Journal of Pediatrics & Child Care

Download PDF

Case Report

Distal Femoral Physiolysis in a Myelomeningocele Patient - Early and Accurate Diagnosis

Martin AR1,2, Syros A2 and Payares-Lizano M1*

1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Nicklaus Children’s Hospital,

Miami, FL 33155, USA

2Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL 33136,

USA

*Address for Correspondence:

Payares-Lizano M, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery,

Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, Miami, FL 33155, USA; E-mail: mpayaresmd@gmail.com

Submission: 09 September, 2021

Accepted: 04 May, 2022

Published: 09 May, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Martin AR, et al. This is an open access

article distributed under the Creative Commons Attr-ibution

License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is

properly cited.

Abstract

Background: Neurogenic physiolysis is the spontaneous widening,

inflammation, and fracture of long bone physes in children with spinal

cord defects. This condition is also referred to as epiphysiolysis and is

often missed by parents and physicians alike due to the lack of typical

fracture symptoms like pain and deformity.

Case Presentation: We present the case of a 5-year-old lumbarlevel

myelomeningocele patient who presented to the emergency

department with edema, warmth, and erythema of the knee joint, and

was later found to have elevated inflammatory markers concerning

for infection. After a thorough workup helped to rule out infection and

other life-threatening illness, the patient was successfully treated for

physiolysis of the distal femur with cast immobilization.

Conclusions: General pediatricians and orthopaedic specialists

should remain vigilant in recognizing physiolysis in this patient

population. Missed or delayed diagnosis may lead to iatrogenic

harm and can have negative long-term effects on patient’s physical

development and independence.

Abbreviations

MMC - Myelomeningocele, HKAFO - Hip-knee-ankle-footorthosis,

PT - Physical therapy, ESR - Erythrocyte sedimentation rate,

CRP - C-reactive protein, AP - Anterior-posterior, MRI - Magnetic

resonance imaging

Introduction

Children with congenital spinal cord defects like

myelomeningocele (MMC) are often times paraplegic and insensate

in the lower extremities. Low bone mineral density and lack of pain

feedback put them at high risk of atraumatic fractures in the lower

extremities, seen in 10-30% of patients with myelomeningocele [1,2].

Spontaneous isolated long bone physeal fracture or physeal widening

in spina bifida patients, referred to as physiolysis or epiphysiolysis,

is thought to occur secondary to a combination of repetitive

microtrauma, musculoligamentous imbalance, and osteopenia

[3,4]. The proximal tibial and distal femoral physes are most often

affected. The most common presenting symptom is a painless, warm,

and swollen joint, oftentimes first noticed by a parent [2,3,5]. These

patients, and their parents, often do not recall any precipitating event.

The lack of pain and history of trauma not only delays diagnosis

but often leads to the misdiagnosis of infection, possibly subjecting

patients to iatrogenic harm secondary to invasive diagnostic tests,

as well as continued repetitive microtrauma due to the delayed

diagnosis [3]. The physeal widening seen on plain films of patients

with physiolysis is similar to that seen in patients with scurvy, rickets,

syphilis, and osteomyelitis [5,6]. Thus, early and accurate diagnosis

is important.

We present the case of a child with lower lumbar spina bifida

who presented with an atraumatic warm and swollen knee, found to have distal femoral physiolysis. Due to her lack of traumatic history,

compounded with joint swelling and redness, the initial workup was

for infection. This case demonstrates the importance of recognizing

the unique presentation physiolysis in patients with spina bifida and

avoiding a delayed or missed diagnosis.

Case Presentation

A 5-year-old female with a history of lower lumbar level

myelomeningocele had been followed in our multidisciplinary spina

bifida clinic since age 5 months. Her managed conditions included

hydrocephalus, bowel and bladder incontinence, and bilateral lower

extremity paralysis. She had been using a hip-knee-ankle-footorthosis

(HKAFO) since age 2 and was able to use a stander for short

periods during physical therapy (PT) but was otherwise wheelchairbound.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, her PT sessions had been

