Journal of Pediatrics & Child Care

Download PDF

Case Report

An Unintended Case-Control Study: Corticosteroid Growth Restriction in a Monozygotic Twin

Alexandr Magder EL and Jerry Zimmerman

1 Albany Medical Center, 363 Ontario St #C101, Albany, New York, USA,

2Seattle Children’s Hospital, New York, USA

2Seattle Children’s Hospital, New York, USA

*Address for Correspondence:Alexandr Magder EL, Albany Medical Center, 363 Ontario

St #C101, Albany, New York, USA, Tel: +1-518-772-8097, Email: magdera@amc.edu

Submission: 23 May 2023

Accepted: 15 June 2023

Published: 16 June 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Alexandr Magder EL, et al. This is an open

access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution

License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution,

and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work

is properly cited.

Keywords: Asthma; Growth/Developmental milestones; Inhaled corticosteroids

Abstract

Medication errors are an important cause of morbidity and

mortality in children, occurring roughly every 8 minutes for children

under 6. Among all medical errors, medication dosing errors are

very common. In this context, we present the case of amonozygotic

twin girl with severe, persistent asthma, who erroneously received

a double dose of nebulized budesonide (2 mg/day) for a period

of 23 months. Although the patient’s height and weight tracked

along the 50thpercentile before starting budesonide, these growth

measures fell to the 5th and 10thpercentile respectively following the

initiation of this prescription error, despite having improved asthma

control over this period. In contrast, during the same time period, the

patient’s twin sister experienced normal growth along the 50th centile.

Furthermore, this patient experienced long-term harm: three years

after discontinuing the erroneous budesonide dose, growth did not

return to the 50th percentile and a DEXA scan documented persistent

osteopenia, a known side effect of corticosteroids.

This case highlights key considerations to reduce harm using ICS medications: First, any changes in growth trajectory should prompt a review of inhaled corticosteroid medications being used. Second, corticosteroid medications should be reviewed at any hospital visit. The use of clinical standard work pathways in primary care and the emergency department can help to standardize medical management and reduce the risk of medical errors. Finally, minimal effective doses of corticosteroids (and all medications) should be prescribed.

This case highlights key considerations to reduce harm using ICS medications: First, any changes in growth trajectory should prompt a review of inhaled corticosteroid medications being used. Second, corticosteroid medications should be reviewed at any hospital visit. The use of clinical standard work pathways in primary care and the emergency department can help to standardize medical management and reduce the risk of medical errors. Finally, minimal effective doses of corticosteroids (and all medications) should be prescribed.

Abbreviations

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

(DEXA), Medication taken inhaled (INH), Medication taken as

needed (PRN), Metered dose inhaler (MDI), Actuation (ACT)

Introduction

It is estimated that in the United States, a medication error

occurs every 8 minutes for a child under 6 years of age [1]. Following

medication omission, the second most commonly cited medication

error is incorrect dosage [2]. Here we present the case of a prepubertal

girl who received an unintended double dose of nebulized

corticosteroid for 23 months and experienced substantial growth

restriction as compared to her monozygotic twin.

While inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are recommended as firstline

therapy for the control of asthma and have a clear benefit in

reducing related morbidity and mortality, [3] chronic ICS use has

the potential to reduce growth velocity [4-6]. While ICS doses above

100 mcg offluticas one or equivalent result in minor improvements

to asthma control, adverse impact on growth restriction is dose-dependent,

with minimal effects at therapeutic doses [4].

This case report ascertains the need for regular medication review and robust practices to monitor both benefit as well as potential risks of long-term corticosteroids administered to pre-pubertal children.

