Journal of Pediatrics & Child Care

Download PDF

Research Article

Evaluating the Feasibility and Utility of an Educational Webinar Series on Autism for Pediatric Primary Care Providers: A Pilot Study

Ayala-Brittain ML1, Bergez-Cohn KC1, Mire SS1,2, Ahmed KL4, Berry LN3,4, Monteiro SA4, Strickland DC5 and Goin-Kochel RP3,4*

1Department of Psychological, Health, & Learning Sciences,

University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA

2Department of Educational Psychology, Baylor University, Waco,

TX, USA

3Psychology Section, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of

Medicine, Houston, TX, USA

4Meyer Center for Developmental Pediatrics &Autism, Texas

Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, USA

5DiagnoseFirst, Raleigh, NC, USA

*Address for Correspondence:

Goin-Kochel RP, Psychology Section, Department of

Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA;

Telephone: 832-824-3390; Facsimile: 832-825-3399;

E-mail: kochel@bcm.edu

Submission: 10 February, 2023

Accepted: 24 March, 2023

Published: 29 March, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Ayala-Brittain ML, et al. This is an open

access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution

License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution,

and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work

is properly cited.

Abstract

Background: Parents of children later diagnosed with autism

spectrum disorder (ASD) frequently raise concerns about their

child’s behavior and development with their pediatric primary

care providers (PPCPs). However, few PPCPs make timely referrals

to ASD specialists following positive ASD-screening results, and

even fewer evaluate for ASD themselves-actions that contribute

to the ASD-detection gap (i.e., the time span between first

concerns and eventual diagnosis). Some literature suggests that

PPCPs’ lack of knowledge about and/or confidence in managing

ASD/suspected ASD contributes to referral and diagnostic delays.

Methods: To evaluate the utility of an online educational

platform to guide PPCPs in the early identification and

management of ASD, we invited PPCPs within a hospital-affiliated,

pediatric-practice network to participate in a three-part webinar

series on screening, diagnosis, and referral practices for ASD.

Each webinar lasted approximately one hour and conferred one

continuing medical education credit. Pre- and post-test surveys

were imbedded within each webinar and solicited open-ended

feedback.

Results: Among 288 potential participants, 37 (12.8%)

completed the first of three webinars and 28 (9.7%) completed all

three. All pre-post knowledge and confidence scores increased

significantly for each webinar (all p ≤ .001). Participants’ openended

feedback was largely positive; most reports cited

information about the M-CHAT-R/F follow-up interview (Screening

webinar), videos contrasting neurotypical/atypical behaviors

(Diagnosis webinar), information on testing/medical workup

(Referral webinar), and referral resources (Referral webinar) as the

most helpful aspects.

Conclusion: The PPCP response rate was relatively low, despite

efforts to increase engagement with the webinars. This may

have resulted from lack of time, a frequently reported barrier to

PPCPs’ participation in educational activities. Among those who

participated, significant knowledge and confidence gains were

observed, and provider feedback was overwhelmingly positive.

Findings have implications for the development/refinement

of such webinars for broader distribution, as well as alternate

learning platforms to increase utility.

Keywords

Autism Spectrum Disorder; Pediatric Primary Care;

Pediatricians; Knowledge and Confidence

Introduction

Diagnostic prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has

dramatically increased in the United States (U.S.), with the latest

figure estimating 1-in-44 children have ASD [1]. Although core

symptoms of ASD are usually observed within the first 2 years of life,

only 42% of children with ASD are evaluated before age three [2]. Currently, the average age at ASD diagnosis in the U.S. is around

4 years, meaning many children are missing out on important

interventions during the window of opportunity when they are most

impactful [3]. Early diagnosis is key to families’ access to intensive

behavioral interventions that promote developmental outcomes

across domains (language skills, adaptive-functioning skills, social

skills) and throughout the lifespan. However, the present delay of

approximately 2.7 years between initial parent concerns and ASD

diagnosis (i.e., “the ASD-detection gap”) is especially concerning

because diagnostic delays or inaccurate diagnoses can limit or

prevent access to these services. Moreover, these delays maybe even

greater for children from under-resourced or minoritized groups

[4], representing a social injustice and highlighting the necessity of

increasing access to timely diagnostic services for all children with

suspected ASD. Bolstering access through existing points of contact

in primary care represents a potentially effective mechanism for

accomplishing such aims.

