Journal of Parkinsons disease and Alzheimers disease

Download PDF

Research Article

Autophagy Monitoring in Cerebral Pericytes from Alzheimer’s disease Mouse Model in an Inflammatory Environment

Julie V, Vincent T, Hanitriniaina R†, Benjamin F, Thierry F and Guylène P*

University of Poitiers, Neurovascular Unit and Cognitive Disorders,

PôleBiologieSanté, Poitiers, France

†Present address: University of Poitiers, EA4331, Laboratoire

Inflammation, Tissus Epithéliaux et Cytokines, Pôle Biologie Santé,

Poitiers, France

*Address for Correspondence: Guylène P, University of Poitiers, Neurovascular Unit and Cognitive

Disorders, PôleBiologieSanté, Poitiers, France; E-mail: guylene.page@

univ-poitiers.fr

Submission: 01 August, 2022

Accepted: 27 September, 2022

Published: 03 October, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Ben-Julie V, et al. This is an open access article

distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background: The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a complex neurovascular

unit involving pericytes as multi-functional cells that play a crucial role in

maintaining homeostasis. In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), platelet-derived

growth factor receptor-β (PDGFRβ) immunostaining revealed significantly

reduced pericyte coverage of brain capillaries as well as reduced pericyte

numbers in AD cortex and hippocampus compared with control brains.

However, the mechanisms of pericyte loss have yet to be completely defined.

Moreover, we have previously shown that, in microglia, interleukin-1β (IL-

1β)-induced inflammation blocks autophagic flow, a physiological process

involved in the degradation of proteins including the β-amyloid peptide. Thus,

we evaluated whether the inflammatory response in AD impaired autophagy

in pericytes.

Methods: A longitudinal autophagic status monitoring was performed

in pericytes purified from brains of AD and wild type (WT) mice at 3, 6 and

12 months. Furthermore, the impact of an inflammatory environment was

studied not only in these primary pericytes but also in a pericyte cell line

developed in the laboratory.

Results: Primary pericytes from AD mice displayed a significant increase

of autophagic markers at 3 months and that in later stages their expressions

were like those of WT mice. In addition, IL-1β-induced inflammation did not

modify the expression of autophagic markers or those of mTOR signaling

pathway in both primary and immortalized mouse pericytes.

Conclusions: For the first time, these data highlighted that autophagy

is activated in primary pericytes from AD transgenic mice at 3 months.

In addition, inflammation has no impact on autophagic flow under our

experimental conditions.

Keywords

Pericytes; Alzheimer’s disease; Inflammation, Autophagy,

Interleukin-1β

Introduction

We have previously published the first results on the interaction

between autophagy and inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease (AD)

[1-3]. We showed that the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-

1β (IL-1β) was responsible for blocking autophagy and that microglia

was the most sensitive cell type in primary neuron/astrocyte/

microglia tri-cultures [1]. These last results are consistent with recent

data concerning the failure of these brain resident immune cells

during AD [4]. However, other cells showed senescence and died in

AD such as pericytes [5]. Recently, authors showed elevated soluble

platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β (sPDGFRβ) levels in

cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), indicating pericyte injury and blood brain

barrier (BBB) breakdown [6,7]. So, sPDGFRβ could be a promising

early biomarker of human cognitive dysfunction [7,8]. Pericytes are

mural cells abundant in the microvasculature in the central nervous

system and physically the closest cells to brain endothelial cells (EC)

wrapping around them, joined by gap junctions, and interfacing

bypeg-and-socket structures [9,10]. Their functions are largely explored from embryonic to adult periods of development [6,11-13].

Under physiological conditions, pericytes regulate BBB integrity,

angiogenesis, phagocytosis, cerebral blood flow (CBF) and capillary

diameter, neuro inflammation and multi potent stem cell activity [9-14].The presence of pericytes is essential because knock-out mouse

models by deletion and/or genetic manipulation of PDGFRβ and/

or PDGFB genes result in blood vessel dilation, EC hyperplasia, and

micro aneurysm formation [15]. Furthermore, in double transgenic

APPsw/0/PDGFRβ+/- mice, the loss of pericytes early increased brain

β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) levels, accelerated amyloid angiopathy and

