Journal of Pediatrics & Child Care

Download PDF

Case Report

Animal-Assisted Interventions in Paediatric Oncology: The Story of Francesco and His Friend Megan

Chiara Rutigliano MA1*, Jessica Forte2, Teodoro Semeraro3, Alessandra Creti3, Rosa Maria Daniele2 and Nicola Santoro2

1Psychologist, Section of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology,

University Hospital of Bari,APLETI ETS, p.zza Giulio Cesare 11,

70124, Bari, Italy

2Section of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology, University Hospital of Bari, p.zza Giulio Cesare 11, 70124, Bari, Italy

3AAT, Vir LABOR AAI Center, Carovigno, Brindisi, Italy

2Section of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology, University Hospital of Bari, p.zza Giulio Cesare 11, 70124, Bari, Italy

3AAT, Vir LABOR AAI Center, Carovigno, Brindisi, Italy

*Address for Correspondence: Chiara Rutigliano MA, Psychologist, Section of Pediatric Hemathology-Oncology, University Hospital of Bari, p.zza Giulio Cesare 11, 70124, Bari, Italy

Email: rutigliano.chiara@gmail.com

Submission: 29 June 2023

Accepted: 31 July 2023

Published: 03 August 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Chiara Rutigliano MA, et al. This is an open

access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution

License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution,

and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work

is properly cited.

Abstract

Children affected by neoplasia face extended periods

of hospitalisation and lengthy, invasive courses of treatment.

Complementary non-pharmacological therapies, as Animal-Assisted

Interventions (AAI), are more frequently being used and integrated

alongside traditional forms of treatment with the objective of easing

adaptation to the hospital environment.

AAI is an umbrella term that includes animal-assisted activities (AAA), animal-assisted therapy (AAT), and animal-assisted education (AAE) and AAI Resident animals (RA)

Animal-Assisted Interventions (AAI) allow for the creation of meaningful relationships between people and animals: AAI’s aims are therapeutic, educational, and social, and are designed to increase a person’s sense of wellbeing.

This case-report presents the story of Francesco, a boy of 9 with leukaemia, and his sessions with Megan, a 10-year-old Labrador Retriever. The ways in which AAI has allowed Francesco to counter boredom, fear, pain, and anxiety related to hospitalization are illustrated.

AAI is an umbrella term that includes animal-assisted activities (AAA), animal-assisted therapy (AAT), and animal-assisted education (AAE) and AAI Resident animals (RA)

Animal-Assisted Interventions (AAI) allow for the creation of meaningful relationships between people and animals: AAI’s aims are therapeutic, educational, and social, and are designed to increase a person’s sense of wellbeing.

This case-report presents the story of Francesco, a boy of 9 with leukaemia, and his sessions with Megan, a 10-year-old Labrador Retriever. The ways in which AAI has allowed Francesco to counter boredom, fear, pain, and anxiety related to hospitalization are illustrated.

Introduction

Children affected by neoplasia face extended periods of

hospitalisation and lengthy, invasive courses of treatment. This also

brings difficulties in adjusting to the hospital environment, and

psychophysical stress [1]. The literature reports that children with

oncological conditions show an increased dependence on parental

figures, regression to earlier phases of development, aggression,

and increased levels of fear, sleep disorders, and eating disorders

[2] a. Complementary non-pharmacological therapies are more

frequently being used and integrated alongside traditional forms of

treatment [3,2] with the objective of easing adaptation to the hospital

environment [4] reducing anxiety levels about medical procedures

[5,6] and establishing relationships that can positively impact the

psychophysical wellbeing of young patients.

Animal-Assisted Interventions (AAI) allow for the creation of

meaningful relationships between people and animals: AAI’s aims are

therapeutic, educational, and social. Designed to increase a person’s

sense of wellbeing, this type of intervention is increasingly used in

paediatric oncology [7,8]. The literature describes how the presence

of animals in a hospital setting can be a distraction, source of pleasure,

and therapy for children [9] improving their mood and counteracting

the boredom, fear, pain and anxiety connected to hospitalisation [10].

Although there is some literature regarding the efficacy of AAI.