The Role of Pediatric Primary Care Providers in Early ASD Identification:

During the first five years of a child’s life, pediatric primary care

providers (PPCPs) are typically the first point of contact for families

when developmental concerns arise, which coincides with the critical

years for an ASD diagnosis (Committee on Children with Disabilities

[CCD], 2001; [5-7]. Because of the frequency of well-child visits and

parent familiarity with pediatric offices, PPCPs are essential to early,

accurate ASD identification and are considered a gateway to early intervention services. PPCPs serve multiple roles in this process,

including responding to parents’ initial concerns, recognizing atrisk

children though routine developmental surveillance, diagnosing

ASD, referring children to appropriate specialists, and helping

caregivers advocate for their children [7,15]. Consequently, the

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) provides specific guidelines

for PPCPs with regard to identifying, diagnosing, referring, and

treating children with ASD within the primary care setting [8].Screening Recommendations and Practices Following Positive Screens:

Current AAP guidelines indicate that (a) general developmental

surveillance should take place at the 9-, 18-, 24-, and 30-month

well-child visits to determine whether a child is meeting expected

milestones, and (b) ASD-specific screening should occur at 18- and

24-months to identify children whose symptoms may emerge or

become more apparent during the second year of life (CDC, 2019).

Though research supports the validity of ASD-specific screening

tools in primary care, their use among PPCPs has ranged from as low

as 8% to as high as 60% in recent years [9]. Barriers to use of the

Modified Checklist of Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-Up

(M-CHAT-R/F, one of the most commonly used ASD screeners, have

included an inability to complete necessary follow-up interviews,

time constraints, and provider concerns about false-negative screens

[10]. Despite these barriers, PPCPs in hospital-affiliated pediatric

practice networks have high rates of M-CHAT-R/F screening [11]. In

one of these studies, 93% and 82% of eligible children received ASD

screening at their 18- or 24-month well-child visits, respectively; in

another, 91% of children were screened with the M-CHAT-R/F at

well-child visits between the ages of 16 to 24 months [12].If a child screens positive (i.e., higher likelihood of ASD) and/or

if a PPCP observes concerning symptoms, AAP guidelines suggest

several concurrent steps [7], including referrals for comprehensive

evaluation, audiology evaluation, and early intervention services.

PPCPs should not wait for a definitive ASD diagnosis to make

referrals [7,13]; following this guideline helps to expedite intervention

to address developmental concerns while simultaneously exploring

specific diagnostic considerations, as well as ruling out possible

hearing loss. Yet recent studies suggest that referrals from pediatricians

to ASD specialists are not happening as frequently as recommended.

Monteiro and colleagues (2019) found that even though rates of

ASD-specific screening were high in their study, only 31% of children

who screened positive were referred for ASD specialist evaluation.

Moreover, among these screen-positive children, PPCPs referred

only 20% to ECI and 16% to private therapy (12% were already

receiving services). These results are similar to those of Wallis and

colleagues (2020) who found that 40.2% of children received at least

one recommended referral (i.e., early intervention, audiology, and

comprehensive ASD evaluation); however, only 3.7% received all

recommended referrals.

Reasons for Referral and Diagnostic Inactions Following Positive Screening:

Considering that some interventions are predicated on the

ASD diagnosis, it is critical to understand where potential obstacles

lay in PPCPs’ screening, diagnostic, and referral workflows so that they can be addressed. PPCPs themselves report lacking knowledge

of treatment options, insufficient training in ASD diagnosis and

treatment, ambiguity regarding their role in ASD-specific care, and

difficulty with care coordination [14-16]. Some research indicates

that, although PPCP knowledge of ASD symptomology is high (i.e.,

recognizing language communication problems, social interaction,

limited area of interest), a majority of PPCPs (61%) report difficulty

facilitating connections between families of children with ASD

and community services [17], as well as having discussions about

recommended next steps. PPCPs also consistently report lacking

knowledge about school-based services (Hastings et al., 2014) - a

critical gap because so many families rely heavily on services offered

through their local school districts [18].In addition to lacking knowledge about available services and

supports, PPCPs also hold a number of beliefs about ASD that may

affect their referral/diagnostic actions. Some providers endorse

negative attitudes toward the utility and necessity of validated

screening tools and believe that developmental surveillance alone

is sufficient for ASD identification [19,20]. Other providers claim

they do not refer children with suspected ASD for a comprehensive

evaluation so as to avoid negative emotional reactions from parents.