cerebral β-amyloidosis, led to the development of tau pathology and

an early neuronal loss that is normally absent in APP transgenic mice

[16,17]. Many studies showed that pericyte dysfunction is associated

with AD neuropathology [18]. In fact, pericyte degeneration led to

BBB disruption and unrestricted entry and accumulation of bloodderived

products in brain (erythrocyte-derived hemoglobin and

plasma-derived proteins such as albumin, plasmin, thrombin, fibrin,

immunoglobulins and others) [19]. In humans with cognitive decline,

A β constricted brain capillaries at pericyte locations and generated

reactive oxidative species (ROS) which led to release of endothelin-1

acting via endothelin receptors (ETA) on pericytes and increasing

the constricting effects [20]. Neuro imaging studies in individuals

with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early AD revealed BBB

breakdown in the hippocampus before brain atrophy and dementia

[21-23]. The mechanisms of pericyte loss have yet to be completely

defined. AD is also characterized by a great inflammatory response and

by a blockage of autophagy [24-29]. In AD, both neuro inflammation

and systemic inflammation can disrupt the BBB by modifying the

tight junctions, damaging the vascular endothelial cell, degrading

glycocalyx, allowing peripheral hematopoietic cells to infiltrate neural

tissue and become part of the parenchymal microglia/macrophage

[23,24,30]. Notably, IL-1β contributes to BBB dysfunction [25,31].

Pericytes express several mediators (chemokines, cytokines) that

can enhance leukocyte extravasation and contribute to a cerebral

inflammatory phenotype [32,33]. At the same time, pericytes over express adhesion molecules that guide and instruct innate immune

cells after transendothelial migration [32]. Moreover, pericytes are

implicated in shaping adaptive immunity, with several studies that

point to an immunosuppressive role [34]. However, in AD, pericyte

loss also correlates with inflammation-mediated disruption of BBB

[32]. It is well known that inflammatory response in particular IL-

1β production impairs autophagy resulting in neuro degeneration

and memory loss in AD [1-3,35]. However, the autophagic status of

pericytes in AD is still poorly understood. Therefore, this study aims

to explore the autophagic status of pericytes from AD mice versus

wild type (WT) mice at 3, 6 and 12 months. The analysis focused on

the expression of Beclin-1, a protein involved in autophagic initiation

[36], p62 as a cargo protein of the material to be eliminated [37],

and soluble LC3 I and membranaryunsoluble LC3 II isoforms as

elongation and fusion signals with lysosomes [38]. Furthermore, a

pericyte cell line developed in the laboratory was also used to study

the impact of IL-1β in autophagy and mTOR signaling pathway.

Materils & Methods

Chemical products:

Sodium fluoride (NaF), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF),

protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails, dithiothreitol (DTT),

mouse monoclonal Anti-β-Actin antibody, mouse anti-alpha smooth

muscle actin antibody (αSMA), and all reagent-grade chemicals for

buffers were purchased from Sigma (St Quentin Fallavier, France),

sodium pentobarbital from CEVA, Animal Health (Libourne,

France), 4X Laemmli sample buffer, 4-15% mini-PROTEAN® TGX™

gels, Tris-glycine running buffer and Trans-Blot® Turbo™ Transfer

System from Biorad (Marnes-la-Coquette, France),Quant-it® protein

assay. For western blot, primary antibodies against Beclin-1, mTOR,

p70S6K (total and phosphorylated forms), mouse anti-GFAP for

immunocytofluorescence, secondary anti-rabbit or anti-mouse

IgG antibody conjugated with Horseradish Peroxydase (HRP) and

mouse recombinant Interleukin-1β (IL-1β)were purchased from Cell

Signalling (Ozyme, St Quentin Yvelines, France) except p62/SQSTM1

and LC3I/II from MBL (CliniSciences distributor, Nanterre, France),

rabbit polyclonal anti-NG2 Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycan (NG2)

and anti-platelet derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFRβ)

antibodies from Proteintech France, a rabbit polyclonal antibody

anti-von Willebrand Factor (vWF) from Merck Millipore (Molsheim,

Alsace France), macrosialin or murine homologue of the human

CD68 and secondary antibodies goat anti-rat R-Phycoerythrin (RPE)

from AbDSerotec(Düsseldorf, Germany), IgG- and protease-Free

Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) and secondary anti-mouse-Alexa 488

or anti-rabbit-TRITC from Jackson Immuno Research Europe Ltd

(Interchim distributor, Montluçon, France).Cell culture:

For this work, mouse pericytes were extracted following

experimental protocol described in our patents (FR17/57643 and

US-2022-0010258-A1). Two cultures of mouse pericytes were used:

a mouse primary culture of pericytes and a mouse cell line of

pericytes developed in the laboratoryas indicated in the patent.Pericytes came from brains of APPswePS1dE9 or wild type

