Journal of Neurology and Psychology

Download PDF

Research Article

Astrocyte Activation is A Potential Mechanism Underlying Depressed Mood and Apathy in People with HIV

Ronald J. Ellis1*, Yan Fan2, David Grelotti3, Bin Tang3, Scott Letendre4 and Johnny J. He5

1Departments of Neurosciences and Psychiatry, University of

California, San Diego, CA, United States

2Department of Ophthalmology, UT Southwestern Medical Center,

Dallas TX, United States

3Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, CA,

United States

4Departments of Medicine and Psychiatry, University of California,

San Diego, CA, United States

5Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Chicago Medical

School Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, IL, United

States

*Address for Correspondence: Ronald J. Ellis, UCSD HNRC, 220 Dickinson Street Mail Code 8231, Suite B

San Diego CA 92103-8231 E-mail: roellis@health.ucsd.edu

Submission: November 18, 2022

Accepted: December 20, 2022

Published: December 26, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Ellis RJ, et al. This is an open access article

distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background: Astrocytes become activated with certain

infections, and this might alter the brain to trigger or worsen depressed

mood. Indeed, astrocytes are chronically activated in people with

HIV infection (PWH), who are much more frequently depressed than

people without HIV (PWoH). A particularly disabling component of

depression in PWH is apathy, a loss of interest, motivation, emotion,

and goal-directed behavior. We tested the hypothesis that depression

and apathy in PWH would be associated with higher levels of a

biomarker of astrocyte activation, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP),

in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Methods: We evaluated PWH in a prospective observational

study using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and additional

standardized assessments, including lumbar puncture. We measured

GFAP in CSF with a customized direct sandwich ELISA method. Data

were analyzed using ANOVA and multivariable regression.

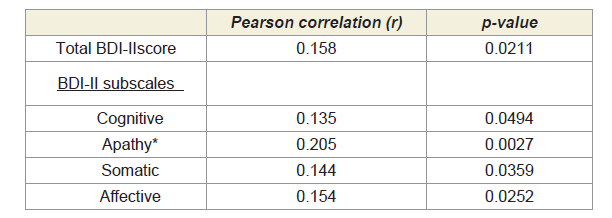

Results: Participants were 212 PWH, mean (SD) age 40.9±9.14

years, median (IQR) nadir and current CD4 199 (57, 326) and 411

(259, 579), 65.1% on ART, 67.3% virally suppressed. Higher CSF GFAP

correlated with worse total BDI-II total scores (Pearson correlation

r=0.158, p-value=0.0211), and with worse apathy scores (r=0.205,

p=0.0027). The correlation between apathy/depression and GFAP was

not influenced by other factors such as age or HIV suppression status.

Conclusions: Astrocyte activation, reflected in higher levels of

CSF GFAP, was associated with worse depression and apathy in PWH.

Interventions to reduce astrocyte activation -- for example, using a

peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonist -- might be studied to evaluate

their impact on disabling depression in PWH.

Introduction

Despite viral suppression on combination antiretroviral therapy

(ART), people with HIV (PWH) suffer from a higher prevalence

of depression than the general population. Depression is the most

common psychiatric comorbidity in HIV [1] and apathy – a lack

of interest, motivation, emotion, and goal-directed behavior – is a

particularly prominent and frequent manifestation of depression

in PWH [4]. While often related to depression, apathy also occurs

in other brain disorders where dopaminergic neurotransmission

is disrupted, such as abulia and akinetic mutism. Dopaminergic

dysfunction is also common in PWH [5]. PWH who have depression

and apathy show poorer medication adherence [6], lower rates

of viral suppression [7,8] poorer quality of life [9,10], and shorter

survival [11-14]. Chronic systemic and neuro-inflammation persist

in virally suppressed PWH and predict morbidity and mortality

[15]. Apathy and anhedonia are linked to inflammation [16] as

evidenced by elevated levels of interleukin-(IL-)6 and tumor necrosis

factor (TNF)-α [17-22]. Inflammation, anhedonia, and apathy often

signal resistance to traditional antidepressants [23-29]. In the brain,

activated astrocytes mediate many aspects of immune function and

inflammation. Astrocyte activation is an important contributor to neuronal-glial network dysfunction in depression [30,31], as

would be expected based on the central role of astrocytes in brain

metabolism and inflammatory signaling. Astrocyte activation at

autopsy is associated with antemortem depressed mood [32,33].

Expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) is upregulated

in activated astrocytes [34], and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels

of GFAP, a marker of astrocyte activation, are increased in people

with depression [35]. Astrocyte activation is a prominent feature of

brain disease in HIV and correlates with the release of neurotoxicviral

proteins such as Tat [36-41]. Although apathy is a particularly

prominent and disabling component of depression in PWH and

HIV causes astrocyte activation, no previous study has evaluated

CSF GFAP levels in PWH in the setting of depression and apathy .

We tested the hypothesis that elevated CSF GFAP levels, reflecting

astrocyte activation, would be correlated with depressed mood and

apathy in PWH.

Methods

This cross-sectional study evaluated PWH at 6 US centers in

CNS AntiRetroviral Effects Research (CHARTER), a prospective

longitudinal cohort, between 2003-2008. Inclusion criteria were

HIV seropositivity and ability to complete the protocol. Participants

who had severe neuropsychiatric comorbidities (e.g., untreated

schizophrenia or seizure disorder) were excluded. All study

procedures were approved by local Institutional Review Boards and

all participants provided written informed consent for the study

procedures, including future use of data and biospecimens.

All participants were comprehensively evaluated with

standardized assessments including lumbar puncture, phlebotomy,

neuromedical history and examination, and laboratory testing. A trained clinical examiner interviewed and examined participants to

collect information such as antiretroviral treatments, nadir CD4+ T

cell counts, and history of diabetes mellitus.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression

Inventory (BDI-II), a validated survey of 21 questions that assess

depressive symptoms and their severity [42]. Higher BDI values

indicate higher severity depressive symptoms with a value >13

indicating at least mild depression. The BDI-II includes three standard

subscales capturing cognitive, somatic, and affective symptoms

of depression. Since we predicted that the apathy component

of depressed mood would be particularly important in HIV, we

constructed an apathy subscale using items that specifically address

apathy symptoms: loss of pleasure, loss of interest, indecisiveness,

and tiredness or fatigue (range 0-5, higher scores indicate worse

atrophy).Dependence in instrumental activities of daily living

(IADLs) was assessed using a modified version of the Lawton and

Brody Scale [43] that asks participants to rate their current and best

lifetime levels of independence for 13 major IADLs such as shopping,

financial management, transportation, and medication management

[9]. Individuals who reported difficulties in completing >2 IADLs

were considered functionally dependent.

Clinical Laboratory Evaluations:

HIV infection was diagnosed using an enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay with Western blot confirmation. HIV RNA

in plasma was measured using commercial assays and deemed

undetectable at a lower limit of quantification (LLQ) of 50 copies/mL.

CD4+ T lymphocytes were measured by flow cytometry and nadir

CD4+ T lymphocyte count was assessed by self-report.CSF GFAP in picograms per milliliter (pg/mL)was measured

by a customized direct sandwich ELISA method, with a mouse

monoclonal antibody cocktail against GFAP (Covance, Cat#SM1-

26R) as the capturing antibody and a rabbit polyclonal anti-

GFAP antibody (DAKO, Cat# Z0334) as the detection antibody.

GFAP protein standards (Calbiochem, Cat# 345996) were used to

standardize concentration curves.

Statistical Analyses:

Demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized using

means and standard deviations, medians, and interquartile ranges

or percentages, as appropriate. Log10 transformation was used to

normalize CSF GFAP values. The Pearson correlation coefficient

was used to measure the relationship of GFAPlevels to indices

of depressed mood and apathy. We applied ANOVA when the

distribution of the outcome variable was not significantly different

from normal. When distributions significantly deviated from normal,

non-parametric analyses were conducted. Follow-up analyses used

recursive partitioning to identify informative GFAP cut-offs. We

adjusted for testing multiple related outcomes using the Benjamini

Hochberg procedure. When potential statistically confounding

variables such as age and demographic and disease variables were

significantly related to both the predictor (CSF GFAP level) and

outcomes of interest (apathy, depression), we evaluated these further

in multivariable regression analyses. Relevant covariates considered

included demographics, HIV disease and treatment parameters, and

antidepressant treatments. Analyses were conducted using JMP Pro version 15.0.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, 2018).Results