Many PPCPs report difficulty reconciling the AAP mandate to screen

and diagnose ASD early with a lack of knowledge about treatment

options and resources available for this population [21]. Moreover,

because of insufficient training, many PPCPs report low confidence

in their ability to provide care for children with ASD, as well as low

self-efficacy in the ASD-referral process [4-6]. Lacking knowledge

and confidence in these areas may help explain PPCPs’ poor followthrough

in making necessary referrals to autism specialists, thereby

contributing to the ASD-detection gap.

ASD-Specific Education and Supports for Pediatricians:

One means of addressing PPCPs’ role in ASD identification is

through training that improves their ASD-specific knowledge and

confidence. A study of PPCPs in Brazil found that an educational

training program in ASD identification, diagnosis, and treatment

significantly improved PPCPs’ knowledge about ASD and was

associated with increased referral patterns four months after the

training program ended, with providers referring six times as many

suspected cases of ASD [22]. ASD-specific training programs have

also had significant effects when implemented with medical residents.

In one such study, web-based learning activities, combined with

hands-on training, resulted in 95% of residents reporting increased

confidence identifying ASD within the primary care setting (Hine

et al., 2021). Web-based or online training programs may be

particularly valuable in offering a free and flexible way for healthcare

providers to access such information, and an internet search quickly

reveals that the number of such course offerings abounds. However,

there is limited evidence of their quality and utility. It is not clear

how often such programs are actually being used, how they are

valued by the intended audiences, and whether they influence

providers’ knowledge and confidence about ASD and subsequent

clinical practices. For example, one study found that health care

professionals who held inaccurate perceptions about their role within

the ASD diagnostic process were less likely to acknowledge their

need for such information/supports and advocate for training [13], suggesting that those who are most in need of this information may

be unlikely to seek it on their own. Furthermore, because of the time

and costs involved with developing and updating online training

materials, it is important to examine whether this is an acceptable

educational platform for PPCPs. To that end, the current pilot study

sought to evaluate (a) PPCPs’ use and acceptability of an introductory

educational webinar series on ASD-screening, diagnosis, and referral

practices; and (b) potential improvements in PPCPs’ knowledge and

confidence about ASD-screening, diagnosis, and referral practices

following their participation.Methods

Participants:

Participants were PPCPs from a network of 51 primary care

clinics associated with a large hospital system in Houston, Texas.

Email invitations to PPCPs were sent by the study team in two waves

to 263 providers within the network (Wave 1 [n = 132], Wave 2

[n = 131]). A third group of providers (n = 25) from an integrated

primary care clinic were also invited following a specific request

from their group for training in ASD diagnosis, thus creating a total

sampling pool of 288 providers. Because these participants were

employees of the hospital system, we did not solicit demographic

or otherwise potentially identifiable information. This strategy

helped to maintain privacy, reduce time burden on participants and

encourage participation, and further mimicked real-world training

opportunities (i.e., outside the research context).Materials:

This study was reviewed and approved by the Internal Review

Board at Baylor College of Medicine. The three-part webinar series

was designed by the study team to educate PPCPs in Screening,

Diagnosis, and Referrals for ASD. This series was developed with

input from a paid consultant who had extensive expertise in ASD

screening with the M-CHAT-R/F and in partnership with Diagnose

First (diagnosefirst.com), a web-based resource that provides video based

education and instruction in early ASD detection and ASD

diagnosis. Each of the three webinars included evidence-based

content that was consistent with current AAP-practice parameters

for screening and management of ASD. The Diagnosis webinar,

in particular, focused on ASD core symptoms and included high quality

videos selected from Diagnose First’s extensive ASD video

library that contrasted neurotypical and ASD-related behaviors in

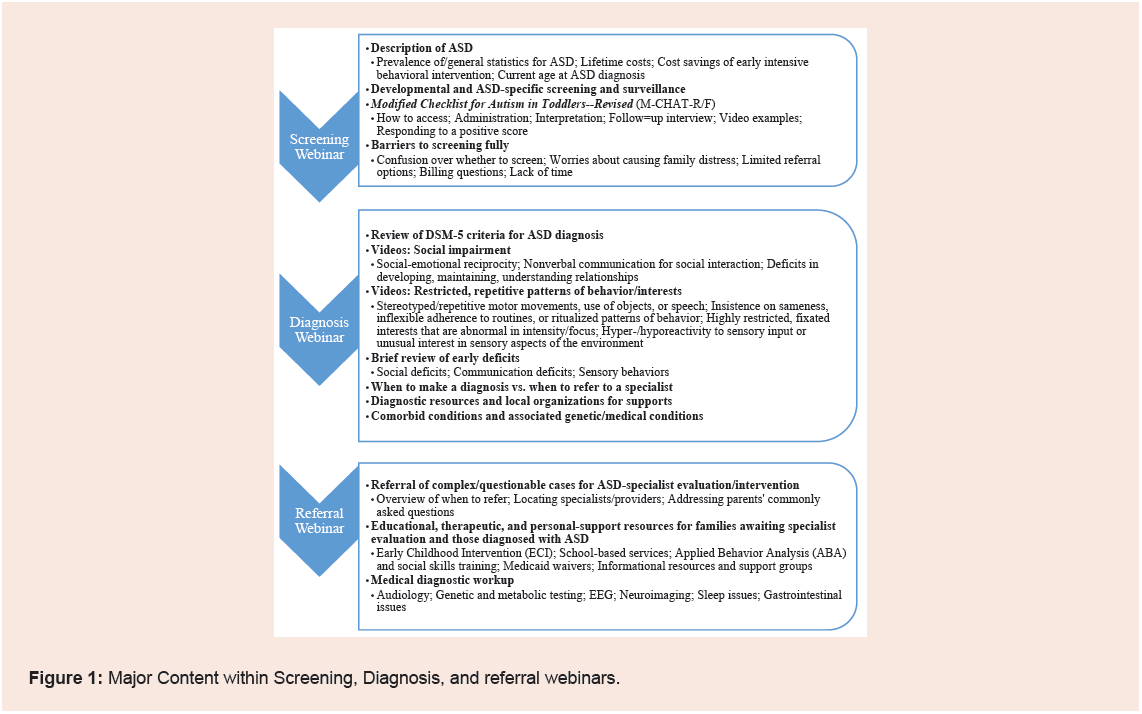

young children. An overview of the content for each webinar is in

Figure 1. The webinar series was hosted on Diagnose First’s web-based

platform, which required users to request a free, unique login

to access the site’s content. Each webinar was self-paced, lasted

approximately one hour, and conferred one hour of continuing

medical education (CME) credit, as approved through the hospital’s

Office of Continuing Medical Education.Electronic pre- and post-webinar questionnaires were developed

by the study team and embedded within each webinar. Each

questionnaire contained 10 items, three of which assessed potential

changes inself-reported knowledge of and confidence in ASDscreening,

-diagnosis, and -referral practices. Response options

to these items were on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from

“1-Not at all” to “-Extremely,” with higher scores indicating greater

knowledge/confidence. The remaining items on each survey queried other content presented in each webinar; because these content items

were not part of a validated instrument, they were collected to inform

future efforts only. Pre- and post-survey items for each webinar

were identical, yet item wording was tailored to match the webinar’s

topic (Screening, Diagnosis, or Referral). Additionally, post-test

questionnaires included open-ended text boxes for provision of

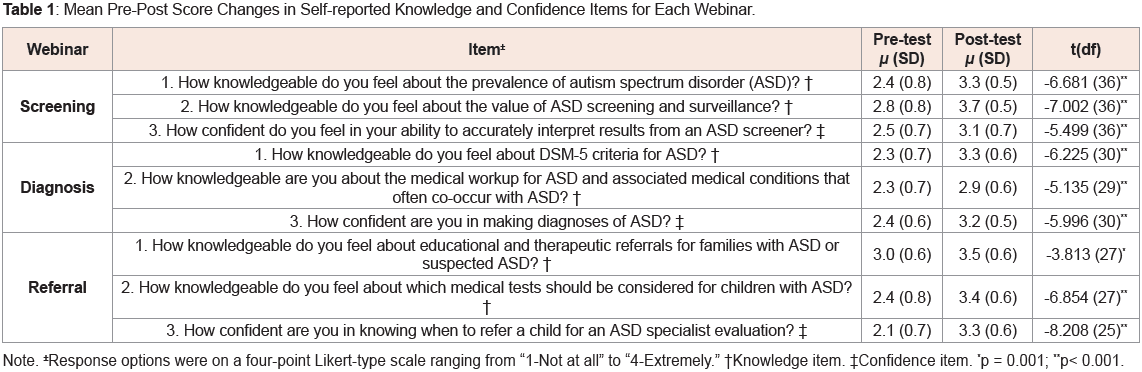

optional feedback. Table 1 contains the self-reported knowledge and

confidence items that were the primary focus of this study.