(WT) mice at 3, 6 and 12 months of age. These transgenic mice were

purchased from Mutant Mouse Resources and Research Centers (Stock No: 34829-JAX, USA) displaying Alzheimer phenotype

(Authorization from “Haut Comité de Biotechnologiefrançais”

(HCB) to Pr Guylène Page, number 2040 for reproduction, treatment,

behavioral tests and ex-vivo experiments). Wild type (WT) with

B6C3F1 background and APPswePS1dE9 mice were obtained by

crossing a male APPswePS1dE9 mouse with a WT female mouse (from

Charles River, strain Code 031) as explained previously [39].The use

of animals was approved by the Ethical and Animal Care Committee

(N˚84 COMETHEA, Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation

Poitou-Charentes, France). At weaning, all mice were genotyped by

polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of tail biopsies according

to the manufacturer’s recommended protocols. All animal care and

experimental procedures conformed with the French Decree number

2013–118, 1 February 2013 NOR: AGRG1231951D in accordance

with European Community guidelines (directive 2010/63/UE). All

efforts were made to minimize animal suffering, as well as the number

of animals used. The animals were housed in a conventional state

under adequate temperature (23 ± 3˚C) and relative humidity (55 ±

5%) control with a 12/12 h reversed light/dark cycle with access to

food and water ad libitum.

As a method of immortalization, we used the transformation

with oncoprotein of murine polyomavirus, Polyoma middle T

antigen. Protocol was already described for murine endothelial cells

[40]. Stable cerebral pericyte cell line has been obtained 2 months

later. This pure cell line displayed features of pericytes with αSMA,

NG2, PDGFRβ and no vWF, ZO-1, GFAP nor CD68 (markers of

endothelial cells, astrocytes and microglia, respectively) expressions

as shown in additional file 1 (see Supplementary Information).

Cell treatment:

Primary pericytes and immortalized pericyteswere seeded in

24-well plates (150,000 and 50,000 cells/well, respectively) to study

their autophagic status in control or inflammatory conditions.

Inflammation was induced by IL-1β at 400 pg/mL during 48 hours

in a cell incubator. After 48hr-treatment, cells were lysed in ice-cold

lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM NaCl pH 6.8, 1% (v/v) Triton

X-100, 1 mM PMSF, 50 mM NaF, 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor and 1%

(v/v) phosphatase inhibitor cocktails). Lysates were sonicated for 10

sec and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatants

were collected and analyzed for protein determination using a Quantit

® protein assay kit. Samples were frozen at -80°C until western blot

experiments.Western blot:

Samples (40 μg proteins) were prepared for electrophoresis by

adding 4X Laemmli sample buffer containing 0.05 M DTT and loaded

into 4-15% mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ gels with Tris-glycine SDS

running buffer. Systems ran at 200 V for 35 minutes. Then, gels were

transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using Trans-Blot® Turbo™

Transfer System (25V, 3 min for 0.2 μm nitrocellulose MINI gel).

Membranes were washed for 10 min in Tris-buffered saline/Tween

(TBST: 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, 0.05% Tween 20)

and aspecific antigenic sites were blocked 2h in TBST containing 10%

BSA for detection of LC3 and in TBST containing 5% non-fat milk for

other proteins. Antibodies used were rabbit anti-Beclin-1, anti-p62,

anti-LC3, anti-total mTOR, anti-total p70S6K, anti-PS2448-mTOR, anti-PT389-p70S6K all at a dilution 1:500 in TBST containing 5% BSA

overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed twice with TBST and then

incubated with the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody anti-rabbit

IgG (1:1000), during 1 hour at RT. Membranes were washed again

and exposed to the chemiluminescence Luminata Forte Western HRP

Substrate (Millipore, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France) followed by

signal’s capture with the Gbox system (GeneSnap software, Syngene,

Ozyme distributor). After 2 washes in TBST, membranes were probed

with mouse antibody against β-actin (1:1000) overnight at 4°C.

They were then washed with TBST, incubated with HRP-conjugated

secondary antibody anti-mouse (1:1000 in blocking buffer) for 1h,

exposed to the chemiluminescence Luminata Classico Western HRP

Substrate (Millipore, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France) and signals

were captured. Automatic image analysis software is supplied with

Gene Tools (Syngene, Ozyme distributor). Protein/β-actinratios were

calculated and showed in the corresponding figures.CYTO-ID® Autophagy Detection Kit:

This live cell analysis kit provides a convenient approach for the

analysis of the regulation of autophagic activity at the cellular level.

