Journal of Neurology and Psychology

Download PDF

Research Article

High Levels of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness among Medical Students is Associated with Worst Quality of Life, and it is Higher among Female Students

Lima RP, Brenelli LM, Viana Miguel MA, Dias Pinto CC, Aprahamian I and Nunes PV*

Jundiai School of Medicine, Jundiai, Sao Paulo, Brazil

*Address for Correspondence: Nunes PV, Jundiai School of Medicine, rua Francisco Telles, 250, Jundiai, Sao Paulo, Brazil, Tel: +55 11 33952100; E-mail: paula@formato.com.br

Submission: December 14, 2019;

Accepted: January 30, 2020;

Published: February 04, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Lima RP, et al. This is an open access article

distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to analyze quality of life and excessive

daytime sleepiness of medical students and to correlate it with possible

conditioning factors such as gender, habits and year of attendance at

the Medical School.

Methods: The study was cross-sectional, using self-administered

questionnaires to all medical students. Questionnaires included

sample profile, the World Health Organization Quality of Life

assessment (WHOQOL-bref) and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS).

1.3. Results: The sample covered 266 students, 62% of which were

female. Excessive daytime sleepiness according to the ESS was found

in 66% of the sample. An inverse correlation of sleepiness and quality

of life was found (r=-0.338; p<0.001). Sleepiness was greater among

women (p=0.011), but had no correlation to the year of attendance

of the students. No differences were found in WHOQOL-bref total

score regarding gender or year of attendance. Students with healthier

habits, more specifically with regular physical activity and without

regular use of alcohol had higher scores on WHOQOL-bref total score

(p<0.001 and 0.015, respectively).

Conclusion: Excessive daytime sleepiness was present in a

considerable part of the medical students, especially amongst

women. Healthier habits and regular physical activity were associated

with greater quality of life. Future studies, prospectively collecting

information, could bring greater reliability concerning the impact

of the course would on quality of life and sleepiness, with special

emphasis on gender differences.

Keywords

Quality of life; Students; Medical; Education; Medical; Sleep deprivation; Stress; Psychological; Burnout

Introduction

During their course, undergraduate students of Medicine face

countless stress factors which can have serious consequences on

their health [1]. From the second half of the 20th century on, major

advances have occurred in different areas of Medicine, and each year

thousands of new publications are released. This makes university

courses complex, curricular contents extensive, and related workload

demanding. In search of good professional qualifications, students are

urged to tackle a series of supplementary activities such as research,

academic monitoring, internships, and other strenuous activities

they are subjected to, in terms of work hours and performance. In

addition, behaviors, skills, and mature attitudes are required from

students throughout their learning processes. Therefore, medical

career studies require impressive levels of dedication, from the highly

competitive entrance exams, through the graduation challenges,

to medical specialization which requires lengthy shifts, study and working hours [1]. Therefore, the academic overload faced by

medical student routines directly influences their quality of life.

The concept of quality of life is not new: Aristotle (384-322 BC)

described happiness as a virtuous activity of the soul, a final goal

that encompasses the totality of one´s life. Hippocrates (460-377

BC) asserted that balance provides a healthy body, which is directly

connected with the environment [2]. The idea also appears in ancient

Chinese philosophy, which defines that quality of life can be achieved

when the positive and negative forces, represented by the concepts

of Yin and Yang, are in balance. Thus, the concept has roots in both

Western and Eastern culture [2]. The term quality of life was used in

the United States after World War II for describing the acquisition

of goods. Later, this notion was extended in order to measure the

economic development of a society, comparing different regions

through economic indicators such as per capita income and gross

domestic product. Subsequently, the concept began to denote social

development through education, health, housing and transportation,

among other parameters [3]. Given the inherent complexity of the

definition of quality of life, in 1995 the World Health Organization

brought together experts from around the world and identified

quality of life as: “the individual’s perception of their position in life

in the context of culture and value systems in which they live and

in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” [4],

and six domains were identified: physical, psychological, level of

independence, social relations, environment and religious beliefs [4-6]. Quality of life has emerged as a new goal to be achieved, beyond