Table 1: Mean Pre-Post Score Changes in Self-reported Knowledge and Confidence Items for Each Webinar.

Procedure:

Potential participants received an initial email invitation,

followed by up to three reminder emails at two-week intervals. Each

invite/reminder email included instructions for requesting their

unique login information to access the webinar website. Once logged

in, participants were authorized to view the Screening, Diagnosis, and

Referral webinars, with controls enabled that mandated their viewing

in that order because content built on the preceding webinar. Before

and after each webinar, participants received the pre- and post-test

questionnaires; a participant could not view a given webinar without

first completing the pre-test for that webinar. Likewise, a participant

must have completed the prior webinar’s post-test in order to access

the next webinar’s pre-test. Following completion of each post-test

questionnaire, participants had the option to print a CME certificate.

Once participants completed the Referral post-test, they could

download and/or print the entire webinar series for future reference.

Overall, we designed the participation process to mimic training

opportunities outside the context of research, where institutional

mandates and monetary incentives are typically not encountered.To compare pre-post changes across all self-reported knowledge

and confidence scores for each webinar, paired-samples t-tests were

used, as these were ordinal variables with no “right” versus “wrong”

responses. Participants’ open-ended feedback was initially reviewed

for possible thematic analysis; however, because of the brevity

of these responses and clear emotional valence, content analysis

was applied to categorize participants’ statements as positive (i.e.,

praised/found value) [27], negative (i.e., criticized/disagreed with),

constructive (i.e., provided recommendations), and/or neutral (i.e.,

impartial comment). If a statement included more than one type of

content, then it was classified in each appropriate category (i.e., a

statement could have both positive and constructive components and

be counted in each of these categories).

Results

Overall, 37/288 providers (12.8%) completed the Screening

webinar; 31/288 providers (10.8%) completed the Diagnosis webinar;

and 28/288 (9.7%) providers competed the Referral webinar.

However, even in this small sample, paired samples t-tests revealed

statistically significant pre-post increases (p ≤ .001) across all selfreported

knowledge and confidence scores for each webinar (see

Table 1). Similarly, disagreement with the statement that “Only

specialists are able to diagnose ASD, and primary care providers do

not have the training to make an accurate diagnosis,” significantly

increased from pre- to post-test (t[29] = -2.757, p = 0.01).

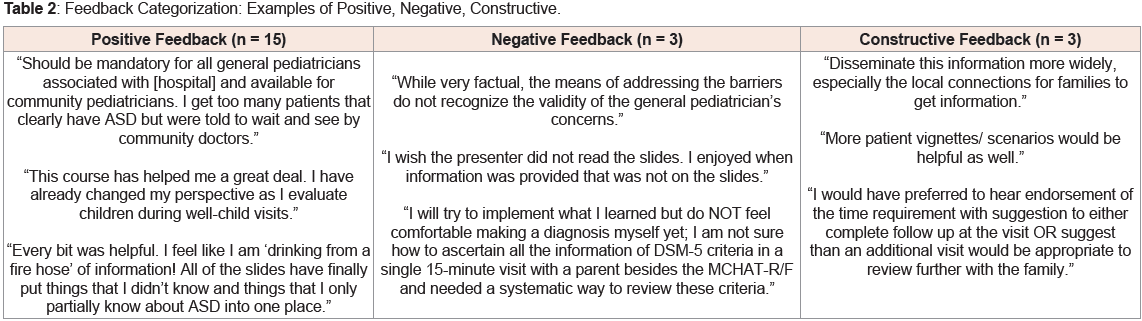

A total of 19 PPCPs provided open-ended feedback about the

webinars; 15 (78.9%) included positive sentiments. Three responses

(15.8%) contained negative feedback; five (26.3%), constructive

feedback; and three (15.8%), neutral feedback (see examples in Table 2). One participant recommended that the webinar series, “…should

be mandatory for all general pediatricians associated with [hospital],”

and two participants recommended broader distribution of the

webinars to community pediatricians. Four participants requested a

page of resources (e.g., .pdf or Word document), and one requested a

copy of the slides. Two of the comments categorized as neutral were

related to technical issues and one was a comment about Epic (the

electronic health record [EHR] used by the network of practices).

