Spectrum disorder,

while a small head circumference indicate microcephaly or poor brain

development which was not observed in this study population [41].

A study conducted by Bartholomeusz et al. indicated that there was

a close relationship between head circumference and brain volume

[42]. Moreover, head circumference for age is an excellent predictor

of brain volume in 1.7 to 6 years old.

The current study results are applicable to GSDM, which is

predominantly rural and underdeveloped and therefore cannot

be generalised to other areas. Measurements of socio-economic

parameters cannot rule out the possibility that the control for

socio-economic parameters was not complete (e.g. measurement of

household assets in order to determine wealth of each household).

The study only assessed the quality and not the quantity of foods

consumed. This is known to have an effect when measuring the socioeconomic

parameters such as food poverty and the nutritional status.

Conclusion

The determinants of stunting among children were

unemployment, poor purchasing power, and low household income.

Access to nutrient rich foods, health care, and nutritional health

knowledge could reduce the high prevalence of stunting among

children. In addition, empowering mothers with vocational skills

might reduce unemployment and increase the household income.

Acknowledgement

The project was funded by the South African National Research Foundation.