Journal of Oral Biology

Download PDF

Case Report

Full Mouth Reconstruction in a Diabetes Mellitus Type I Patient – A Case Report with 5 Years Follow-Up

Braz de Oliveira R, Gaspar J, Reis N* and Fernández-Guallart I

Department of Periodontology and Implant Dentistry, New York

University, New York, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Reis N, Department of Periodontology and Implant Dentistry, New York University, C/O Dr Paul YC Yu, Clinic 5W, 345 E 24th St, NY 10010, New York, USA Tel: +1-347 279 29 58; E-mail: ycy233@nyu.edu

Submission: 28-10-2019

Accepted: 26-11-2019

Published: 30-11-2019

Copyright: © 2019 Oliveira RB, et al. This is an open access article

distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Periodontal disease is one of the most common oral diseases, caused

by a combination of poor oral hygiene and host defense response. It can be

infl uenced by genetic, environmental and/or developed conditions such as

smoking and diabetes mellitus. Periodontitis leads to bone resorption and

has a reported relationship with peri-implantitis development and implant

failure. However, when sugar levels are controlled, even diabetic patients

can have a long-term success and survival of dental implants. In addition,

the patient’s ability to maintain a good oral hygiene has been reported as

a critical factor to achieve that goal. Dental implants are a good option

for these patients, although there are some factors that should be ensured

prior to the treatment, such as improvement and maintenance of oral

hygiene levels, compliance in disease-control and quitting or reducing of

smoking. The purpose of this case report with 5 years follow-up is to review

the importance of motivation, education and maintenance in a patient

who received dental implants as a type I diabetic with a history of chronic

heavy smoking and poor oral hygiene.

Introduction

Periodontal disease is a chronic infl ammatory disease that aff ects

the periodontium. It is one of the most common oral diseases, caused

by a combination of poor oral hygiene and host defense response,

and can be infl uenced by genetic, environmental and/or developed

conditions such as smoking and diabetes mellitus. Periodontitis

leads to bone resorption, which, without proper maintenance, can

ultimately lead to a hopeless prognosis [1,2].

In cases of partial or complete edentulism, osseointegrated

implants as a support for dental prostheses are a viable treatment

option to replace the missing teeth which nowadays is becoming

more accepted due to its high success rate. However, mechanical and

biological risk factors can cause implant failure. Mechanical factors

pertain to implant characteristics such as body design and surface

architecture, while biological factors involve host aspects like chronic

heavy smoking (more than 10 cigarettes a day), diabetes mellitus, or

presence of periodontal disease. In literature, these biological factors

are considered as relative contraindications for dental implants [3-5].

Smoking can aff ect wound healing due to the decrease in blood

supply in periodontal tissues and therefore infl uences the bone

quality. However, it is reported in the literature that reducing the

number of cigarettes can decrease the complications with dental

implants [6].

Diabetes mellitus type I is characterized by high glucose levels

in the blood due to lack of insulin production, which hinders host

resistance. Th is consequently delays wound healing and increases

the risk of infection specially in the soft tissue. However, literature

reports that diabetic patients with controlled sugar levels can have a long-term success and survival of dental implants [7]. Likewise, the

patient’s ability to maintain a good oral hygiene has been reported as

a critical factor in achieving that goal.

Early loss of teeth due to periodontal disease can be associated

both with diabetes mellitus type I and chronic heavy smoking habits.

Young patients that started to lose their teeth due this condition are

worried about esthetics, and they are not compliant in using removable

dentures as they prefer fi xed prostheses. Dental implants are a good

option for these patients, although there are some factors that need

to be considered prior to the treatment, such as improvement and

maintenance of oral hygiene levels, compliance in disease-control

and quit/reduce smoking.

Th e purpose of this case report with 5 years follow-up is to

review the importance of motivation, education and maintenance in

a patient who received dental implants as a type I diabetic, with a

history of chronic heavy smoking and poor oral hygiene.

Materials and Methods

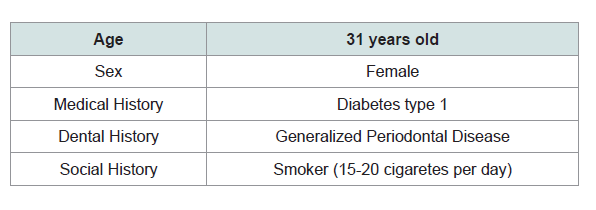

A 31 year old Caucasian female patient presented in the private clinic in 2011 with the chief complaint “I want to replace my teeth with some fi xed restoration, not removable”. Th e medical, social and dental history of the patient were reviewed: she had diabetes type I (HbA1c was 6.7%) and was taking insulin as medication to control the disease. Furthermore, she was a chronic heavy smoker (15-20 cigarettes per day) and reported that she already had some teeth extracted due to generalized periodontal disease (Table 1). At that time, she was using a removable partial denture, but she was not comfortable with it. Aft er comprehensive examination, the proposed treatment plan included extraction of all the remaining teeth and replacement with dental implants and a fi xed hybrid prosthesis in both arches. Th e patient understood the pros and cons of the treatment, agreed, and signed the consent form to proceed with the presented treatment plan.

