Journal of Neurology and Psychology

Download PDF

Research Article

Humour, Mirth, or Laughter in Neurology, Nervous Disorders and Diseases

Venkatesan S1*, Ranganatha PR2, Yashodhara Kumar GY3 and Lancy D’Souza4

*Address for Correspondence: S. Venkatesan, Formerly Dean-Research, Professor & Head, Department

of Clinical Psychology, All India Institute of Speech & Hearing, Manasagangotri, Mysore: 570006, Karnataka, India, Email: psyconindia@gmail.com

Submission: October 16, 2022

Accepted: May 08, 2023

Published: May 12, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Venkatesan S, et al. This is an open access article

distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Pathological Laughter; Brain-Behaviour; Therapeutic Humour;

Gelatology

Abstract

The available research on humor, mirth, or laughter in neurology,

nervous disorders, and diseases is sparse and fragmented. This review

attempts to collect, collate, and evaluate available evidence

afresh in this research paper. Although descriptive, the included

literature covers around eighty peer-reviewed published articles

written exclusively on the chosen theme. The anatomical, organic,

evolutionary, and functional basis is delineated before specific

neurological disease conditions are invoked to understand how

humor is believed to be generated, appreciated, or can be even

used as an adjunct form of therapy to ameliorate these conditions. The

opportunities and challenges for humor research in the contemporary

scenario for neurology are summarized with a plea for more empirical

work in this direction.

Introduction

This descriptive review highlights the humor-laughter found in

keyword searches of published works on neurological diseases and

disorders. The terms “disease” and “disorder” are used interchangeably

in everyday speech. A disorder is explained as a disruption to the

usual bodily functions. A disease is defined as the pathological

response of the body to external or internal factors that disrupted

body functions. Disorders can be physical, mental, structural, genetic,

behavioural, or emotional (Cooper, 2004) [1]. Reviews from this

same published source have covered introductory topics on theories

and developmental aspects of humor applied to children, the elderly,

and persons with disabilities-impairments [2a,2b

].

Method

From a database of over 900 entries covering all categories of

humor currently available to the author, this narrative examines

nearly 80 peer-reviewed research articles on the theme. The entries

were compiled based on a thorough examination of online secondary

data sources as enumerated after keyword searches of terms like

those in the title of this article. Both offline/online searches with

standard publication identifiers were compiled, coded, categorized,

and classified by title, theme, year, and names of author/s or journals.

Search engines included Google Scholar, JSTOR, PUBMED,

PsycINFO, ERIC, and the Web of Science until March 31, 2023.

Newsletters, periodicals, in-house magazines, proceedings of

seminars, webinars, or conferences, mimeographs, video or audio

materials, and unpublished pre-doctoral doctoral or post-doctoral

dissertations were excluded. Incomplete, misleading, repeated, and

unverified cross references from available full text articles and books

were also excluded.

Two independent coders who were mutually blinded were used to conduct inter-observer reliability assessments on at least 25% of the entries in the entire sample.

The official mandate’s ethical guidelines were strictly observed [3].Using SPSS/PC, a descriptive and interpretive statistical analysis was conducted [4]. [5]recommendations were used to analyse effect sizes

The official mandate’s ethical guidelines were strictly observed [3].Using SPSS/PC, a descriptive and interpretive statistical analysis was conducted [4]. [5]recommendations were used to analyse effect sizes

Results

The collected information on references to humour, mirth, or

laughter in neurology, nervous disorders, and diseases was organized

into a harvest plot according to their publication dates, decade of

publication, and format (books, book chapters, original research

articles based on experimental, observational, or empirical data,

reviews, or essays).

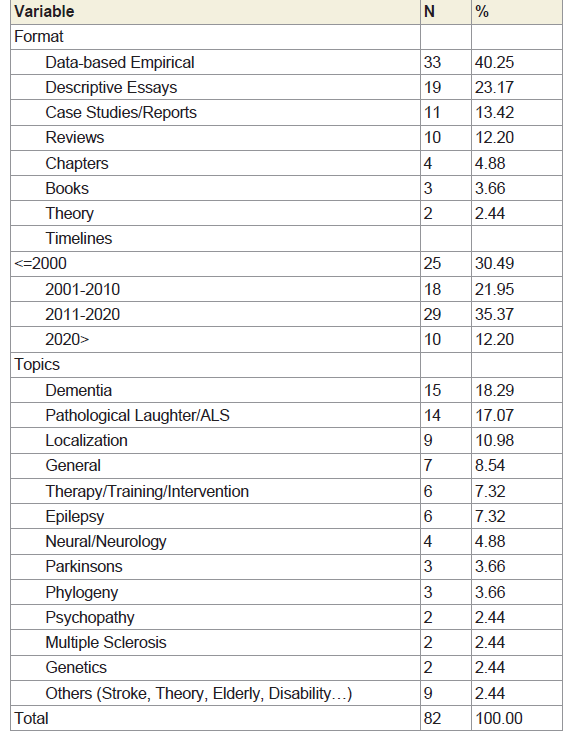

Format:

The majority of the publications included in this compilation (N

= 33;40.25%) are data-based empirical research papers, followed by

descriptive essays (N= 19;21.17%),case studies or reports (N = 11;

13.42%), reviews (N = 10;12.20%), and so forth. There aren’t many

published books or book chapters that focus solely on humor in

neurology, nerve disorders, and diseases. As of yet, there is no grand

theory explaining this.Timelines:

Based on timelines in the enlisted database, the earliest available

publication is a general essay on aphonogelia-a rare neurological

symptom characterized by the inability to laugh audibly [6]. Another

early genetic study on laughter-provoking stimuli debated whether

humor is innate or acquired [7]. Other publications of the 1930s are

descriptive essays/case reports of brain-damaged patients showing

Table 1: Harvest plot showing the frequency distribution of compiled literature on

humor, mirth, or laughter in neurology, nervous disorders and diseases.

pathological laughing and crying [8,9].The first experimental inquiry

in this bibliography on neurology-linked themes targets righthemisphere-

damaged patients. The finding is that surprise-not,

coherence is the basis for humor in such brain-damaged persons [10].

This is followed by another book chapter carrying a short narrative on

the neuropsychological perspective of humour [11].

Later explorations covered the biological basis or correlate,

including genetic, evolutionary, anatomical, endocrine, and

physiology of humor [12-15]. Smiling and laughter are not unique

to humans. The cerebral organization of laughter has been studied

from the evolutionary perspective in squirrel monkeys, apes, gorillas,

bonobos, orangutans and juvenile chimpanzees [16].wherein playful

tickling and biting evoke laughter described as part of the false alarm

theory in the neurology and evolution of humor [17]. Human infants

are also noticed to smile in the first five weeks of extrauterine life.

Laughter emerges later by about four months. About 16 different

types of smiles are detected, such as scornful, mocking, social, or

faked, as part of infant face recognition [18].

Early attempts to review, collate, and evaluate studies from the

fragmented evidence on the neurology of mirth, laughter, and humor

have implicated the frontal cortex, the medial ventral prefrontal cortex,

the right and left posterior (middle and inferior) temporal regions,

and possibly the cerebellum to varying degrees [19,20]. A consensus

based on neuropsychology approaches is that humor is essentially a right hemisphere function, as evidenced consistently by the loss of

appreciation for sarcasm by studies of brain damage in those areas

[21-24]. As part of the limbic system, the amygdala and hippocampus

are implicated in the human brain in the production of laughter [25].

Disease or damage to these areas is recorded as testimonies of the

resulting pathological crying and laughter [26] failure to distinguish

lies from jokes [24] .loss of sensitivity to verbal humor [10]. As shown

in cases of traumatic brain injury [27]. Similarly, gelatophobics

showed greater activation than non-gelatophobics in the areas of the

dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in response to hostile and non-hostile

jokes, thereby hinting at the neural correlates of humor appreciation

[28].

Ablation studies have shown how basic levels of cognition but not

necessarily one’s sense of humor are affected [29]. Anecdotal reports

of survivors with agenesis of the corpus callosum having average

IQ suggest a diminished appreciation of the subtleties involved in

the appreciation of jokes during social interactions [30]. The brainbehavior

correlation for humor comprehension and appreciation

is affected after generalized brain injury or cerebellar degeneration

[31,32]. An altered sense of humor is noted in conditions like

dementia [33] relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis [34].

systemic sclerosis[35]. amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [36] .cognitive

impairments [37]. Parkinson’s [38] and cerebellar degeneration [32].

For example, suits et al (2012) showed that verbal, visual, motor, and

tactile humor appreciation and comprehension were significantly

lower among preschool children with epilepsy than in matched

healthy controls. In rare instances, there are reports of temporary or

permanent loss of sense of humor [39].

Topics:

This list of compiled publications covers a wide range of topics

related to humor in neurology, nervous disorders, and diseases. The

most frequently targeted disease conditions for studying humor are

dementia, pathological laughter, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and

stroke. The therapeutic or treatment potential of humor in nervous

diseases are minimally mentioned in few publications.(i) Dementia:

Research on patients with dementia has postulated whether their

humor styles (adaptive or maladaptive) are predictive of the strong

or weaker purpose they hold in their daily life [40,41]. recorded how

discourse comprehension rather than single-word comprehension

was impaired in Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia

as compared to healthy controls. Despite these deficits and the

recognition of an organic basis, positive humor is shown to have

a vital role as complementary and alternative medicine [42] in

ameliorating the quality of life by maintaining sustaining an enduring

relationship strength between people with dementia and their carers

throughout the disease [43-45]. Further, the use of medical clown

stand-up comedy and improvisation workshops on people with early

stages of dementia has shown therapeutic benefits as improvements

in memory, learning, sociability, communication, and self-esteem

in these patients [46,47]. Objective and empirical studies on this

population are still plagued by the absence of a standard or valid

behavioural observation system that covers aspects like humor style,

response, and contribution, which was attempted to be fixed in a

recent study [48].(ii) Pathological Laughter:

Some nervous disease and mental illness conditions like vascular

pseudobulbar palsy, motor neuron disease, Gilles de la Tourette

Syndrome, Angelman Syndrome, psychopathy, personality disorders,

schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder have earned a stereotype that

such persons laugh unexpectedly, disruptively, incorrectly, or

uncontrollably. Names like nervous-pathological laughter, emotional

lability, or dysregulation disorder are used to designate these

conditions. Other terms like dysprosopeia, or sham mirth have been

used to refer to pathological laughter [49,50]. There is also a version

of Gelastic epilepsy with seizures in which laughter is the major

symptom. Although ictal laughter appears mechanical and unnatural,

sometimes it can be mistaken as normal. The hypothalamus, frontal

and temporal poles have been implicated in this type of laughter

[51-58].Humorous cartoons on everyday life situations used as an

indicator of neuropsychological deficits failed to elicit the desired

levels of humor in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy [59].“Normal” laughter is typically caused by tickling, social cues, and

laughing gas. First described by German neurologists H. Oppenheim

and M. Jastrowitz, the term Witzelsucht(for joking addiction) refers

to a set of pure and rarely neurological symptoms characterized

by a tendency to make puns, tell inappropriate jokes, or relate

pointless stories in socially inappropriate situations. These patients

typically lack insight into their condition. An early observation noted

how pathological laughing and crying are a sign of occurrence or

recurrence of tumors in the brainstem [60,61]. Others have attributed

the symptoms to decreased blood flow in the right frontal lobe

tumors, poor concentration, extreme distractibility, and difficulty

with visuospatial tasks as seen on Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

[62,63].

Therapeutic Humor:

Therapeutic humor is used as an adjunct or form of complementary

medicine to relieve pain or stress and improve a person’s sense of

well-being involving the use of exercises, clowns, comedy movies,

books, games, or puzzles. Also called several variants like laughter

yoga therapy, hospice, or medical humor, the nomenclature varies

with the purpose, by whom, how, or type of settings where they are

used. At a very early time in history, forced laughter and crying along

with atropine or atropine-like drugs were found to be effective in

the control or modification of motor discharge seen in Parkinson’s

Disease [64].Humor based therapies have been tried on many nervous

disorders like organic and psychogenic epilepsy [65,66].mild cognitive

impairments [67] and Parkinson’s disease (Bega et al. 2017; DeCaro

& Brown, 2016) [68,69]. Humor-based therapies claim adjunct value

to the main course of organic medicine-based interventions to even

alter the functional processing of certain areas in the brain [70,71]. So

much so, a dose of non-offensive or non-derogatory humor (Wear et

al. 2006) [72]. is recommended to carers for routine home or nursing

management of neuropsychiatric patients (van der [73-75]. But, there

are doubts about whether humor in psychotherapy can be ever taught

[76].

Conclusion

There are both claims and counterarguments on the therapeutic benefits of humor. There is a lack of consensus on what is humor and

what are its components. The overall quality of evidence is anecdotal

and low with a substantial risk of bias in all studies. Non-humorous

laughter attains a higher effect size than humorous laughter. Humor

research in neurology needs to attain maturity. More careful “clinical

trial” research needs to be mounted to determine the conditions

under which humor works best if at all they work. There have been

different outcomes with different populations. The type of patient,

the kind of humor, the type and severity of illness, the psychosocial

contexts should be considered. Laughter-inducing therapies could

be cost-effective treatments are at best hold promise as low-cost

complementary or adjunct to main therapy. More methodologically

rigorous research is needed to provide evidence for this promise.

An often repeated line is: Laughter is the best medicine. Children

are recorded to laugh around 150-400 times per day. An average adult

laughs 15-20 times a day. Humor is the antidote to stress, pain, and

conflict. A 10-minutes of laughter and a few hours of pain-free sleep

per day do not cost anything. It is noted that 13 muscles are used in

smiling, while 47 muscles are strained in frowning. Laughter increases

oxygen flow, relaxes muscles, helps fight infection, and energizes and

increases breathing. It adds days to one’s lifespan. Laughter-induced

brain stimulation improves alertness, creativity, and memory. With

so many advantages, humor can stand as first line of treatment for

seniors or persons with neurological challenges.