This article presents the story of Francesco, a boy of 9 with

leukaemia, and his sessions with Megan, a 10-year-old Labrador

Retriever. The theoretical framework for this intervention was

based on the “Linee Guida Nazionali per gli interventi assistiti

con gli animali (IAA)” [National Guidelines for Animal-Assisted

Interventions (AAI)], approved at the Italian State-Regional

Conference in March 2015 [11] with an approach centred around the

empathetic relationship between human and animal.

Pet Care:

The project “PET CARE – Animal-Assisted Interventions (AAI)”

has been running since 2018 in the Paediatric Oncohaematology unit

of the Policlinico Hospital in Bari, for inpatients and outpatients

aged between 18 months and 19 years of age who are undergoing

chemotherapy. The staff consists of the project coordinator (the

Medical Director of Paediatric Oncology), a veterinary behaviourist,

two assistant dog handlers with experience in behaviourism, and an

intervention coordinator (the unit’s psychotherapist) trained and

certified in AAI, as well as four dogs: two Labrador Retrievers of

around four years of age, another Labrador Retriever aged ten, and

a French Bulldog aged four and a half. The dogs are all certified that

their behavioural responses are appropriate to the stimuli present in

the setting: in addition, they have been trained to perform specific

activities in AAI sessions, so that they can take on the role of stimulator

within the therapeutic relationship. In accordance with a protocol

formulated jointly by oncologists and veterinarians, the project

requires a specific prophylaxis for the dogs, to prevent infection and

potential health risks for immunocompromised patients. To date, no

suspected cases of zoonosis have been recorded.The following two parameters are used to identify patients who

could participate in AAI:

A: medical criteria, assessing the clinical condition of the child.

B: psychological criteria, evaluating the relevance of the activity

and the possibility of carrying out individual, personalised sessions;

the child’s particular needs; their own unique personal history; their

current state of health; how well they are adapting to, and coping

with, treatment; and the consequent psycho-emotional ramifications

that every patient has to deal with.

PET CARE is integrated within a multidisciplinary,

interdisciplinary team that is responsible for the treatment of all

patients in the Paediatric Oncohaematology unit.

The patients’ parents are an integral part of the process and are

often directly involved in the sessions.

There are 12 hours of PET CARE sessions each week. The sessions

take place either in a designated area which has been set aside for

the project, in accordance with the hospital’s safety and privacy

standards, or in patients’ rooms, but only after receiving clearance

from medical staff.

Francesco:

Francesco is nine years old, the third child in a family with two

older sistersand has been diagnosed with T-cell acute lymphoblastic

leukaemia. His treatment follows the AIEOP - BFM ALL 2017

protocol: it is a lengthy and complex process, and Francesco is

regularly subject to invasive medical procedures (lumbar punctures,

bone marrow aspiration). In addition, his treatment also entails

different medication at different times, with a resultant accumulation

of side effects.High doses of cortisone can lead to changes in mood and mood

swings, aggression and depression, as well as increased appetite

and obsessive thoughts about food, causing weight gain and fluid

retention [12]

Vincristine can cause peripheral neuropathy and lower limb

asthenia, making walking difficult. [13]

For these reasons, it has been difficult for Francesco to adapt to

the hospital environment, and he has a lot of questions for his doctors.

During his first admissions to hospital, he displayed both anger and

frustration. In general, he seems to express his emotions, but often,

due to the emotional burden of his situation, struggles when talking

about them in greater depth. He has found it hard to leave his room

and interact with the other children.

Weight gain and the progressive thinning of his hair have made

noticeable changes to Francesco’s appearance, making him “different”

to other children.

One consequence of Francesco’s course of chemotherapy is a

weakened immune system, and a greater susceptibility to infection.

In turn, this means that when he goes home, he has to limit social

contact, further isolating him from his friends and his wider family.

During a session with the psychologist, Francesco mentioned

that he is an animal lover. However, he had never had a pet, as his

parents were against the idea of having animals in the house. After a

consultation with the team, AAI was proposed for Francesco.