Case Presentation

This is the case of a monozygotic twin girl, born at 34weeks, 4

days estimated gestational age, who was evaluated at the age of 3.5

years for severe, uncontrolled asthma in a respiratory clinic at a

Canadian tertiary pediatric centre. The referral had been requested

one-month prior by an emergency department physician following a

severe asthma exacerbation in this toddler. At the time of her initial

clinic assessment, the patient’s parents reported a series of episodes

consisting of acute-onset shortness of breath in the absence of viral

symptoms or identified environmental triggers, which responded

to nebulized salbutamol. Despite a 1-month tapered course of oral

prednisolone, initially 2mg/kg/day, the parents reported that the

patient required a rescue dose of inhaled salbutamol every four

hours to control her symptoms. At this time the patient’s regular

medications included salbutamol metered-dose inhaler (MDI) as

required, vitamin D6000 IU by mouth once daily, montelukast 4mg

by mouth at bedtime, and mometasone nasal spray 50mcg once daily.

The therapeutic outcome of this visit was addition of a fluticasone/

salmeterol 25/125 mcg/actuation (ACT) MDI dosed twice daily.

A complicating factor in the control of this patient’s asthma was

an underlying diagnosis of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) deficiency.

This condition was diagnosed after a referral to immunology following

a series of lower respiratory tract infections and recurrent otitis media

requiring antibiotic treatment from the age of two years.

In comparison, the patient’s monozygotic twin sister had two

presentations to the emergency department for laryngotracheo

bronchitis between 2 -3 years of age, she did not have a history of

recurrent infections, persistent asthma symptoms, and was never

diagnosed with MBL deficiency. The parents did however report

the twin sister was referred to pulmonology for recurrent symptoms

consistent with reactive airway disease (RAD) and was prescribed inhaled fluticasone 50 mcg (roughly equivalent to 95 mcg budesonide) [7], dosed once daily to be taken with exacerbations. This medication