The sample included 212 participants with a mean±SD age

40.9±9.14 years, female17.9%, black40.6%, non-Hispanic white

47.6%,Hispanic 8.96%, other race/ethnicity 2.83%, non-Hispanic

white 47.6%, median (IQR) duration of HIV infection 7.3 (2.58,

12.8) years, current CD4 411 (259, 579), nadir CD4199 (57, 326),

plasma HIV RNA suppressed (<50 copies/mL) in32.7%, CSF HIV

RNA suppressed in 62.3%. The mean±

SD log10 CSF GFAP level was

3.47±0.0781pg/mL, and the mean BDI-II score was 12.2±9.84, with

39.2% having a BDI-II>13, reflecting at least mild depression.

Potential statistical confounds:

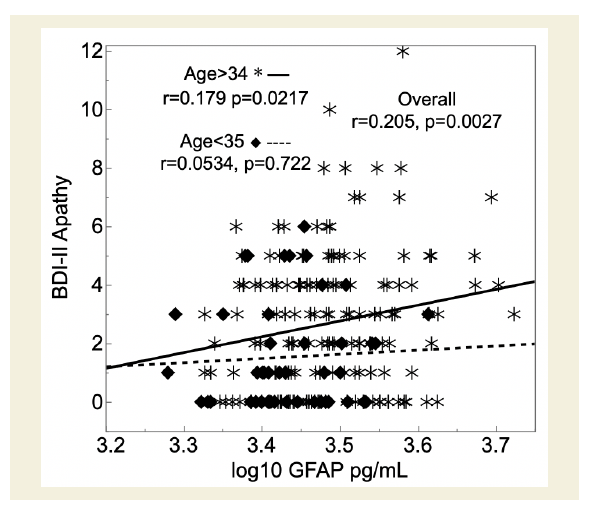

Demographics Several variables were significantly related to

depression parameters and GFAP levels. Older individuals had both

worse apathy (r=0.220, p=0.0013) and higher log10CSF GFAP (r=0.357,

p=9.00e-8). In a multivariable regression predicting apathy scores,

the interaction between age and GFAP was not significant(p=0.888),

while both main effects of both GFAP (p=0.0442) and age (p=0.0197)

were significant. Apathy scores were not related to sex or ethnicity.

Older PWH also had worse overall depressed mood (BDI-II total

score; r=0.155, p=0.0305). In a multivariable regression predicting

BDI-II total score, the main effect of age (p=0.164) and the interaction

of age with GFAP (p=0.846) were not significant.Sex and ethnicity were not significantly related to BDI-II total

score. However, both sex and ethnicity were related to CSF GFAP.

Males had higher GFAP levels than females (mean±SD 3.48±0.0793

versus 3.44±0.0635, p=0.0033) and whites had higher levels than the

other ethnicities (non-Hispanic white [3.49±0.081] versus [black,

3.46±0.076] versus Hispanic [3.44±0.060] versus other race/ethnicities

[3.450.031]; p=0.0051). In a multivariable regression predicting BDIII

total score, GFAP was statistically significant (p=0.0165), while sex

and the interaction term were not(ps>0.25).In a similar regression for

ethnicity, GFAP was significant (0.0239), while ethnicity(p=0.237)

and the interaction (p=0.891) were not.

Antidepressant medications The proportion of participants

taking antidepressant medications was 32%. The odds of taking

antidepressants for those with a BDI-II>13 was 2.50 (95% confidence

interval 1.38, 4.54). Antidepressant use was associated with worse

apathy scores (3.45±2.34 versus 1.94±2.11, p=5.43e-6) and higher

GFAP levels (3.46±0.0789 versus 3.50±0.0706, p=0.0003).PWH

both on and off antidepressant medications contributed to the

relationship between GFAP and apathy: for those on at least one

antidepressant: r=0.123, p=0.295, N=67; for those not on any

antidepressants: r=0.139, p=0.0988, N=142;interaction p=0.895.