Cell treatment was performed in 96-well plates (1,25,000 cells/well).

According to the supplier’s recommendations, cell medium was

gently removed after treatment and cells were washed with 200 μL

of 1X assay buffer containing 5% NBCS. Then, 100μL of 1X Assay

Buffer/5% NBCS containing 2μL/mL of CYTO-ID® green detection

reagent and 2μL/mL Hoechst 33342 nuclear stain were added in

each well. Plates were incubated 30 min at room temperature in a

black chamber. Then, cells were washed twice with 100 μL of 1X

assay buffer/5% NBCS and 100 μL of this buffer were added for

measurement of fluorescent signals (λExcitation: 480nm/λEmission:

530nm for CYTO-ID® green detection reagent and λExcitation:

340nm/λEmission: 480nm for Hoechst 33342 nuclear stain) by

using a ThermoVarioskan Flash spectral scanning multimode reader

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Illkirch, France).Rapamycin (1μM)as

an inducer of autophagy and Chloroquine (10 μM) as a lysosomal

inhibitor were included as positive controls. Ratios of fluorescent

intensity for CYTO-ID® green detection reagent /fluorescent intensity

for Hoechst 33342 nuclear stain were calculated and results were

normalized to control.LYSO-ID® Red Cytotoxicity Kit:

This GFP certified® live cell kit provides a rapid and quantitative

approach for determining drug- or toxic agent-induced lysosome and

lysosome-like organelle perturbations, for detecting phospholipidosis

and also the accumulation of autophagosomes by blocking the

downstream lysosomal pathway and/or intracellular trafficking

of autophagosomes also lead to increase in the accumulation of

intracellular LYSO-ID® red dye signal. A lysosome-perturbation agent,

verapamil (10 μM), is provided as a positive control for monitoring

changes in vacuole number and volume. A blue nuclear counter stain

is integrated into the detection reagentto identify cell death or loss. As

indicated for CYTO-ID®, cells were seeded in 96-well plates (1,25,000

cells/well) and treated with vehicle or IL-1β. After treatment, medium

was carefully aspirated and 100μl of 1X Assay Buffer containing 2%

of NBCS were added in each well. Then, the buffer was aspirated and

100μl of the 1X dual color detection reagent containing 1mL Dual

Color Detection Reagent, 8.8 mL Detection Buffer and 2% of NBCS for 10 mL of solution was added in each well. Plates were incubated

for 1 hour at room temperature and protected from light. At the end

of incubation, plates were gently washed twice with 100 μL of 1X

Assay Buffer/2% of NBCS and 80 μL of 1X Assay Buffer/2% of NBCS

were added before measurement of intensity of fluorescence. The red

lysosome stain can be read witha λExcitation: 540nm/λEmission:680

nm and the blue nuclear counterstain can be read with a λExcitation:

340nm/λEmission: 480nm. Ratios of fluorescent intensity for

LYSO-ID® red dye signal /fluorescent intensity for the blue nuclear

counterstain were calculated and results were normalized to control.Statistical analysis:

For biochemical analysis, results are expressed as means ±

SEM. To compare quantitative variables between primary pericytes

prepared from WT and APPswePS1dE9 mice treated or not with IL-

1β and between immortalized pericytes treated or not with IL-1β,

Mann-Withney’s tests were used. Longitudinal changes in parameters

occurring during the life were analysed with a Kruskal-Wallis test

followed by a post-hoc with Dunns test (GraphPad Instat, GraphPad

Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The level of significance was p < 0.05.Results

Monitoring of autophagy in primary mouse pericytes:

To determine whether autophagy changes occurred in pericytes

prepared from brains of APPswePS1dE9 mice at 3, 6 and 12 months

of age, immunoblottings of Beclin-1, p62, LC3 I and LC3 II were

performed. The levels of expression of Beclin-1 which is a key

component in the initiation of autophagosome formation significantly

increased by 31-fold in pericytes of 3-months old APPswePS1dE9

mice compared to age-matched WT mice [41]. On the contrary, a

robust decrease by 36- and 10.8-fold in pericytes of APPswePS1dE9

mice was observed at 6 and 12 months, respectively compared to

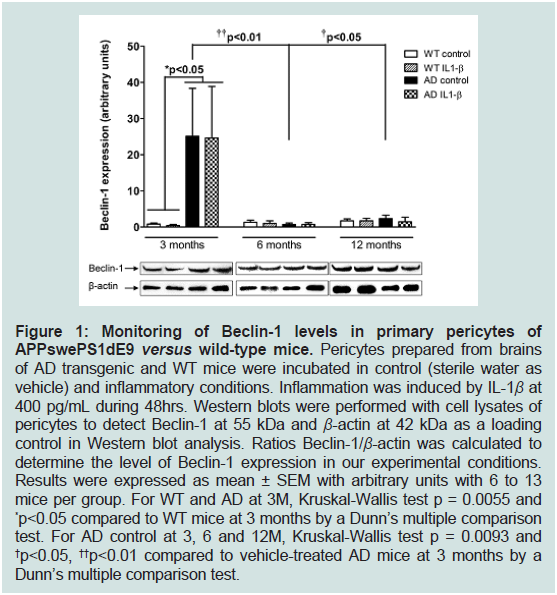

3-months old APPswePS1dE9 mice (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Monitoring of Beclin-1 levels in primary pericytes of

APPswePS1dE9 versus wild-type mice. Pericytes prepared from brains

of AD transgenic and WT mice were incubated in control (sterile water as

vehicle) and inflammatory conditions. Inflammation was induced by IL-1β at

400 pg/mL during 48hrs. Western blots were performed with cell lysates of

pericytes to detect Beclin-1 at 55 kDa and β-actin at 42 kDa as a loading

control in Western blot analysis. Ratios Beclin-1/β-actin was calculated to

determine the level of Beclin-1 expression in our experimental conditions.

Results were expressed as mean ± SEM with arbitrary units with 6 to 13

mice per group. For WT and AD at 3M, Kruskal-Wallis test p = 0.0055 and

*p<0.05 compared to WT mice at 3 months by a Dunn’s multiple comparison

test. For AD control at 3, 6 and 12M, Kruskal-Wallis test p = 0.0093 and

†p<0.05, ††p<0.01 compared to vehicle-treated AD mice at 3 months by a

Dunn’s multiple comparison test.

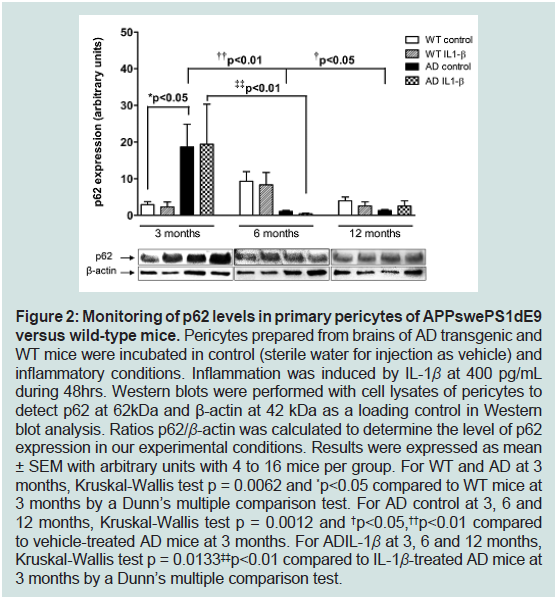

The protein p62 is an autophagic receptor which recognizes

ubiquitinylated proteins and interacts with LC3 II at the forming

autophagosome [37,42]. As for Beclin-1, results showed a great

increase of its expression levels (6.8-fold) in pericytes from 3-months

old APPswePS1dE9 mice compared to age-matched WT mice,

whereasp62 levels were significantly decreased by 18.5- and 14-

fold in pericytes prepared from brains of 6 and 12 months old

APPswePS1dE9 mice, respectively versus transgenic mice at 3 months

old age (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Monitoring of p62 levels in primary pericytes of APPswePS1dE9

versus wild-type mice. Pericytes prepared from brains of AD transgenic and

WT mice were incubated in control (sterile water for injection as vehicle) and

inflammatory conditions. Inflammation was induced by IL-1β at 400 pg/mL

during 48hrs. Western blots were performed with cell lysates of pericytes to

detect p62 at 62kDa and β-actin at 42 kDa as a loading control in Western

blot analysis. Ratios p62/β-actin was calculated to determine the level of p62

expression in our experimental conditions. Results were expressed as mean

± SEM with arbitrary units with 4 to 16 mice per group. For WT and AD at 3

months, Kruskal-Wallis test p = 0.0062 and *p<0.05 compared to WT mice at

3 months by a Dunn’s multiple comparison test. For AD control at 3, 6 and

12 months, Kruskal-Wallis test p = 0.0012 and †p<0.05,††p<0.01 compared

to vehicle-treated AD mice at 3 months. For ADIL-1β at 3, 6 and 12 months,

Kruskal-Wallis test p = 0.0133‡‡p<0.01 compared to IL-1β-treated AD mice at

3 months by a Dunn’s multiple comparison test.