cancelled for several months prior to presentation. The patient’s

mother brought her into the pediatric emergency department over

the weekend with a chief complaint of left knee swelling noticed

that morning. There was no recent history of trauma or travel. On

exam, the left knee was moderately swollen with a large effusion,

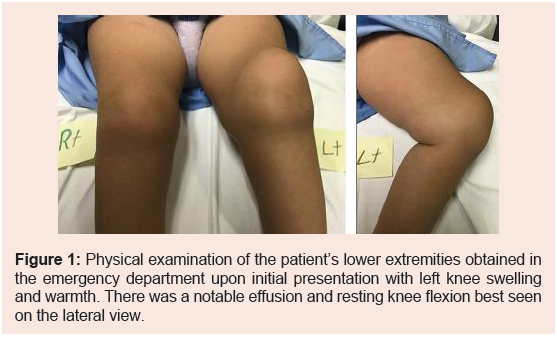

erythematous, and warm (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Physical examination of the patient’s lower extremities obtained in

the emergency department upon initial presentation with left knee swelling

and warmth. There was a notable effusion and resting knee flexion best seen

on the lateral view.

There was no sensation below the proximal thighs and no motor

function below the waste on bilateral lower extremities, as per baseline.

The knee was grossly stable on exam with full range of motion. Plain

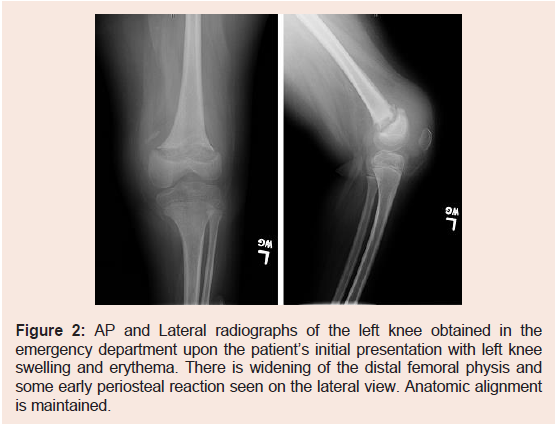

X-Ray films of the left knee demonstrated distal femoral physeal

widening and periosteal reaction (Figure 2).

Figure 2: AP and Lateral radiographs of the left knee obtained in the

emergency department upon the patient’s initial presentation with left knee

swelling and erythema. There is widening of the distal femoral physis and

some early periosteal reaction seen on the lateral view. Anatomic alignment

is maintained.

Vital signs and labs at that time were within normal limits. The

patient was placed into a long leg splint by the orthopaedic resident

on call and scheduled for outpatient follow up. Three days later,

the patient presented to the multidisciplinary spina bifida clinic for

follow up. She again was noted to have a painless large effusion of the

left knee. She was converted to a long leg cast and new x-rays were

obtained. There was noted to be no significant change in alignment

and osteolysis of the distal femoral physis with periosteal reaction.

Salter-Harris I fracture of the distal femur was suspected. Magnetic

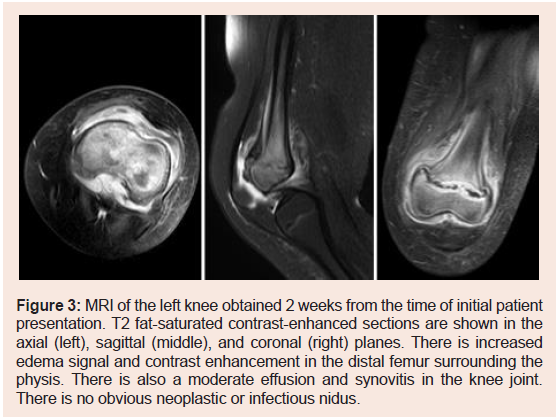

resonance imaging (MRI) of the left knee with and without contrast

was obtained 2 weeks from the time of presentation to further

delineate the process. MRI showed inflammation throughout the

distal femur and synovitis of the knee joint (Figure 3).

Figure 3: MRI of the left knee obtained 2 weeks from the time of initial patient

presentation. T2 fat-saturated contrast-enhanced sections are shown in the

axial (left), sagittal (middle), and coronal (right) planes. There is increased

edema signal and contrast enhancement in the distal femur surrounding the

physis. There is also a moderate effusion and synovitis in the knee joint.