In terms of the most helpful content/information in each webinar,

the most common responses were (a) M-CHAT-R/F follow-up

interview for the Screening webinar (50.0%); (b) videos contrasting

neurotypical/atypical behaviors for the Diagnosis webinar (57.1%);

and (c) testing/medical workup (57.1%) and referral resources

(57.1%) for the Referral webinar.

Discussion

We created an online educational program to educate PPCPs on

ASD-screening, diagnosis, and referral practices and then evaluated

provider use, acceptability, and potential improvements in PPCPs’ selfreported

knowledge and confidence about these practices following

their participation. An important observation with respect to use

was the low response rate. Our research design (a) included multiple

reminders as a means to encourage participation; (b) extended

recruitment beyond the targeted study-close date; (c) incentivized

participants with one hour of CME credit per webinar; and (d) enabled

downloading of each webinar as a take-away resource. We selected

a study design that mimicked real-world training opportunities,

with no institutional requirements to complete the webinars and no

financial incentives-essentially, an “if you build it, they will come”

approach. Despite efforts to increase participation rates, our sample

size remained small. This is particularly notable because those in the

integrated primary care clinic specifically requested training in ASD

diagnosis, yet only a handful participated. It is possible that many

providers simply could not find the time, as pediatricians frequently

report time constraints as barriers to providing ASD-specific support

and care. Additionally, the requirement to complete all aspects of

the previous webinar (i.e., pre-post measurements) before accessing

the next webinar may have deterred PPCPs from completing the

series. Although we included this requirement so that our content

sequentially built upon itself to reinforce key messages and align

with clinical practice (i.e., screening diagnosis referral), it may have

exasperated providers who were only interested in specific content

materials (i.e., referral information, medical workup). It also limited

our pool of participants for the Diagnosis and Referral webinars to

those who completed the Screening webinar. This is an important take

away, as many providers want more information about ASD (Carbone

et al., 2020), which emphasizes a critical need to understand how

providers want to receive this information. Interestingly, there was

relatively little drop off in participation from one webinar to the next;

31/37 (83.7%) who participated in the Screening webinar completed

the Diagnosis webinar, and 28/31 (90.3%) who participated in the

Diagnosis webinar completed the Referral webinar. Such continued

engagement may reflect providers’ acceptability of the series once

they began; though it is also likely that those who began the series in

the first place were those most interested in the content offered [28].

Despite our relatively small sample, results demonstrated that a brief (i.e., three 1-hour sessions) and convenient (i.e., self-paced and

available on-demand) webinar series on ASD screening, diagnosis,

and referral may be an effective way to educate PPCPs on these topics.

Participants showed measurable gains in self ratings of knowledge

and confidence in managing ASD following each of the webinars.

Also, more providers moved from thinking that only specialists could

diagnose ASD to recognizing that PPCPs could make the diagnosis

themselves. This is encouraging, as some providers who may have felt

that ASD diagnoses were out of their scope of practice may now feel

empowered to make the diagnosis in clear cases, thereby expediting

families’ next steps in accessing intervention services. Earlier research

suggested that, compared to other medical specialists who may

commonly see individuals with ASD (e.g., psychiatrists), PPCPs did

not differ in their knowledge about DSM criteria for ASD (Heidgerken

et al., 2005). Therefore, it is possible that providing information that

enhances PPCP confidence in their application of this knowledge

could facilitate clinical actions that lead to earlier ASD diagnoses

Among those who offered open-ended feedback, most of their

comments were complimentary, with many pointing out that the

materials were helpful, informative, and should be made available to

other pediatricians. Information about the M-CHAT-R/F follow-up

interview, videos in the Diagnosis webinar, and guidance regarding

medical workup and referrals were cited as the most valuable aspects.

PPCPs’ preference for diagnostic information and referral practices

are consistent with previously reported learning collaboratives

[6]. Interestingly, many PPCPs in this study indicated no prior

knowledge of the follow-up interview and/or a desire for more

information on how to obtain/administer it. While the M-CHATR/

F was always intended as a two-part screener [29], the majority of

pediatricians do not use the follow-up interview [8]. It is not clear

how this interview becomes separated from the initial screening

questions during clinical implementation, but our results suggest an

interest among some PPCPs to include it in their screening practices.

Pediatric clinics should evaluate whether they currently support

follow-up practices that enhance specificity of ASD-screening tools,

which may subsequently help providers feel more confident in their

referral actions.

Constructive and negative comments shared by participants

provided important considerations for future work to enhance/expand

educational tools and increase providers’ engagement in training.