was used infrequently (fewer than 30 days over the year) and was

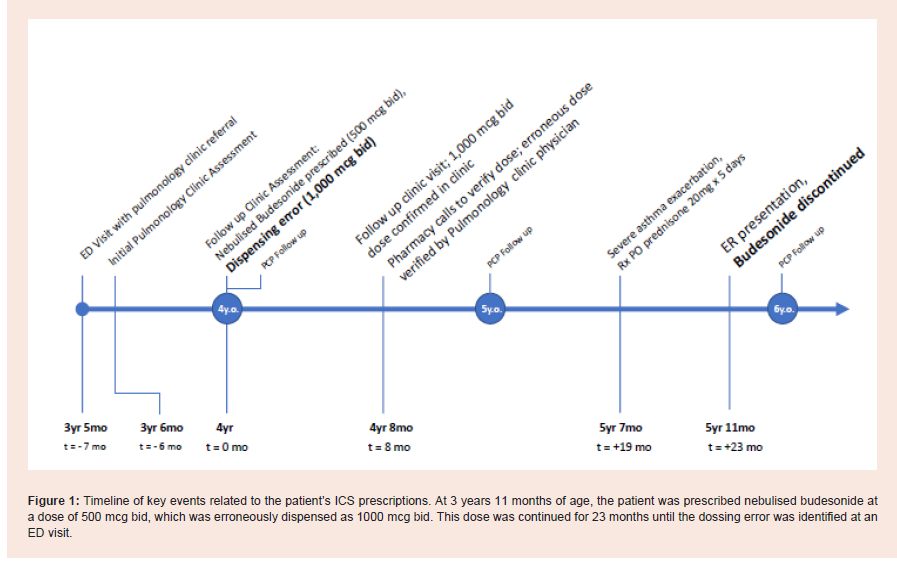

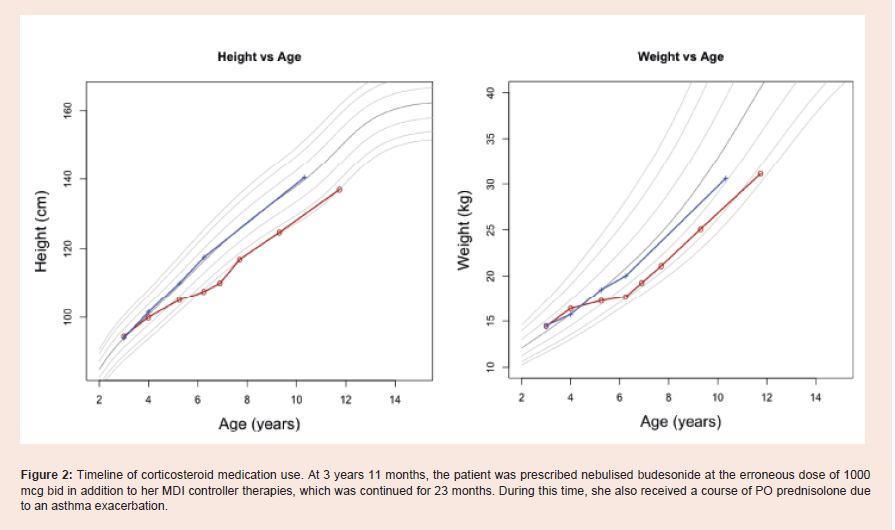

discontinued after 6 months [Figure 1 and 2 ].

Between clinic visits, which occurred annually with the patient’s

pediatrician and roughly every 6 months with the pediatric

pulmonology clinic, the patient continued to experience asthma

exacerbations, with roughly one ED visit per month, one of which was

severe enough to warrant a one-week prescription of PO prednisone

dosed 2mg/kg/day.

At the first follow-up visit following this enteral course of

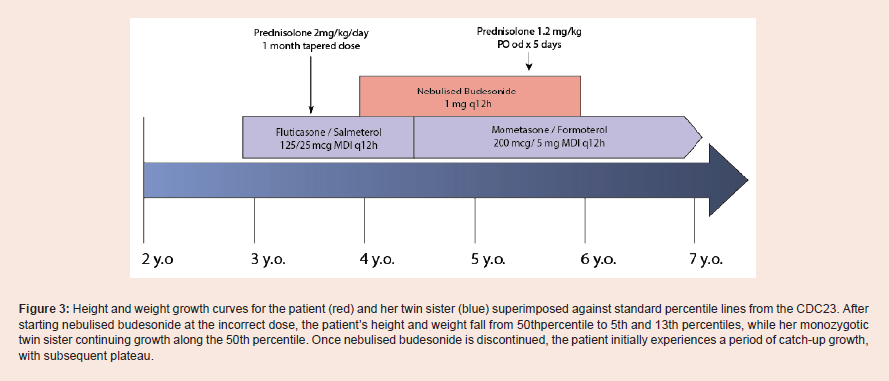

prednisone, the patient’s height and weight tracked along the 50th

percentile. At this time her medications included fluticasone/

salmeterol 125/25mcg/ACTMDI two inhalations twice daily, lansoprazole

15mg by mouth once daily, nebulised ipratropium bromide

every 6 hours as needed, and salbutamol MDI 100 mcg every 4 hours

as needed taken once a day when well.

Due to the recurrent nature of her asthma exacerbations, a

decision was made to start nebulized budesonide at a dose of dosed

500 mcg twice daily when the patient was 3 years 11 months old.

However, the pharmacy erroneously dispensed nebulised budesonide

at a dose of 1000 mcg twice daily, double the highest budesonide

dose recommended by the FDA [8]. After 8 months, the pharmacy

noticed the error and contacted the prescribing physician. Despite a

correction from the prescribing physician, the pharmacy continued

to dispensetheerroneous higher dose of 1000 mcg twice daily.