Before starting with the surgical treatment, the patient was

advised that the diabetes mellitus should be well controlled, so when

she came for surgery her HbA1c levels were 6.1%. In November of

2012, the fi rst surgery was performed, consisting of extraction of the

remaining maxillary teeth followed by the delivery of an immediate

removable complete denture. For the mandible, the treatment

included extractions, immediate implant placement and immediate

provisionalization. One hour before the surgical procedure, the

patient took 2g of amoxicillin with clavulanic acid as prophylaxis.

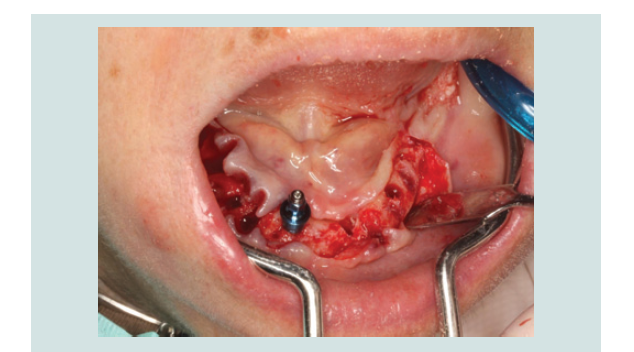

Th e procedure was carried out under local anesthesia (4% articaine with 1:100000 epinephrine, Inibsa, Portugal). Aft er anesthesia was

achieved, the teeth were atraumatically extracted using periotomes,

elevators and forceps. In the mandible, a midcrestal incision from

right fi rst molar to left fi rst molar areas was made and a full-thickness

fl ap was refl ected. Five implant sites were prepared following the

protocol established by the manufacturer, and immediate implants

were placed in the osteotomies (3 SIN 4.0 x 10 mm and 2 Biomet 3i

Osseotite 3.25/4 x 10 mm). Aft er that, temporary cylinders were placed

in four of the fi ve implants and a metal-reinforce acrylictemporary

was delivered and immediately loaded. Primary closure of the fl ap

was achieved with 4/0 silk sutures (Inibsa, Portugal). A maxillary

immediate removable complete denture was delivered, and a

mandibular immediate complete denture was screwed in. Th e patient

was prescribed antibiotic (amoxicillin 875mg with 125mg clavulanic acid every 12h for one week), analgesic (ibuprofen 600mg every 8h as

needed) and mouth rinse (0,12% chlorhexidine for 10 days). Aft er 1

week, she came back for a follow-up and the sutures were removed.

Th e healing process was uneventful, with no infection, infl ammation

or pain.

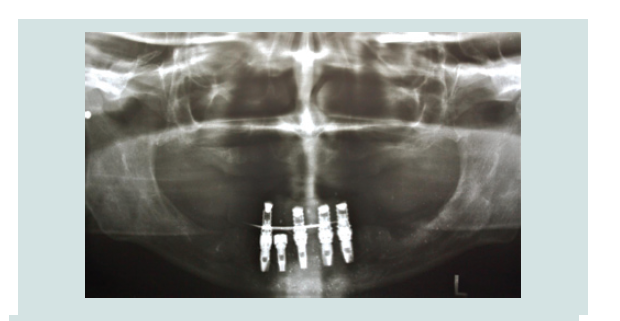

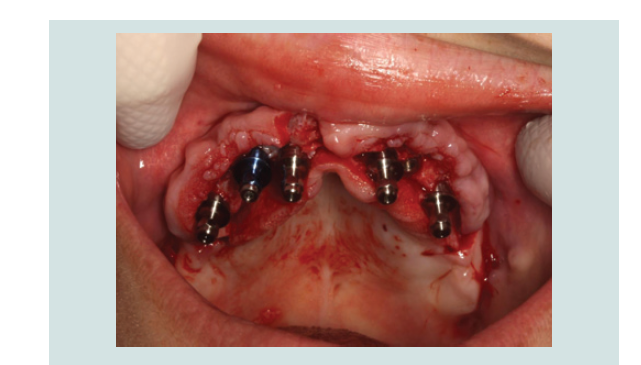

In March of 2013, a second surgery was performed in order to

place six implants in the maxilla. Th e same pre-operative and surgical

protocol was followed, and in this case a vertical incision was made

in the midline to facilitate the refl ection of the full-thickness fl ap. Six

implants were placed (2 SIN 4.0 x 10 mm implants and 4 EBi 4 x 4.1 x

8.5 mm implants) and submerged with cover screws. Primary closure

of the fl ap was achieved with 4/0 silk sutures (Inibsa, Portugal). Th e

patient continued to use the maxillary removable complete denture aft er relining it. Th e same post-operative protocol and instructions

