Journal of Orthopedics & Rheumatology

Download PDF

Research Article

Pseudotumor Treated with Two-Stage Revision Due to Aggressive Osteolysis and Soft-Tissue Mass Following Metal on Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty

Yakkanti RR*, Nguyen D and Pretell-Mazzini J

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Miami, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Yakkanti RR, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, 1611 NW 12th Ave #303, Miami, FL 33136, USA, Tel:

502-689-3127; E-mail: ramakanth.yakkanti@jhsmiami.org

Submission: 11 September 2020;

Accepted: 02 November 2020;

Published: 16 November 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Yakkanti RR, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Introduction: This is a unique case of the largest reported pseudotumor in literature, treated with a custom acetabular component in conjunction with a total femur replacement.

Case: Patient is a 71-year-old male, with a large pseudotumor secondary to Metal on Metal total hip arthroplasty, who had chronic pain for 8 years prior to presentation. Imaging revealed extensive soft tissue mass and osteolysis. Patient underwent two-stage surgery, with 1st stage involving surgical debridement of pseudotumor and fixation of custom triflange acetabular component, 2nd stage involved a total

femur replacement.

Conclusion: This case demonstrates the evaluation and management of a large pseudotumor. A two-stage revision in complex pseudotumor cases, with complete revision of the implants and excision of the pseudotumor, to achieve clinical improvement and decrease complications is a viable option.

Keywords

Pseudotumor; Total hip arthroplasty (THA); Metal on metal (MoM); Revision surgery; Mega prosthesis; custom implants

Introduction

There are multiple bearing surfaces available for Total Hip

Arthroplasty (THA), with Metal On Metal (MoM) implants being

a common choice [1]. MoM implants were developed for better

volumetric wear propertiesand improved stability [2]. However,

MoM implants have high rates of metallosis and pseudotumor

formation,1–39%of cases [1,2].

Pseudotumors are defined as non-neoplastic, non-infectious

cystic or solid mass forming lesions1. In many cases they develop due

to biological reactions similar to hypersensitivity type 4 reactions to

metal ions, released from abrasive wear of the prosthesis, leading to

osteolysis and soft-tissue damage [3]. Clinical presentation may vary

from absence of symptoms to pain associated with rashes, instability,

nerve palsy and prosthetic loosening with osteolysis [4].

Classification systems for stratification, diagnosis and management

pathways for implant failure and soft tissue complications due to

pseudotumors have been described in literature; however, no current

evidence-based surgical management guideline exists [5,6].

We describe a patient with a failed MoMTHA due to a large

fibroblastic pseudotumor causing osteolysis of the left hemipelvis

and femur. To our knowledge, this is the first case report in which a

custom tripflange acetabular implant in conjunction with total femur

mega prosthesis was used during a two-stage revision for treatment

of a pseudotumor.

The patient was informed that data concerning the case would be

submitted for publication, and he consented.

Case Report

A 71-year-old male with BMI of 27.7 and history of a left

MoMTHA in 1999 presented to our institution with 8 years of

chronic, progressive left groinand thigh pain which was worse

with weight-bearing and at night. He had complete loss of hip

and knee range of motion and required a walker for ambulation.

Surgical history includes left acetabular liner and femoral head

exchange, without relief of symptoms, 3 years prior to presentation.

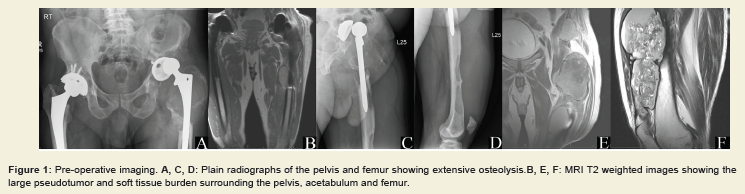

Radiographs showed extensive osteolysis surrounding the acetabular

implant with posterolateral subluxation of the femoral head, as well

as severe osteolysis involving the femoral shaft with multiple large lytic lesionsextending to the distal femur (Figure 1A-D). The MRI

demonstrated a heterogeneous mass with layering of contents, a

low signal intensity mass invasion into the ilium, large soft tissue

mass on the anterior aspect of the thigh with cortical erosion and

breakthrough into several points along the anterior cortex of the distal

femur (Figure 1B,C,F). Laboratory results including CBC, BMP, ESR,

CRP, Serum chromium and cobalt levels were within normal limits.

The osteolytic nature of the soft tissue mass prompted biopsy, which

ruled out neoplastic or infectious process.

Figure 1: Pre-operative imaging. A, C, D: Plain radiographs of the pelvis and femur showing extensive osteolysis.B, E, F: MRI T2 weighted images showing the

large pseudotumor and soft tissue burden surrounding the pelvis, acetabulum and femur.