A few participants made specific recommendations for improving

content, as well as shared their hesitation about implementing the

follow-up interview after a positive screen; both should be addressed

in updates to the webinars prior to subsequent distribution. The

recommendations to make the webinars more widely accessible

suggest that developing template presentations with information

tailored to a specific locale may increase generalizability and utility.

Additionally, participants were given the option to download and use

the webinar slides as a reference or resource for families they serve;

however, some may not have realized that they had this option, so

clarifying this feature and/or providing some instructions on this

process may be helpful [30-33].

Limitations and Future Directions

While this pilot study demonstrated the utility of an educational

webinar series for enhancing PPCPs’ knowledge and confidence in ASD-screening, diagnostic, and referral practices, there are

limitations to note. One is that our response rate was low; rendering a

relatively small sample that may not be reflective of the broader group

of PPCPs in the sampling pool. Notably, this study was conducted

prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it is possible that

learning preferences may be different now in the wake of increased

reliance on/familiarity with remote-engagement platforms. A second

limitation is that our questionnaires were not validated tools and were

designed to be extremely brief to encourage participant retention;

as such, they were limited in their range of content and likely do

not reflect a comprehensive assessment of what PPCPs learned

about ASD. A review of literature that included assessment of ASD

knowledge revealed no standardized approach or strong measure

of this construct, and there is a need for improved tools that are

cross-culturally relevant with corresponding content [11]. For this

reason, our focus in the current study was on PPCPs’ self-reported

knowledge and confidence ratings in the management of ASD.

Fourth, we do not know whether participation in the webinars led

to changes in providers’ screening, diagnostic, and referral behaviors

in their practices, although we intend to examine these actions in

subsequent work. Previous research in health professions suggests

that knowing does not always give rise to doing [17]. Therefore,

educational strategies alone may be insufficient to prompt changes in

practice. However, other research has observed changes in screening

and referral practices after educational interventions, such as ECHO

Autism [22]. As such, it will be valuable to follow the screening,

diagnostic, and referral practices of PPCP participants and compare

those to the practices of non-participant providers in the network.

Finally, our solicitation of open-ended feedback about the webinars

yielded brief comments from a relatively small number of PPCPs.

It is possible that a different methodological approach (e.g., indepth

interviews, focus groups) would yield data for more intensive

investigation of PPCPs’ experiences/recommendations regarding

provider education/training in the identification and management of

ASD.

Considering that participating PPCPs demonstrated important

self-reported knowledge and confidence gains as a result of their

participation in the webinars, further research should (a) explore

and compare the utility, acceptability, and efficacy of alternate ASDtraining

platforms for PPCPs; (b) develop and include validated

measures of ASD knowledge; (c) longitudinally assess potential

changes in PPCPs’ clinical practices following their participation

in educational/training opportunities; and (d) investigate the

acceptability of in-clinic supports (e.g., a best practice advisory),

in concert with educational opportunities, to remind providers

of appropriate courses of action at the point-of-care. Because the

response rate to participate in our webinar series was low, alternate

approaches to disseminating webinar content should also be explored

to provide more acceptable, on-the-go training opportunities that

providers can tailor to more precisely meet their educational needs.

Summary & Conclusion

Understanding PPCPs’ Knowledge of and Confidence in ASD

screening, diagnosis, and referral practices may allow behavioral health

professionals (e.g., psychologists, school-based personnel)

to collaborate more effectively with PPCPs by streamlining referral processes for ASD evaluation and facilitating earlier connections

with intervention services that ultimately stand to improve children’s

developmental outcomes. Our pilot findings highlight the promise of

a brief, webinar-based approach for improving PPCPs’ self-reported

ASD-care knowledge, as well as the need for more accessible, effective

educational tools and supports for PPCPs that will help close the

ASD-detection gap and provide immediate provisions for affected

children and their families.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by a gift from the William Stamps

Farish Foundation to Dr. Goin-Kochel. Research reported in this

publication was also supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver

National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the

National Institutes of Health under Award Number 1U54 HD083092

for partial support of Drs. Goin-Kochel’s and Ahmad’s effort. The

content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not

necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of

Health. We wish to thank all of the providers who participated in

this project; Dr. Stan Spinner for his assistance with the recruitment

efforts and overall support of our research program; and the team at

Diagnose First for building and refining the webinar platform, as well

as their permission to use videos from their extensive library.