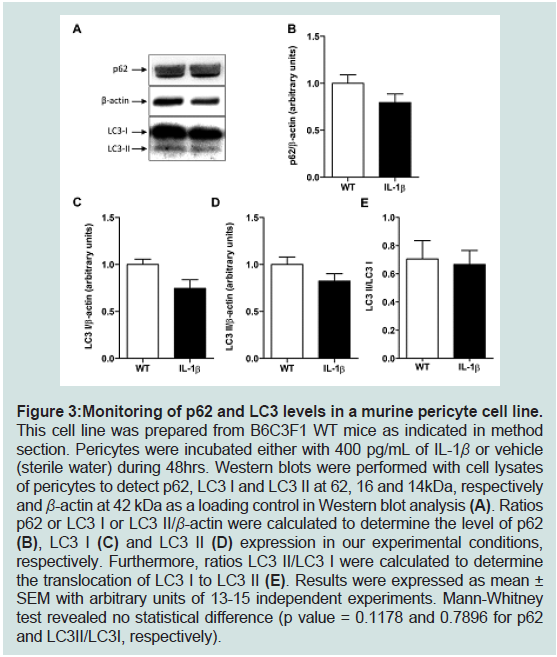

Figure 3: Monitoring of p62 and LC3 levels in a murine pericyte cell line. This cell line was prepared from B6C3F1 WT mice as indicated in method

section. Pericytes were incubated either with 400 pg/mL of IL-1β or vehicle

(sterile water) during 48hrs. Western blots were performed with cell lysates

of pericytes to detect p62, LC3 I and LC3 II at 62, 16 and 14kDa, respectively

and β-actin at 42 kDa as a loading control in Western blot analysis (A). Ratios

p62 or LC3 I or LC3 II/β-actin were calculated to determine the level of p62

(B), LC3 I (C) and LC3 II (D) expression in our experimental conditions,

respectively. Furthermore, ratios LC3 II/LC3 I were calculated to determine

the translocation of LC3 I to LC3 II (E). Results were expressed as mean ±

SEM with arbitrary units of 13-15 independent experiments. Mann-Whitney

test revealed no statistical difference (p value = 0.1178 and 0.7896 for p62

and LC3II/LC3I, respectively).

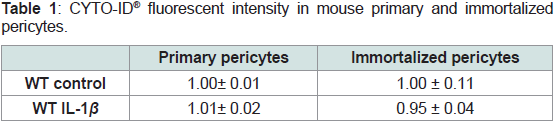

Contrary to primary microglia [1], an inflammatory environment

induced by IL-1β did not influence the levels of autophagic parameters

in primary pericytes (Figure 1 and 2). To complete these results, we

performed CYTO-ID® and LYSO-ID® assays to determine if there is an

autophagosome accumulation (CYTO-ID® and LYSO-ID® responses)

or lysosome and lysosome-like organelle perturbations and

phospholipidosis (LYSO-ID® response) at 3 months. No difference

of the fluorescent intensity was observed in primary WT pericytes

exposed to 400 pg/mL IL-1β compared to vehicle-treated pericytes

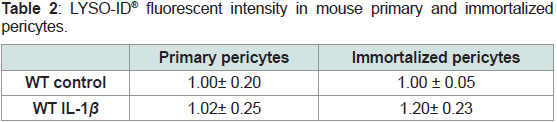

(Table 1 and 2).

Table 1: CYTO-ID® fluorescent intensity in mouse primary and immortalized

pericytes.

Pericytes were exposed to 400 pg/mL IL-1β for 48hours and CYTO-ID® dual

color reagent was added for 30 min at room temperature before being read by

fluorescence using a Varioskan Flash microplate reader. Rapamycin (1 μM)

as an inducer of autophagy and Chloroquine (10 μM) as a lysosomal inhibitor

were included as positive controls. Ratios of fluorescent intensity for CYTO-ID®

green detection reagent / fluorescent intensity for Hoechst 33342 nuclear stain

were calculated and results were normalized to control. For Rapamycin and

Chloroquine mixture, ratio was 1.32 ± 0.04.