cure, control of diseases or the extension of life [7]. Too many activities

and requirements in Medicine courses prevent students from having

time to exercise, to take care of their health, to enjoy time with their

family and friends or to develop other interests, with impacts on their

quality of life. Stressful factors, such as great demands on learning, a

large amount of new information, lack of time for social activities and

coping with patients’ illnesses and sometimes deaths, may contribute

to the onset of depressive symptoms in students [8]. Some studies

have shown that medical students present average anxiety levels

above the overall population levels, and their depression scores can

increase during the first year of medical school [9,10]. Problems such

as substance abuse, self-mutilation and suicide were also reported

to be possible consequences of the routine of university students [11]. In this context, among the deleterious effects of the routine of

medical students, poor quality of sleep stands out. Medical students

constitute a group susceptible to sleep deprivation [12], a condition

that can directly affect their learning capacities, their health and their

quality of life. Students inserted in such an academic lifestyle often

end up altering their patterns of sleep-wake cycles [13], and they

hardly have any good sleep hygiene due to their habit of studying

or having leisure time at night, among other factors [14]. Attention

should be drawn to the fact that students, during the process of

learning the medical profession, often neglect themselves. The type

of medical learning process that leaves no room for reflection about

the human being inside the doctor undermines that professional’s

future [15]. Therefore, it is important to learn about quality of life of

these students in order to reduce stress levels and contribute to the

formation of better professionals, with impacts on the doctor-patient

relationship and with greater effectiveness and competence when

serving the population [16].

Hence, the present study aimed to analyze the quality of life and

excessive daytime sleepiness of undergraduate students from Jundiai

School of Medicine This study also aimed to correlate these variables

with possible conditioning factors such as gender, habits and year of

attendance.

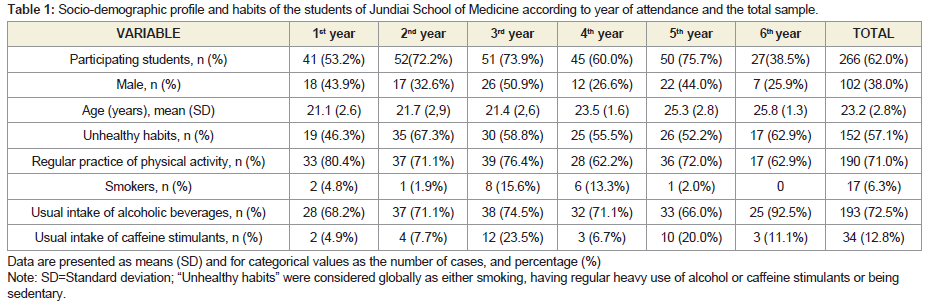

Table 1: Socio-demographic profile and habits of the students of Jundiai School of Medicine according to year of attendance and the total sample.

Materials and Methods

Subjects:

All Jundiai School of Medicine students were eligible to

participate. The Local Ethics Committee approved all procedures

before enrollment in the study.Design:

Cross-sectional descriptive study. The study sample consisted of

all undergraduate students of Jundiai School of Medicine, regularly

enrolled from the first to the last year of the medical course (6 years

total), who voluntarily wished to participate in the study and signed the informed consent form. Data collection was carried out during

regular academic activities, always in the beginning of the class period

in the same month. Students who refused to participate in the survey

were excluded from the study, as well as students who were absent on

the days of data collection.Measurements:

A self-administered questionnaire was provided by the same

applicants M.A.M and C.C.P., with information regarding: gender,

age, year of attendance and questions related to habits, physical

activity and eating patterns. To evaluate quality of life, the World

Health Organization Questionnaire for Quality of Life - Brief Form

(WHOQOL-bref), was used [6]. This questionnaire contains 26

questions, distributed in four domains: physical, psychological,

social and environmental relations. For the evaluation of daytime

sleepiness, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) was used [17]. The

ESS is a widely used scale and assesses excessive daytime sleepiness;

it contains eight situations such as the chance of napping while

sitting or reading, and napping while watching television, among

others. The score is marked by the student according to the following

instructions: 0 corresponds to “do not ever doze”; 1 corresponds

to “small chance of dozing”; 2 corresponds to “moderate chance of

dozing”; and 3 corresponds to “high chance of dozing”. The score

indicated by the student in all situations investigated is summed up.