Laboratory Parameters PWH with detectable plasma viral

loads had worse total BDI-II scores (13.2±9.93 versus 10.2±9.43,

p=0.0409)as well as worse scores on the cognitive (4.82±4.76 versus

2.94±3.86, p=0.0049), but not apathy, somatic or affective items

(ps=0.0990, 0.3893 and 0.0856, respectively). Both virally suppressed

and unsuppressed PWH contributed to the relationship between

GFAP and apathy: for suppressed PWH r=0.126, p=0.302, N=69;

for not suppressed r=0.262, p=0.0016, N=142; interaction p=0.388.

Detectable viral load was not associated with CSF GFAP(3.47±0.0797 versus 3.48±0.0748, p=0.160). In a multivariable regression

predicting BDI-II cognitive scores, the main effects of both GFAP

(p=0.00139) and detectable viral load were significant (p=0.00316),

but their interaction was not (p=0.438). Findings were similar for

the BDI-II total score (data not shown). Those with suppressed CSF

HIV RNA had better apathy scores (2.17±2.26 versus 2.85±2.29,

p=0.0347). Higher GFAP correlated with higher CSF total protein

(r=0.310, p=4.51e-6), but CSF protein did not relate to apathy scores

(r=0.092, p=0.183). GFAP was not influenced by CSF leukocyte count

(r=-0.0136, p=0.845). Apathy scores did not correlate with current

(r=0.0353, p=0.610) or nadir CD4+ T cells (r=0.00936, p=0.893), or

plasma viral suppression (suppressed 2.058±2.60 versus unsuppressed

2.61±2.99, p=0.0990) (Table 1).

Table 1: Higher CSF GFAP levels (greater astrocyte activation) correlated with

worse Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) total and subscale scores (higher =

worse depression).

In a multivariable regression predicting BDI-II, GFAP was

significant while being on an antidepressant and its interaction with

GFAP were not (ps=0.153 and 0.359). In a stepwise multivariable

regression (p to enter 0.05, p to leave 0.05) predicting BDI-II total

score from CSF GFAP, age, sex, ethnicity, nadir, and current CD4+

T-cell count and viral suppression, the model selected CSF GFAP

(p=0.00915) and lack of viral suppression(p=0.00998) as the best

correlates (overall model p=0.0046).

Impact of Depression on Activities of Daily Living and Quality of Life: PWH with worse depression (higher BDI-II scores) had worse

HIV-MOS physical health summary scores (r=-0.626, p=1.85e-23),

and worse mental health summary scores (r=-0.825, p=1.25e-51).

Similarly, higher CSF GFAP correlated with worse physical (r=-0.177,

p=0.0116)and mental (-0.196, 0.0052) health scores. The proportion of

participants reporting dependence in instrumental activities of daily

living (IADLs) was 15.6%; participants with a BDI-II>13 had 11.9-

fold higher odds of being dependent (95% CI 4.68, 36.8; p=1.57e-8).

There was a 3% increase in the odds of having detectable plasma viral

load per one-unit increase in BDI-II scores increased (OR 1.03 [95%

CI 1.00, 1.07] per 1-point increase in BDI-II,p=0.0372). Similarly,

the odds of having detectable CSF viral load increased as BDI-II

scores increased (OR 1.03 [1.01, 1.06] per 1-unit increase in BDI-II,

p=0.0194).

Discussion

This is the first study to show that PWH with worse apathy and

other attributes of depressed mood had higher levels of GFAP in CSF.

Since in the central nervous system GFAP is found only in astrocytes,

and since its expression is upregulated in activated astrocytes [34],

higher CSF GFAP concentrations are believed to reflect greater

astrocyte activation. Astrocytes are known to be activated in HIV

infection [36-41] and to influence brain circuits involved in mood

and motivation [30,31,35]. This study’s principal finding that

depression in PWH was associated with higher CSF GFAP levels was

robust to consideration of a variety of important demographic and

disease-related potential confounds. Our data are consistent with

previous research on the role of astrocyte activation in depression

in PWoH [30,31] and extend these findings to PWH.Consistent

with the existing literature [44], worse depressed mood in this study

was associated with several adverse outcomes including poorer viral

suppression and independence in instrumental activities of daily

living, highlighting the clinical impact of depressed mood in PWH (Figure 1).