Budesonide 2000 mcg daily was continued for a period of 23 months from 4 to 6 years of age. During this time, the patient remained on

fluticasone/salmeterol 125/25mcg MDI twice daily until 4 years 8

months of age, when this was exchanged in favor of mometasone/

formoterol 200mcg/5mg/ACT twice per day. During this time, she

experienced improved asthma symptom control per parental report,

with a single substantial exacerbation at 4 years 6 months that

required a 5th day course of oral prednisolone, dosed 1.2mg/kg/day.

from 4 to 6 years of age. During this time, the patient remained on

fluticasone/salmeterol 125/25mcg MDI twice daily until 4 years 8

months of age, when this was exchanged in favor of mometasone/

formoterol 200mcg/5mg/ACT twice per day. During this time, she

experienced improved asthma symptom control per parental report,

with a single substantial exacerbation at 4 years 6 months that

required a 5th day course of oral prednisolone, dosed 1.2mg/kg/day.

At the age of 6 years 0 months, 23 months after starting nebulised

budesonide at the erroneous dose, the patient presented to the

emergency department following a one-day history of lethargy,

vomiting, loss of balance, frontal headache, and poor oral intake,

identified as concerning for adrenal failure per the emergency

department discharge summary. A review of the patient’s medications

was performed at that time, which revealed the underlying prescription

error. On discharge, the nebulised budesonide discontinued entirely.

Within one month of the cessation of the inhaled budesonide,

a growth chart assessment indicated that the patient’s height and

weight tracked at the 5th and 10th centiles respectively. In contrast, on

this date, the patient’s identical twin tracked at the 50th percentile for

both height and weight. A DEXA scan of the patient revealed bone

mineral density loss in the lumbar spine, corresponding to an agematched

Z-score of -2.5.

Three years after discontinuing budesonide, the patient was

diagnosed with steroid-induced osteoporosis with at Z-score of -1.7.

At this time, her height and weight corresponded to the 5th and 13th

centiles respectively. In contrast, her twin sister continued to track

along the 50th centiles for height and weight. Between the age of 4-5, while receiving 2000 mcg of budesonide daily, the patient experienced eight asthma exacerbations resulting in emergency department visits.

However, between the ages of 5-11 years, the patient experienced at

most 1 exacerbation per year, while undergoing accelerating growth

velocity [Figure 3].

Figure 1: Timeline of key events related to the patient’s ICS prescriptions. At 3 years 11 months of age, the patient was prescribed nebulised budesonide at a dose of 500 mcg bid, which was erroneously dispensed as 1000 mcg bid. This dose was continued for 23 months until the dossing error was identified at an

ED visit.

Figure 2: Timeline of corticosteroid medication use. At 3 years 11 months, the patient was prescribed nebulised budesonide at the erroneous dose of 1000 mcg bid in addition to her MDI controller therapies, which was continued for 23 months. During this time, she also received a course of PO prednisolone due to an asthma exacerbation.

Figure 3: Height and weight growth curves for the patient (red) and her twin sister (blue) superimposed against standard percentile lines from the CDC23. After starting nebulised budesonide at the incorrect dose, the patient’s height and weight fall from 50thpercentile to 5th and 13th percentiles, while her monozygotic twin sister continuing growth along the 50th percentile. Once nebulised budesonide is discontinued, the patient initially experiences a period of catch-up growth,

with subsequent plateau.

Discussion

Several factors implicate the patient’s corticosteroid prescription

in her growth restriction noted between 4-6 years of age. Most

importantly, the patient’s growth velocity notably increased once

the incorrect budesonide prescription was discontinued. In addition,

osteopenia noted in the lumbar spine is a typical adverse effect of longterm

corticosteroid use [9-11]. However, lansoprazole, prescribed in

the setting of high dose corticosteroid administration, may have also

contributed to the osteopenia [12]. Finally, the substantial difference

in the growth curves of the two girls, with the patient falling to the

5th and 13th percentiles for height and weight, while her monozygotic

twin sister continuing growth along the 50th centiles, provides a strong argument that differences in inhaled corticosteroid dosing

played a major role[Figure 3]. While the patient was administered

2000 mcg inhaled budesonide and 400 mcg fluticasone (equivalent

to 900 mcg budesonide) [7] per day, her twin sister received 50 μg of

inhaled fluticasone (equivalent to 95 mcg budesonide) [7] per day for

fewer than 30 days annually.