Overall scores from zero to nine points indicate absence of sleepiness;

scores from 10 and 16 points indicate mild sleepiness; scores from 17

to 20 points indicate moderate sleepiness; scores from 21 to 24 points

indicate severe somnolence [17]. For all instruments, language used

was Brazilian Portuguese.Statistical analysis:

For continuous variables normality was tested using the

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. To compare participants among

the groups, we used independent samples Student’s T-test for

quantitative variables (as normality was attended), and chi-square test

for categorical variables followed by One Way ANOVA to evaluate

potential influence of year of attendance, sex, healthy habits, physical

activity, alcohol and stimulants use. For correlations, the Sperman’s

correlation test was used. The level of significance was set at 0.05. The

software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version

20.0 was used to perform statistical analyses.Results

The sample included 266 medical students (62.0% of attending

students).Their average age was 23.2±2.8 years old, and 62% were

female. Among these students, 71% declared themselves to be regular

practitioners of physical activity, 6.3% were smokers, 72.5% made

regular use of alcoholic beverages, 57% considered their health habits

unhealthy and 12.8% referred using caffeine stimulants regularly

(Table 1).

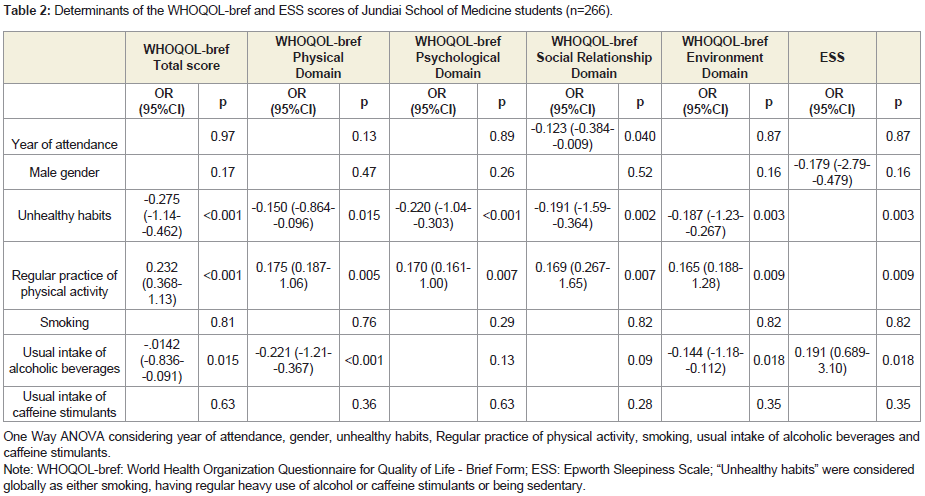

According to the ESS, excessive daytime sleepiness (scores above

9) was found in 66% of the students, and 14% of the students had

moderate to severe sleepiness (scores above 16). There was a negative

correlation of ESS and WHOQOL-bref total (r=-0.338; p<0.001), that

is, the greatest the daytime sleepiness, the worst the quality of life.