Figure 1: PWH with higher levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in

cerebrospinal fluid (CSF; x-axis) had worse BDI-II apathy subscale scores

(y-axis). This relationship was significant for those older than 34 years

(asterisks), but not for younger participants (diamonds).

We suggest that the impact of astrocyte activation on depression

is via neurotoxicity [37]. Astrocytes, among other functions, are

responsible for metabolic support to neurons [45,46] and are involved

in neuronal repair [47]; activation of astrocytes diverts their resources

from neuronal support. Astrocyte activation related to HIV infection

may confer greater vulnerability to depression in PWH, a biological

risk factor that may explain the higher prevalence of depression in

PWH.

Strengths of this work include the careful characterization

of depressed mood and the consideration of a range of potential

confounding factors, to which the primary findings were robust.

The cohort was multicenter and racially diverse, enhancing

generalizability. Limitations of this study include its cross-sectional

design, limiting causal inference. Based on existing knowledge, a

causal link between astrocyte activation, as indexed by CSF GFAP,

and depressed mood is plausible; however, it is conceivable that

changes in activity, diet and other lifestyle factors associated with

depression might lead to astrocyte activation (reverse causation).

Statistical confounds were not detected in this study; however, an unmeasured variable might account for the association between

GFAP and depressed mood. The effect sizes demonstrated here were

small, albeit statistically significant. Females were underrepresented.

The rate of viral suppression was lower than in many modern cohorts;

however, after adjustment for viral suppression, elevated CSF GFAP

levels were still significantly associated with depressed mood.

Antidepressant medications could have been taken for reasons other

than depressed mood, such as for neuropathic pain.

These findings raise the possibility of interventions, potentially

influencing pathways that might affect depressed mood [48-51]. For

example, using a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonist

[52,53] or the synthetic cannabinoid R(+)WIN 55,212-2, both of

which inhibit astrocyte activation [31,48]. A future clinical trial

may fruitfully explore this therapeutic option for depressed PWH,

particularly those who fail to respond to traditional antidepressant

treatments.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants R01MH092673 (J. He), R01MH107345 (PIs

Heaton and Letendre), and R24MH129166 (PIs Letendre and Ellis)

from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States.

The CNS HIV Anti-Retroviral Therapy Effects Research

(CHARTER) group is affiliated with Johns Hopkins University; the

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; University of California,

San Diego; University of Texas, Galveston; University of Washington,

Seattle; Washington University, St. Louis; and is headquartered at

the University of California, San Diego and includes: Directors:

Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D., Scott L. Letendre, M.D.; Center Manager:

Donald Franklin, Jr.; Coordinating Center: Brookie Best, Pharm.D.,

Debra Cookson, M.P.H, Clint Cushman, Matthew Dawson, Ronald

J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., Christine Fennema Notestine, Ph.D., Sara

Gianella Weibel, M.D., Igor Grant, M.D., Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D.

Jennifer Marquie-Beck, M.P.H., Florin Vaida, Ph.D.; Johns Hopkins

University Site: Ned Sacktor, M.D. (P.I.), Vincent Rogalski; Icahn

School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Site: Susan Morgello, M.D. (P.I.),

Letty Mintz, N.P.; University of California, San Diego Site: J. Allen

McCutchan, M.D. (P.I.); University of Washington, Seattle Site: Ann

Collier, M.D. (Co-P.I.) and Christina Marra, M.D. (Co-P.I.), Sher

Storey, PA-C.; University of Texas, Galveston Site: Benjamin Gelman,

M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), Eleanor Head, R.N., B.S.N.; and Washington

University, St. Louis Site: David B Clifford, M.D. (P.I.), Mengesha

Teshome, M.D.The views expressed in this article are those of the

authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United

States Government.