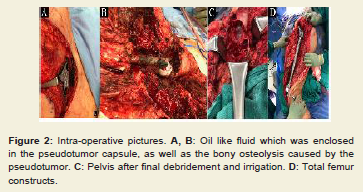

Figure 2: Intra-operative pictures. A, B: Oil like fluid which was enclosed

in the pseudotumor capsule, as well as the bony osteolysis caused by the

pseudotumor. C: Pelvis after final debridement and irrigation. D: Total femur

constructs.

Due to the complexity of the necessary reconstruction the

surgery was staged. First stage involved complete debridement of

the pseudotumor surrounding the left hip, pelvis and proximal thigh

using a Kocher-Langenbeck approach with proximal extension

to iliac crest, and distal extension to lateral approach to femur.

Dissection of the fascia lata revealed a viscous, black, oil-like fluid

(Figure 2A), contained in the pseudotumor capsule. Large portions

of the hip abductors and quadriceps muscles were non-viable due to

metallosis. There was a “pseudo-membrane” covering the proximal

thigh, with severe osteolysis of the proximal femur, acetabulum and

iliac bone (Figure 2B). The pseudo-membrane was debrided, and the

operative field was copiously irrigated (Figure 2C). Reconstruction of

the acetabulum with a custom patient-matched triflange acetabular

component was performed. (Zimmer/Biomet; Warsaw, IN.)

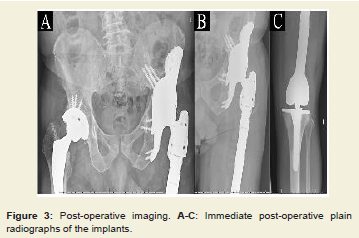

Three days later the second stage involving, resection of the distal

two thirds of the femur due to severe bone loss, and subsequent

reconstruction with a total femoral replacement(Zimmer/Biomet;

Warsaw, IN) using a constrained liner in the hip and a standard

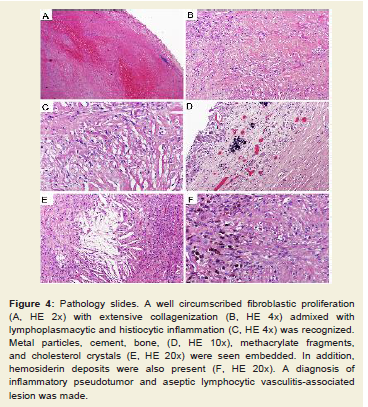

rotating-hinge for the knee, was performed (Figure 2D and 3A-C). Final pathology was compatible with a septic lymphocytic vasculitisassociated

lesion (ALVAL)and inflammatory pseudotumor (Figure 4).

Post-operatively, the patient was allowed full weight bearing with a hip abduction brace that was discontinued at 6 weeks. At his recent follow up (14 months post-op) the patient had a Harris hip score of

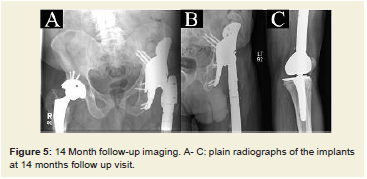

82, which is compatible with a successful outcome. There was no radiographic evidence of osteolysis or component loosening (Figure 5A-C). Blood chromium and cobalt ions were within normal limits.

Discussion

Pseudotumors are mass forming lesions occasionally associated

with MoM THA, and are described as non-infectious, non-neoplastic

soft-tissue proliferations, they can display variable morphology,

including solid, cystic or mixed lesions. These lesions are due to

immune mediate reactions that trigger a cytokine cascade similar

to type-4 hypersensitivity reactions to metal ions more accurately

described as ALVALs.2Local toxicity of the metal ions causes

subsequent osteolysis and soft-tissue cell and fiber damage increasing

the inflammatory stimuli.Schmalzried and Callaghan reported that

these aggressive inflammatory stimuli could lead to lysis occurring at

any point along the space of the hip joint [7].

In patients with pseudotumors, clinical symptoms do not

necessarily correlate with the size of a pseudotumor found on MRI

or ultrasound imaging [7-9]. Elevated serum cobalt might have an

association with tumor size, but not necessarily to symptoms, as 57-

78 % of pseudotumor cases are asymptomatic [1,2,5].