Similar results were found for each of the WHOQOL-bref domains: physical (r=-0.395; p<0.001), psychological (r=-0.179; p=0.003),

social relationships (r=-0.129; p=0.035), and environment (r=-0.247;

p<0.001). ESS scores were greater among women (p=0.006)and

amongst those that stated having regular use of alcoholic beverages

(p=0.002) (Table 2). No difference was found according to year of

attendance and other habits for the ESS scores. No difference was

found in WHOQOL-bref total score regarding year of attendance

and gender. WHOQOL-breftotal score was lower in students that

considered themselves as having unhealthy habits (considered

globally as either smoking, having regular heavy use of alcohol or

caffeine stimulants or being sedentary)(p<0.001). More specifically,

WHOQOL-breftotal score was lower in those having regular use of

alcohol (0.015) and greater in those who practiced regular physical

activity (p<0.001). Similar results were found for the relationship

of the WHOQOL-bref domains (physical, psychological, social

relationships and environment) with gender, unhealthy habits,

practice of physical activity, smoking, and for usual intake of

caffeine stimulants. No relationship was found for WHOQOL-bref

psychological and social relationships domains and usual intake

of alcoholic beverages, but it was found for the physical domain

(p<0.001) - an inverse relationship, similarly to the total score. Finally,

in the social relationships domain there was a difference according to

the attending year (p=0.004), with decreasing values from the first

year to the last year. Students that considered that their eating habits

got worse after they started attending medical school had lower scores

on WHOQOL-bref total score (p=0.018), but no difference was found

in ESS scores.

Discussion

Students of Jundiai School of Medicine had high prevalence of

inappropriate sleepiness, reported by 66% of the sample. There was a

significant difference between genders, with higher sleepiness scores

among women. No differences were found according to year of

attendance. There was an inverse correlation between inappropriate

daytime sleepiness and quality of life specially its physical and

environment domains. On the other hand, students with healthier

habits and with regular physical activity had better quality of life.

Finally, there were a few differences in WHOQOL-bref social

relationships domain among the years, with decreasing values from

the first to the last years. The WHOQOL is a widely used instrument in

scientific research. In a 2010 cross-sectional study carried out with 370

medical students from the city of Recife in Brazil, there was a decrease

in the WHOQOL-bref psychological domain among students closer

to concluding their medical course, when compared to students

beginning it [10]. In the present study, however, a trend was found only

in the social relationships domain. In this sample of medical students,

71%reported to practice regular physical activity. The inclusion of

physical activity in the curriculum of Jundiai School of Medicine in

the first two years of the course, as well as related facilities provided,

allowing training of various modalities, might have had an impact on

that percentage. Since regular physical activity was related to higher

WHOQOL-bref scores (p<0.001), the habit of regularly practicing

physical activities could contribute to maintaining WHOQOL-bref

scores even in those difficult last years of the course. However, this

hypothesis was not tested due to the cross-sectional design of the

present study. The correlation of physical activities with quality of

life in our study is in agreement with the literature. In a systematic review, higher levels of physical activity were associated with better

perception of quality of life both in healthy adults and in individuals

with different health conditions [18]. Similarly, in a study in Brazil,

active individuals had higher WHOQOL-bref scores in the physical,

psychological and environmental domains [19]. Intervention studies

with a high number of participants (n=1089) during 12 months and

extended for 12 more months also pointed to similar results, with

improvement in quality of life in the intervention group [20]. When

considering the several factors potentially associated with quality of

life, it was also verified that students who stated more healthy habits

presented higher scores in the WHOQOL-bref scores compared to

those who affirmed inappropriate habits (p<0.001). Based on the

definition of the World Health Organization, that quality of life is

“the individual’s perception of their position in life, in the context

of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation

to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” [5], this data

could be considered one possible evidence of the reliability of the

instrument used to measure quality of life among medical students,

as it uses the individuals own perception on their reality.

The present study shows, through ESS, inappropriate daytime

sleepiness in 66% the students of Jundiai School of Medicine, far above

the average of epidemiological studies in Brazilians. As an illustration,

studies in adult populations the prevalence of inappropriate daytime

sleepiness was 22% [21], and 19% [22]. Our results of high prevalence of inappropriate daytime sleepiness are in accordance with other studies with medical students. Excessive daytime sleepiness in was found in 52% of 276 students (academics and residents) and

the average scores in the ESS were 11 [12]. In all attendance years

the levels of sleepiness were high, on average above the cutoff of 9,

without differences amongst the years. One possible explanation for

that could be that different factors contributed to sleepiness across the

years. Concerning the genders, in our study women presented higher

levels of daytime sleepiness (p=0.011).