were given to her, and in the follow-up visit the healing was again

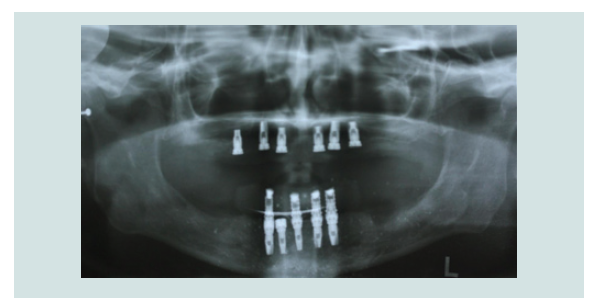

favorable (Figure 1-9).

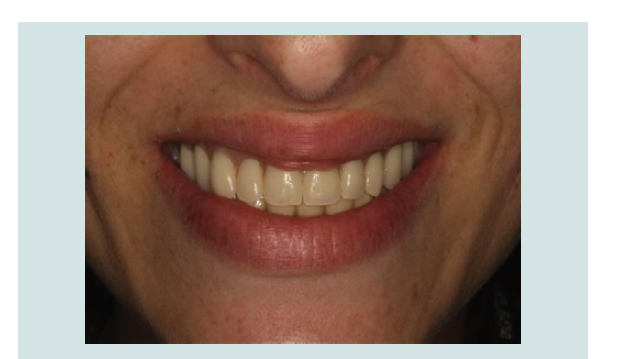

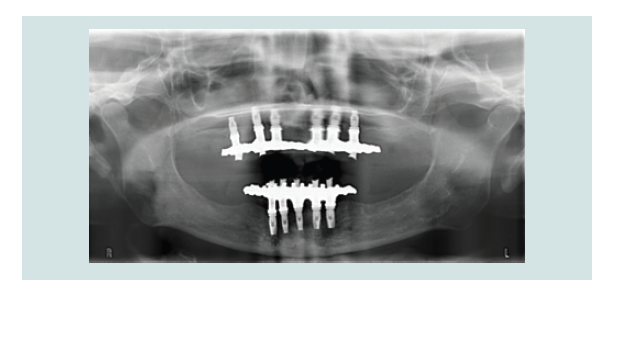

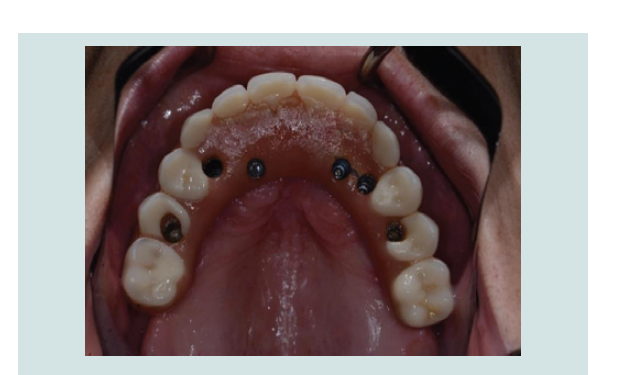

By the end of 2013, both maxillary and mandibular fi nal

restorations (fi xed hybrids) were delivered (Figure 10-13).

During the following 5 years, the patient came back to the

dental offi ce for maintenance visits every 6 months, where oral

hygiene instructions, education about diabetes mellitus control

with medication (patient HbA1c values were always under 8%) and

motivation to quit/reduce smoking were reinforced (Figure 14-19).

Discussion

According to literature, patients with history of periodontal

disease are more susceptible to periimplantitis [9]. In the systematic review of Ferreira et al. (2018), it was concluded that the history of

periodontitis is associated with the occurrence of periimplantitis.

Similarly, in the meta-analysis of Sgolastra et al. (2015) it was

determined that periodontal disease is a risk factor for implant loss

and periimplantitis, and that it is also related to higher levels of

implant bone loss [10,11].

Smoking tobacco is also associated with teeth loss because it

causes soft tissue infl ammation, decreases salivary fl ow, suppresses

immune response and persuades vasoconstriction, thus facilitating

bacterial growth and deterring regeneration of the periodontium

[12,13]. According to the literature, even the exposure to tobacco

smoke is associated with periodontal disease when compared with

non-exposition to it [14]. Moreover, smoking has an imperative

eff ect in the incidence and development of periodontal disease, since smokers have 80% more risk of periodontal disease than smokers

who quit and nonsmokers. However, smoking cessation has a positive

eff ect in decreasing the risk of periodontal disease (around 14%) and

improves the response to nonsurgical periodontal therapy in the fi rst

year aft er quitting. Likewise, the risk of developing a periodontal

disease in quitters seems to be similar to the one for nonsmokers

[13,15]. In the systematic review of Dreyer et al. (2018), it was

reported that smoking tobacco is also a risk factor for developing

peri-implantitis [9]. However, this habit should not be considered as

an absolute contraindication for implant placement: even if there is a higher risk of failure during the initial healing time aft er surgery,

some authors like Chrcanovic et al. (2015) reported that this depends

on the implant surface’s roughness [16-19]. Th e patient in the current

case report reduced the number of cigarettes smoked per day before

performing the treatment, which could be considered as the fi rst key

factors for the long-term success of it [20] (Figure 14-19).