Pseudotumors with Cobalt (Co) and Chromium (Cr) levels

of >7 ppbare concerning and >20μg/L, with or without symptoms,

receive serious consideration for revision arthroplasty [2,3]. Metal (chromium and cobalt) ions and particles released from implants

may lead to devastating cardiac and neurological effects, osteolysis,

as well as soft tissue damage [10]. Risk factors for the formation of

a pseudotumor are cobalt levels>5μg/l, female gender, pain, and

a high acetabular inclination angle >55° [8]. In our case a massive

pseudotumor process with extensive involvement of bone stockin

the pelvis and femur developed. This is despite normal levels of metal

ionsmeasured andappropriate positioning of implants confirmed on

imaging.

Figure 4: Pathology slides. A well circumscribed fibroblastic proliferation

(A, HE 2x) with extensive collagenization (B, HE 4x) admixed with

lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic inflammation (C, HE 4x) was recognized.

Metal particles, cement, bone, (D, HE 10x), methacrylate fragments,

and cholesterol crystals (E, HE 20x) were seen embedded. In addition,

hemosiderin deposits were also present (F, HE 20x). A diagnosis of

inflammatory pseudotumor and aseptic lymphocytic vasculitis-associated

lesion was made.

Figure 5: 14 Month follow-up imaging. A- C: plain radiographs of the implants at 14 months follow up visit.

Treatment options include isolated revision of the femoral or

acetabular component, or complete-revision surgery [10]. In many

cases treatment can be performed with the same principles used in

revisions for aseptic loosening. Cementless cups and femoral implants

can often be used in combination with cancellous bone grafting if

the bony defects are not significant. Usually the choice for revision

techniques and implants is dependent on the extent of bony erosion.

However, literature to guide surgical planning of pseudotumors is

limited, especially with large lesions involving extensive bone and

soft tissue damage. Established guidelines for non-pseudotumor

revision THA do not provide adequate guidance. The treatment of

this condition is associated with high reintervention rates requiring

a second revision in almost 35% of the cases. Major complications

occur in up to 50% of cases, with patients often experiencing the same

level of pain and functional limitations as prior to the revision surgery

[3].

Another important consideration is the choice of implant

surfaces used in revision surgery. It is generally advisable to avoid

using a metal on metal coupling when performing a revision for

pseudotumor, options of ceramic on polyethylene are preferred, as

they pose the lowest risk of producing metal ion debris.

This case report details a pseudotumor where the soft tissue

component, and the associated osteolysis wereextensive, making

this one of the largest pseudotumors reported in literature. Due to

the size of the pseudotumor a unique staged surgical plan had to be

implemented. Although traditionally revisions are performed in a

single stage, evaluating the imaging pre-operatively gave the authors

insight into the extent of osteolysis, as well as soft tissue reaction

which caused a large pseudotumor to form. There was concern preoperatively

that the amount of dissection required to thoroughly

debride the pseudotumor would be extensive. Especially at the distal

aspect of the thigh where the capsule was abutting the neurovascular

bundle.

Staging was thought to decrease surgical complications, mainly

infection due to reduction of surgical time in one anesthesia episode [4,10]. Custom implants were indicated in order to address the

irregular and extensive areas of bone loss. Due to the damaged

abductor muscles, a constrained liner was used to decrease the risk

of dislocation. Aggressive release of the fibrosis at the knee joint was

also performed at the time of the standard total femur replacement

procedure, providing improved knee range of motion. The utilization

of both a total femur replacement as well as a custom triflange

acetabular implant was unique in this setting and required extensive

planning and coordination of care. Due to the potentially extensive

nature of the dissection for both the acetabular component fixation

as well as the total femur replacement and the inherent difficulty in

performing these procedures in deficient bone, a more conservative

approach with staging the procedure in order to reduce potential

complications was thought to be appropriate.

With this case report, the authors emphasize the importance of

approaching an extensive pseudotumor with careful planning and

attention to detail. Complete characterization of the lesion preoperatively

is especially important in order to guide appropriate

surgical approach, and implant choices, including custom implants

when necessary.

Case reports such as these are vital in providing practicing

surgeons and researchers with an important fund of knowledge

in unique cases, where large volume research studies are difficult

to perform. Case series and case reports make up the majority of

the available literature in regard to revision surgery secondary to

pseudotumor in total hip arthroplasty, specifically in cases involving

extensive bone loss and large volume formation of pseudotumor.

As there are no well documented guidelines to treatment in these

scenarios, this case report and others can serve as an example for a

successful treatment option.

Conclusion

We recommend a two-stage revision in large complex pseudotumor cases with complete revision of the implants as well as excision of the pseudotumor to achieve clinical improvement and decrease complications. To our knowledge, this is the first case report in which a custom triphalangeal acetabular implant in conjunction with a total femur reconstruction was done with a two-stage revision for treatment of a pseudotumor due to MoM THA.