Once our population of students is young (23 years, on average) it

could be hypothesized that the high rates of excessive daytime sleepiness

observed could be due to be sleep deprivation. As contributing factor

for that, we can mention extensive workload of the medical course,

with full-time activities and night shifts, extracurricular activities, a

high requirement for study, preference of night hours for leisure time

and others. It is also noted that sleep deprivation in medical students,

internship students and even physicians is often seen as inherent in the

profession itself, or even as a symbol of dedication to the profession.

It is known, however, that sleep is a fundamental biological function

in the consolidation of memory and learning, binocular vision,

thermoregulation, conservation and restoration of energy and of the

energy metabolism [23]. For such processes to occur, however, there

must be a good sleep quality [24]. People who sleep poorly tend to

have more morbidities, shorter life expectancy and premature aging

[25]. In addition, in sleep deprivation, symptoms such as malaise,

irritation, fatigue, impaired agility and mental efficiency can be

observed. Excessive daytime sleepiness can affect the performance

of most of the individual’s cognitive domains in the long or short

term, resulting in impairment of attention, concentration and

operational memory [26]. Sleep deprivation in medical students, may

momentarily increase productivity in both studies and care. However,

it can lead to decreased productivity, cognitive deficits, as well as to precipitate some psychiatric disorders. Therefore, sleep deprivation

can compromise general health and quality of life [24]. Among

the implications on cognitive performance is the increase in errors

in activities that demand attention [27], which can translate into a

risk imposed on the medical students themselves, the individuals in

their immediate learning environment, and the patients cared for.

Therefore, the present study reaffirms the possible impact of sleep

impairment on quality of life through the inverse correlation between

scores obtained through the WHOQOL-bref and ESS(r = -0.338).

As complementary observations, a minority of the students

(6.3%) reported the use of tobacco, but a considerable portion

(72.5%) made customary use of alcoholic beverages. These data are

in line with other studies that evidence alcohol abuse among health

students [28-30].

The present study has several limitations that should be taken into

account. Some students did not participate, especially in the last years

of the course. This was due to difficulties in data collection, especially

with regards to students in the last two years of the course that have

activities at different times and places. Another important limitation

is the cross-sectional nature of the study. We used a validated

Brazilian Portuguese version of the questionnaires the World Health

Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL-bref) and the

Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). For other variables such as gender,

year of attendance, regular physical activities, smoking, regular use of

alcoholic beverages or stimulants and “unhealthy habits” we did not

use a validated scale and therefore the results of these variables should

be interpreted taking into consideration these limitations. Future

studies, prospectively collecting information, could bring greater

reliability concerning the impact of the course would on quality of

life and sleepiness, with special emphasis on gender differences for

sleepiness that was evidenced in our study. Other variables that could

influence quality of life and sleepiness, such as affective disorders and

cognitive deficits, as well as sleeping and food habits could be also

more thoroughly explored in future studies.

Finally, continuing studies which may contribute with data

on the reality of medical students should be granted. Such studies

may direct faculties to seek strategies for both curricular reforms

and intervention programs in the physical, mental health and sleep

hygiene of students, as well as to opening space for discussion on

the subject as well as raising students’ awareness of the subject.

Such measures can minimize the wear and tear suffered before the

diploma. It is worth highlighting intervention studies with positive

results on psychological distress and quality of life [31]. Among

coping strategies, valuing interpersonal relationships and everyday

phenomena, balancing between study and leisure, organizing time,

health care, s and sleep, practicing physical activity, religiosity,

working the personality itself to deal with adverse situations and

seeking psychological assistance should be investigated as potential

sources for improvements in quality of life [16].

The earlier the medical student reflects on his own life and quality

of life, the better the student can contribute to the quality of life of

patients. Furthermore, the medical school must have this concern,

both in the elaboration of its curricular plan and in promoting

psychological and pedagogical support for the student to deal with

needs in academic and professional life.