In the systematic review of Mauri-Obradors et al. (2017), it

was concluded that there is a correlation between diabetes mellitus

and periodontal disease [21]. Th e increase of glucose in the blood

is associated with higher risk of periodontitis due to alterations in

host-immune response against the biofi lm such as the decrease of

neutrophil adherence, chemotaxis and phagocytosis, all facilitating

bacteria to persist in the oral cavity [22]. Similarly, periodontal disease

may cause alterations in the glycemic control (measured using HbA1c)

in diabetic patients as reported in the systematic reviews of Simpson

et al. (2015) and Hasuike et al. (2017), where they found that diabetic

patients with periodontitis who undergo periodontal treatment

improved their glycemic control [23,24]. In the systematic review of

Guobis (2016) it was also stated that diabetes mellitus is an impending

factor for postoperative healing progression aft er implant placement.

As a consequence, this treatment option in diabetic patients should

be only performed in selected cases in which the patient is compliant

in controlling the disease as well as in coming to the dental offi ce

for follow-up appointments [25,26]. According to the literature, the

overall implant failure rate is not higher in diabetic patients when

compared with non-diabetic patients. However, those have a higher

risk of implant failure especially during osseointegration and in the

fi rst year aft er loading [27,28], and they also experience more implant

marginal bone loss in the long term [27]. In the systematic review

of Naujokat et al. (2016) it was concluded that the implant survival

rate aft er 6 years is similar for diabetic and non-diabetic patients.

However, aft er 20 years there is a decrease in the implant survival

rate in diabetic patients well controlled diabetic patients show better

results both in implant survival rate and osseointegration than noncontrolled

ones. Likewise, in the systematic review of Schimmel et al. (2018) it was found that levels of HbA1c greater than 8% are related to less implant survival rate when compared to lower levels [29,30]. Despite all of the above, in the case report of Balshi et al. (2007), it was demonstrated that although implants in diabetic patient have a diff erence in bone remodeling according to RFA and stability measurements, immediate loading protocol is successful and osseointegration survival rate is high [31]. In the systematic review of Naujokat (2016) it was concluded that there is low risk of developing

peri-implantitis in the fi rst years, however peri-implant infl ammation

increases in long-term follow-up in diabetic patients. In the

systematic review of Monje et al. (2017) it was concluded that the risk

is higher in patients with hyperglycemia compared to patient with

normal glucose levels in the blood and that smoking is not needed

to enhance hyperglycemia infl uence in the peri-implantitis [29,32]. Th e current patient’s HbA1c was being well controlled (always under

8%) by medication and this could be considered as the second key

factor for the long-term success of the dental implant in addition to

the patient’s smoking reduction (Figure 14-19).

One of the critical factors to stop the progression of the

periodontal disease is the plaque control performed by the patients.

Th e systematic review of Newton et al. (2015) concluded that the

dentist’s intervention explaining to the patient the severity of the

condition and the benefi ts of changing the oral hygiene care improves

the general oral health [33]. Aft er implant placement, the patient

should be encouraged to improve home oral care and to be present

in the recall visits every 3-6 months for professional oral care and

follow-up evaluation. If this is the case, the long-term prognosis of

the implants will improve [8]. In the study of Costa et al. (2012), it

was concluded that patients without preventive maintenance aft er

implant placement are more prone to peri-implant disease [34]. Th e

current patient was instructed and motivated to start and maintain

good oral homecare and to attend maintenance visits every 6 months,

which could be considered as the last key factor for the long-term

success of the dental implant treatment (Figure 14-19).

Conclusion

• Diabetes mellitus, heavy smoking and poor oral hygiene are

factors that can lead to periodontal and peri-implant diseases, and

consequently to teeth loss and/or implant failure.

• Clinicians should address those factors before considering

implant placement by educating the patient on diabetes mellitus

control, quitting/reducing tobacco and oral hygiene instructions.

• Implant placement with/without immediate loading is a valid

solution for well-controlled diabetic patients in need for fi xed

restorations.

• With proper maintenance, the implants placed on diabetic

patients can have high success rate with minimal bone loss over a

5-year period of time.

References

1. Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN (2017) Periodontal diseases.

Nat Rev Dis Primers 3: 17038.