Francesco and Megan:

Francesco’s first AAI session with Megan (a ten-year-old Labrador) and the specialist AAI practitioners took place in January 2021. During this initial session, Francesco was agitated and irascible,

approaching Megan with sudden, abrupt movements. As a result, the

practitioners decided to focus the activities on relationship-building

and caring for the dog, in order to induce Francesco to adjust and

calm his behaviour. He quickly adapted to Megan’s needs, paying

attention to how his approach was perceived by the animal, her

responses, and the emotional state that resulted from the activities

which he implemented. This was immediately reinforced by the

positive emotions displayed by Megan during the session.After two observation sessions, an individual program of 24 AAI

sessions was proposed for Francesco, with the following objectives:

1. Working to counteract the side effects of the cortisone, such as

excessive aggression or depression;

2. Combatting the demotivation deriving from the effects of

muscular fatigue, a side effect of vincristine;

3. Contributing to a reduction in anxiety and worry;

4. Improving Francesco’s experience in hospital, and coping

strategies.

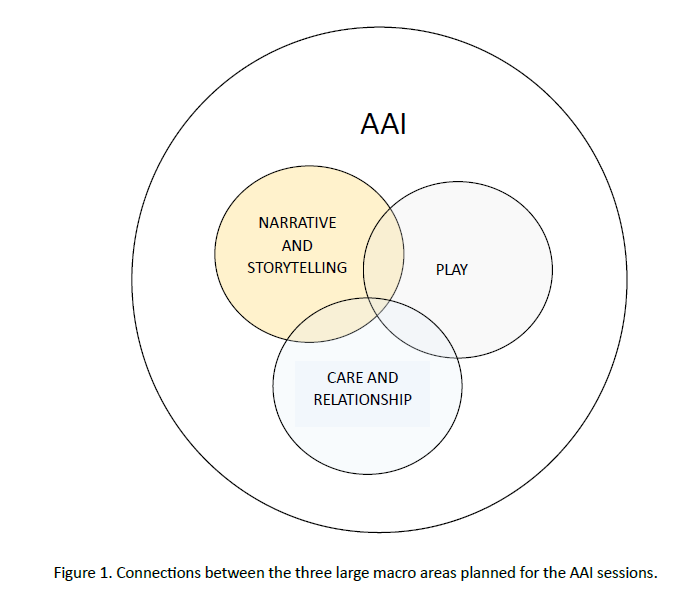

The activities planned for the sessions related to three large macro

areas [Figure 1]:

1. Care and relationship-building;

2. Narrative and storytelling activities;

3. Play.

The activities in these three areas were connected and could also take place at the same time during a session. They were planned and delivered in accordance with the psychophysical state of the child. The team prepared a general plan for each session, which could then be adapted to suit the moment or, as the weeks went by, to include Francesco’s own suggestions.

1. Care and relationship-building;

2. Narrative and storytelling activities;

3. Play.

The activities in these three areas were connected and could also take place at the same time during a session. They were planned and delivered in accordance with the psychophysical state of the child. The team prepared a general plan for each session, which could then be adapted to suit the moment or, as the weeks went by, to include Francesco’s own suggestions.

Care and relationship-building:

Taking care of Megan through activities like stroking her, brushingher coat, feeding her, and listening to her heart with a stethoscope

(an instrument used every day by the doctors during their rounds),

allowed Francesco to create an affective dimension of exchange

and trust between himself and Megan. Thanks to these activities,

Francesco was able to experience a sense of gratification, becoming

less closed off and less worried about his current circumstances.

This reinforced his self-confidence, allowing him to build his coping

mechanisms when dealing with medical staff and with his treatment,

dispelling some of his fears about doctors’ visits and, in particular,

invasive procedures. Francesco’s mother noted that using the

stethoscope to listen to Megan’s heart calmed him down and made

him less aggressive.

Narrative and storytelling activities:

From the start, Francesco showed a keen interest in dogs,

especially in their behavioural characteristics and how to look after

them. This was the first topic that Francesco wanted to explore,

so it seemed useful to focus the first part of the work on this area.