Table 2: LYSO-ID® fluorescent intensity in mouse primary and immortalized

pericytes.

Pericytes were exposed to 400 pg/mL IL-1β for 48 hours and LYSO-ID® dual

color reagent was added for1 hour at room temperature before being read by

fluorescence using a Varioskan Flash microplate reader. verapamil (10 μM),

a lysosome-perturbation agent, is provided as a positivecontrol. Ratios of

fluorescent intensity for LYSO-ID® red dye signal /fluorescent intensity for the

blue nuclear counterstain were calculated and results were normalized to control.

For Verapamil, ratio was 1.32 ± 0.12.

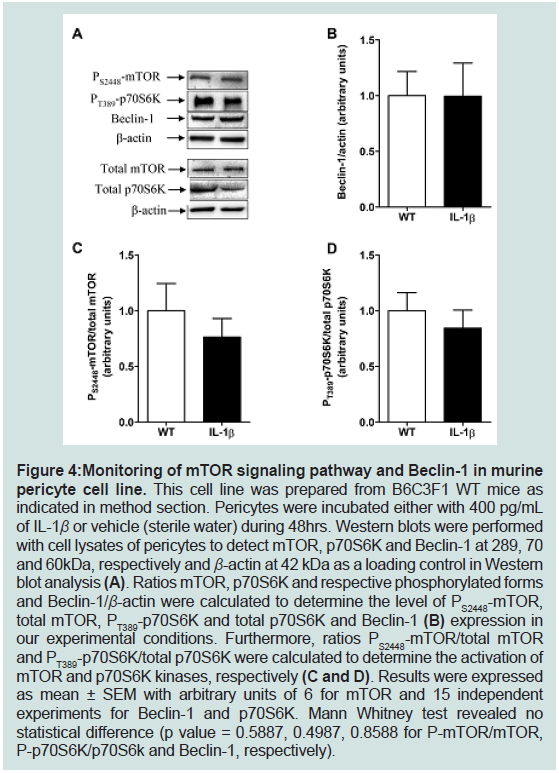

Monitoring of autophagy in mouse immortalized pericytes:

As indicated in the section of materials and methods, a murine

WT pericyte line was obtained from primary pericytes extracted from

the brains of 3-month-old B6C3F1 mice. This line allows us to obtain

more biological material than primary cells and to reduce the number

of animals in the experiments. It seemed useful to us to check whether

this line responded similarly in their autophagic components,

as mouse primary pericyte cultures in the same inflammatory

environment. As shown in figure3, IL-1β induced no modification of

p62 (panels A,B) norLC3 I and LC3 II (panels A, C to E) expression

levels. These results are also reinforced by the absence of changes in

Beclin-1 expression and in mTOR and p70S6K activations in IL-1β-

treated pericytes compared to control pericytes (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Monitoring of mTOR signaling pathway and Beclin-1 in murine

pericyte cell line. This cell line was prepared from B6C3F1 WT mice as

indicated in method section. Pericytes were incubated either with 400 pg/mL

of IL-1β or vehicle (sterile water) during 48hrs. Western blots were performed

with cell lysates of pericytes to detect mTOR, p70S6K and Beclin-1 at 289, 70

and 60kDa, respectively and β-actin at 42 kDa as a loading control in Western

blot analysis (A). Ratios mTOR, p70S6K and respective phosphorylated forms

and Beclin-1/β-actin were calculated to determine the level of PS2448-mTOR,

total mTOR, PT389-p70S6K and total p70S6K and Beclin-1 (B) expression in

our experimental conditions. Furthermore, ratios PS2448-mTOR/total mTOR

and PT389-p70S6K/total p70S6K were calculated to determine the activation of

mTOR and p70S6K kinases, respectively (C and D). Results were expressed

as mean ± SEM with arbitrary units of 6 for mTOR and 15 independent

experiments for Beclin-1 and p70S6K. Mann Whitney test revealed no

statistical difference (p value = 0.5887, 0.4987, 0.8588 for P-mTOR/mTOR,

P-p70S6K/p70S6k and Beclin-1, respectively).

We also performed CYTO-ID® and LYSO-ID® experiments

with the cell line. The fluorescent intensities were similarwhatever

conditionto primary pericyte results (Table 1 and 2).

Discussion

Autophagy dysfunction was detected in brains of AD patients in

2005 [27]. Many authors then published data validating this alteration

with a decrease in Beclin-1 level and its role in AD [36,43,44], a

blockage of autophagic flow with dysfunction of lysosomal activities

during AD in various experimental models of the disease [28,29,45].