The most compelling alternative reason for the patient’s growth

restriction is the patient’s poorly controlled asthma. The patient’s

MBL deficiency should be considered in this context, as it has been

postulated this condition may contribute to airway inflammation and

thus increase the risk of developing asthma [13]. However, the patient

experienced poorly controlled asthma for two years before the start of

the budesonide prescription at the erroneous dose, during which time

the patient’s growth velocity closely followed that of her sister and

remained along the 50th percentile. In addition, rather than growth

velocity increasing following improved symptomatology between 5-6

years of age, the patient continued to experience lower than expected

growth velocity, falling from the 50th centile to the 5th centile for

height.

While data remains conflicting regarding the effects of ICS

medications on linear growth at regular dosing, a 2014 Cochrane

review suggested low or medium-dose ICS use was associated with

a reduction in linear growth velocity of 0.48 cm/year, particularly in

the first year of ICS therapy [14]. In addition, it should be noted some

studies have reported a decrease in final adult height in the range of

1.2cm on average, even at moderate ICS dosing [15].Effects on growth

have been reported to be dose dependent, and are most significant

above a dose of 0.4mg/day, a threshold far surpassed by this patient

over a period of two years [15]. By age 6, the patient’s height was

nearly 10cm less than her twin sister, which further widened to 15cm

at 10 years of age, suggesting a long-lasting difference in final adult

height is likely.

This case highlights the importance of regular review of

medications and assessment of growth for children with asthma,

particularly those prescribed corticosteroids [16]. In many cases,

inhaled corticosteroid dose responses plateau at 200 mcg fluticasone

per day or equivalent, and few children benefit from dose increases

beyond 500 mcg day [17] (equivalent to 1000 mcg budesonide) [7].

Thus, dosing beyond this threshold was unlikely to provide additional

symptom control, which explains why the patient continued to

experience severe asthma exacerbations.

From a systems perspective, there are a number of key drivers

that contributed to this medication error: 1) faltering growth should

have raised concern with the patient’s pediatrician; 2) at the time of

the error, the pulmonology clinic used paper charts which did not

display warnings for doses; 3) the pharmacy should have verified

the dose immediately, rather than 8 months later; and finally, 4) the

improvement in the patient’s asthma control should have prompted a

review of her corticosteroid medications.

Implementation of asthma clinical standard work pathways

represent potential solutions to increase adherence to NIH asthma

guidelines [18]: the “Primary Care Pathway for Childhood Asthma”

[19] is an example currently being studied for primary care, and

many children’s hospitals employ clinical pathways to standardize

asthma care in their emergency department and following hospital

discharge [20]. In hospital, mandatory reconciliation of admission/

discharge medications can identify errors or concerns [21]. These

medication safety exercises and standardized treatment algorithms

may have been particularly useful for this patient and may have

prevented harm.

In summary, while inhaled corticosteroids remain the most

effective therapy available for maintenance treatment of childhood

asthma, it is imperative that clinicians use the lowest-effective

corticosteroid dose for treating asthma (or other corticosteroidresponsive

conditions). Importantly, growth charts should be regularly

reviewed in the context of chronic corticosteroid administration, and

a full medication review should occur if growth begins to falter [22].

Contributors’ Statement Page:

Dr Magder obtained the consent from the patient’s family for

publishing, created the figures, and drafted the initial manuscript.Dr Zimmerman supported the drafting of the initial manuscript

by providing expert advice on the interpretation of clinical data,

supported the creation of the figures and revised the initial manuscript

for accuracy.

Dr Magder and Dr Zimmerman critically reviewed and edited the

revised manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate:

Approval granted by the Royal College of Surgeons Research

Ethics Board.Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the family for giving us the privilege to

learn from this case study. We understand how difficult this period in

their lives has been, and we hope this case will help prevent similar

errors in the future.