Talking about their traits, potential difficulties with socialisation,

and the particular needs of different breeds allowed Francesco to

draw parallels with the difficulties that he was experiencing at that

time and identify his own needs. Furthermore, Francesco was able to

pick out a number of topics that he was interested in learning more

about he would bring these up at the end of a session, with the aim

of discussing them in more depth the following week. This ensured a

sense of continuity and structure over the course of the sessions.

These activities allowed Francesco to slowly open up and talk

about himself.Play:

The sessions included a moment of interactive physical activity

between Francesco and Megan. The objective was to create moments

of pure play and fun, through activities such as “find work”, throwing

a ball and simple obstacle courses. These activities were beneficial in

counteracting the side effects of Francesco’s treatment. For example,

his difficulties with walking that resulted from chemotherapeutical

such as vincristine were compensated by interactions with the dog in

games such as “fetch”. Furthermore, in these games Francesco was

motivated by the interaction and by having fun, which made him

more inclined to overcome, or take more care to manage, his physical

limitations. In the time between one session and the next, Francesco

planned games to play with Megan, which were then used in the

following session, thanks to the assistance of the AAI practitioners.Discussion

AAI helped Francesco to radically alter his approach to

hospitalisation. He waited for the dog’s arrival, was brought to the

hospital specially to see Megan, and asked the doctors to schedule his

appointments to coincide with days when AAI sessions were taking

place [Figure 2].

He was able to build trusting relationships within the hospital

setting and with the medical staff, especially with the doctors and the

practitioners who worked with him during AAI. Megan became a

point of contact and of engagement with the hospital, providing an

opening towards a greater sense of serenity, from which to observe

and undergo his ongoing course of treatment.

Over time, Francesco created meaningful relationships with the

team responsible for his care. He actively worked with them during

routine procedures, steadily increasing in his adherence to protocols

and treatment, thus reinforcing trust and affection.At the same way,

as reported by one member of the team, AAI positively affected their

work: “AAI has a positive impact on our work as doctors, because it

prepares children to accept therapies more easily, making the hospital

environment more serene, improves the perception that patients have

of the periods of hospitalization.

Furthermore, AAI is also a moment of well-being for us operators.

We are often directly involved in the activity, and this allows us to

create a different feeling with the child, a greater compliance beyond

the strictly medical role. Living in a more serene environment also

predisposes us to work in a more positive way. Observing the child

during AAI provides us with further tools for understanding that

patient, helping to improve his management “.

His trust towards the medical and paramedical staff was often

transmitted to other children in the unit, with whom Francesco

interacted.

Through his relationship with Megan, Francesco lowered his

emotional defences and restored his sense of tranquillity. He was able

to express his own emotions, creating a safe space within the stressful

environment of the hospital, and find strategies to tackle them and

process his experiences.

The continuity afforded by the AAI sessions guaranteed a

constant, secure emotional space for Francesco during his treatment,

as well as moments of fun and diversion: it created a bridge, to look

beyond his leukaemia. During his treatment, Francesco even started

to think about having a dog of his own in the future and made an

effort to find out more about dogs, how to train them, and how they

experience the world.

Furthermore, AAI also became important within the context of

Francesco’s family, who were very receptive and always present during

the sessions. In the words of his parents: “With regard to everything

that was happening to him, Francesco had an excellent approach to

the activity, despite the fact that he had never had the chance to have

a dog at home. The activities with the dog were a stimulus to react to

the consequences of our son’s treatment: notwithstanding his health

problems like weakness, problems with his joints, boredom, and

despondency, he managed to overcome these when he knew he had the

sessions with Megan: he was even excited to go to the hospital, when

he could do the activities with her. This also had a positive effect on

our family, because we then decided to get a dog, as a way to help us

through this tough time. We believe that AAI is, without a doubt, a

positive activity: we would go as far as to say that it is indispensable

for all people who find themselves facing such devastating situations,

because the world of animals changes your approach to disease and

helps you to see the world in a different way. The dog and the child need

each other… and this is the secret”.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank APLETI ETS for passion, love, and

care in supporting since 41 years old children with cancer and their

family hospitalized at Unit of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology in

AUOC Policlinic of Bari (Italy).