Previous results showed that IL-1β led to a blockage of autophagy

in microglia, highly sensitive to this inflammatory stress [1]. Other

authors demonstrated the relationship between autophagy and IL-

1β stress in AD [35]. Thus, chemical modulators of autophagy as

well as gene therapy targeting autophagy related proteins offer great

potential for the AD treatment. A number of mTOR-dependent

and independent autophagy modulators have been demonstrated to

have positive effects in AD animal models and patients [28,46,47].

However, no data are available in the literature about autophagy at

the level of BBB during aging or in AD, while the BBB dysfunction in AD is largely described [16,19,48]. Studies showed that autophagy

was enhanced in middle cerebral artery occlusion/reperfusion and

oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion experiments. In these

contexts, autophagy would have either protective or detrimental

roles in BBB function and ECs [49]. Autophagy could decrease BBB

permeability and ischemic damage, but also induce apoptosis and cell

death [49].

For the first time, we observed that primary pericytes purified

from brain of APPswePS1dE9 mice showed an increase of Beclin-1,

p62 and LC3 II expression levels at 3 months compared to agematched

WT mice. Then, levels of these autophagy markers were like

those of WT mice at 6 and 12 months. These autophagy changes in

primary pericytes at 3 months revealed an activation of autophagy

with no accumulation of autophagosomes or lysosomes, indicating no

impairment of autophagic flow. At 3 months, APPswePS1dE9 mice

displayed no amyloid deposits but produced intracellular Aβ. At 6

months, extracellular Aβ was mainly depicted in cerebral parenchyma

[50]. It is known that Aβ34, a marker for amyloid clearance in

AD, was predominantly detectable in a subset of brain capillaries

associated with pericytes, while in later clinically diagnosed AD

stages, this pericyte-associated Aβ34 immuno reactivity was largely

lost [51]. BBB-associated pericytes clear Aβ aggregates via an LRP1-

dependentApoE isoform-specific mechanism with apoE4 disrupting

Aβ clearance compared to apoE3 [52,53]. One may propose that

enhanced autophagy at 3 months in these transgenic AD mice could

be explained by the proteolytic degradation of Aβ40 and Aβ42.

Contrary to primary microglia [1,35], IL-1β-induced inflammation

did not modify expression of Beclin-1, p62 and LC3 II in primary WT

or AD pericytes. Furthermore, no modification of autophagy markers

and of the mTOR signaling pathway was observed in pericyte cell

line. The concentration of IL-1β (400 pg/mL) may be questioned. It

was chosen based on our previous work on microglia where higher

concentrations led to cell death [1]. Recently, authors showed that

inhibition of the NLRP3-contained inflammasome reducedpericyte

cell coverage and decreased protein level of PDGFR β contrary to

IL-1β which is the major product of NLRP3 [54]. Concentrations

of IL-1β were 12.5 to 125 times higher than those used in our study

and authors concluded that NLRP3 activation maintained healthy

pericytes in the brain and warned of therapeutic strategies to inhibit

inflammasome [54]. Besides the relationship between NLRP3 and

pericyte survival, we can ask the question of the resistance of the

pericytes to this inflammatory stress at the autophagic level because

inflammation generally stimulates autophagy, or even blocks the flow

and leads to death. However, no data were available in the literature

about the autophagic status of pericytes in AD. In stroke and cocaine

exposure, authors showed that in pericytes autophagy was regulated

by the sigma-1 receptor signaling pathway [55,56].

For the first time, we show that autophagy is activated in primary

pericytes at 3 months. Proteolytic degradation of amyloid peptides

may explain this activation. In addition, inflammation has no impact

on autophagic flow under our experimental conditions, but data in

the literature highlighted that NLRP3 activation might be essential

to maintain pericytes in the healthy brain. Further experiments will

be needed to understand the relationship between autophagy and

inflammation in pericytes.

Acknowledgement

This work has benefited from the facilities and expertise of

PREBIOS platform (University of Poitiers, France). The authors

thank Damien Chassaing (EA3808 Neurovascular Unit and Cognitive

Disorders, University of Poitiers) for his technical skills and the

Fondation Claude Pompidou for financialFrançois A, Terro F, Janet

T, Bilan AR, Paccalin M, et al. (2013) Involvement of interleukin-

1β in the autophagic process of microglia: relevance to Alzheimer’s

disease. J Neuroinflammation 10: 915.