There is no obvious neoplastic or infectious nidus.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate at that time was elevated at 53

and C-reactive protein was borderline at 3, raising some concern for

infection. Knee arthrocentesis was performed and resulted in a normal

cell count and negative cultures. At this point, we had comfortably

ruled out the possibility of osteomyelitis or septic arthritis, and

the diagnosis was confirmed as left distal femoral physiolysis. The

patient was managed in well-padded cast immobilization of the left

lower extremity for 2 months and then was transitioned to a custom

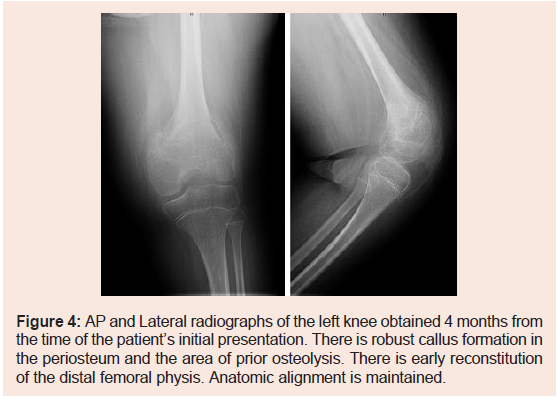

HKAFO for another month. X-rays obtained 4 months from the time

of onset demonstrated robust callus formation at the distal femoral

metaphysis and early reconstitution of the physis (Figure 4).

Figure 4: AP and Lateral radiographs of the left knee obtained 4 months from

the time of the patient’s initial presentation. There is robust callus formation in

the periosteum and the area of prior osteolysis. There is early reconstitution

of the distal femoral physis. Anatomic alignment is maintained.

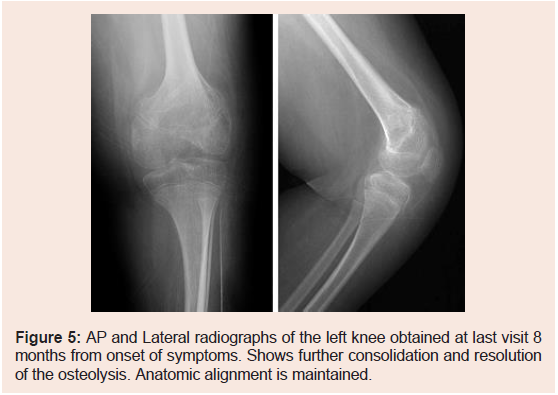

The patient was then cleared for return to routine physical

therapy without orthosis. At latest follow-up, 8 months after onset,

the patient was now 6 years old and was doing very well without any

recurrent left knee symptoms. Her function had returned to baseline.

Final X-rays demonstrated complete resolution of osteolysis, further

consolidation of callus, and maintenance of anatomic alignment

(Figure 5).

Discussion & Conclusion

The early recognition of physeal fractures in pediatric patients

with MMC spina bifida is crucial in improving patient outcomes

and avoiding long term consequences affecting their mobility and

independence [2,3,7]. The delayed recognition of injury by parents in

insensate patients can be further compounded by a physician’s missed or delayed diagnosis. This delayed diagnosis can turn relatively minor

injuries into unstable fractures due to repetitive microtrauma, which

can ultimately lead to complications such as premature physeal arrest,

angular deformity, or non-union [3,8]. Chronic stress on a fractured

physis can lead to physiolysis with widening and delayed healing,

which should be treated with immobilization of the extremity as

soon as possible [2,3]. Initial workup with plain radiographs is

the key in making the correct diagnosis, characterized by physeal

widening and periosteal reaction without angular or translational

deformity. However, these radiographic findings can often resemble

osteomyelitis or sarcoma, and should be closely monitored with serial

exams [2,7,9].

Furthermore, accurately diagnosing physiolysis in patients

with spina bifida is challenging due to the presentation of systemic

symptoms like fever, leukocytosis, and elevated inflammatory

markers (ESR, CRP), which often lead to the mistaken diagnosis of

cellulitis, osteomyelitis, or septic arthritis [2,3,10,11]. These symptoms

and lab findings typically resolve with immobilization and close

observation and should not always indicate advanced imaging or

invasive procedures like arthrocentesis. However, if patient follow-up

is limited, early and thorough diagnostic workup may be indicated to

rule out more severe, life-threatening disease. MRI with and without

gadolinium contrast can help identify the characteristic physeal

widening of physiolysis with islands of calcification, irregularity of

the zone of provisional calcification, and enhancement of the adjacent

epiphysis and metaphysic [8].

General pediatricians and orthopaedic specialists should remain

vigilant in recognizing the unique presentation of physiolysis in pediatric patients with spina bifida. Missed or delayed diagnosis may

lead to iatrogenic harm and can have negative long-term effects on

patient’s physical development and independence.