Journal of Pharmaceutics & Pharmacology

Targeting the Endocannabinoid System for Neuroprotection: A 19F-NMR Study of a Selective FAAH Inhibitor Binding with an Anandamide Carrier Protein, HSA

Jianqin Zhuang1,2, De-Ping Yang3, Xiaoyu Tian1, Spyros P. Nikas1, Rishi Sharma1, Jason Jianxin Guo1*and Alexandros Makriyannis1*

- 1Center for Drug Discovery, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, and Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Northeastern University, 360 Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA

- 2Department of Chemistry, The College of Staten Island, City University of New York, 2800 Victory Boulevard, Staten Island, NY 10314, USA

- 3Physics Department, College of the Holy Cross, 1 College Street, Worcester, MA 01610, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Jason Jianxin Guo and Alexandros Makriyannis, Center for Drug Discovery, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, and Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Northeastern University, 360 Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA, Phone: 617-373-4219, 617- 373-4200; E-mails: j.guo@neu.edu, a.makriyannis@neu.edu

Citation: Jianqin Zhuang, De-Ping Yang, Xiaoyu Tian, Spyros P. Nikas, Rishi Sharma, et al. (2013) Targeting the Endocannabinoid System for Neuroprotection: A 19F-NMR Study of a Selective FAAH Inhibitor Binding with an Anandamide Carrier Protein, HSA. J Pharmaceutics Pharmacol 1: 002.

Copyright © 2013 Zhuang J, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Pharmaceutics & Pharmacology | ISSN: 2327-204X | Volume: 1, Issue: 1

Abstract

Fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), the enzyme involved in the inactivation of the endocannabinoid anandamide (AEA), is being considered as a therapeutic target for analgesia and neuroprotection. We have developed a brain permeable FAAH inhibitor, AM5206, which has served as a valuable pharmacological tool to explore neuroprotective effects of this class of compounds. In the present work, we characterized the interactions of AM5206 with a representative AEA carrier protein, human serum albumin (HSA), using 19F nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Our data showed that as a drug carrier, albumin can significantly enhance the solubility of AM5206 in aqueous environment. Through a series of titration and competitive binding experiments, we also identified that AM5206 primarily binds to two distinct sites within HSA. Our results may provide insight into the mechanism of HSA-AM5206 interactions. The findings should also help in the development of suitable formulations of the lipophilic AM5206 and its congeners for their effective delivery to specific target sites in the brain.Introduction

The endocannabinoid system has been implicated as a therapeutic target for analgesia, anti-emesis, and neuroprotection [1-3]. The blockade of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) can lead to a chronic elevation of the endocannabinoid anandamide (AEA) levels at the synapse [4,5]. Importantly, this produces few undesirable side effects typically associated with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the active psychotropic ingredient in marijuana [6]. For this reason, selective FAAH inhibition offers an attractive strategy to obtain the beneficial effects of CB1 receptor activation. Recently, it was reported that the cellular uptake of AEA can be significantly potentiated by a class of anandamide carrier proteins such as albumin and fatty acid binding proteins (FABPs) [7,8]. By inhibiting these anandamide carrier proteins, the uptake of AEA inside the cell was found to be drastically reduced. These findings provide a potential new therapeutic modality for neuroprotection through dual inhibition of FAAH and anandamide carrier proteins.Serum albumin has long been regarded as a carrier protein for various lipophilic endogenous and exogenous compounds to their specific targets [15,16]. As a drug carrier, albumin is a highly helical protein containing three homologous domains (I, II, and III), each consisting of two subdomains (A and B) [17-19]. Two structurally selective drug-binding sites, which are located in subdomains IIA and IIIA, are primarily associated with the delivery of various drug molecules [20-22]. A number of biophysical techniques have been used to study the interactions of ligands with albumin. These include fluorescence spectroscopy [23,24], gel chromatography [25], high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [26], electrospray ionization mass spectrometry [27] and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Although fluorinated natural products are relatively rare, it was reported that approximately 25% of drug molecules contain at least one fluorine atom [28]. For fluorine containing ligands, 19F-NMR has been of particular interest due to the fact that 19F has 100% natural abundance and 19F-signals are much more sensitive to changes in their chemical environment [29]. Additionally, because of the absence of fluorine atoms on proteins, the 19F-NMR spectra from mixtures of fluorinated ligands and their target proteins are much simplified.

Material and Methods

MaterialsResults and Discussion

Site selective binding characteristics of AM5206

To further explore the binding characteristics of AM5206 with human serum albumin, we performed a series of titration experiments by adding AM5206 to 0.6 mM HSA solution. Figure 3 shows the 19F-NMR spectra with various HSA to AM5206 ratios. At HSA: AM5206 molar ratios of 1:0.25 and 1:0.5, only one single peak at -83.86 ppm was observed. This shows that the fatty acid sites (FA sites) on albumin are easily accessible by AM5206 at low concentrations. At a ratio of 1:1, a peak at -86.77 ppm started appearing. With further additions of AM5206, the resonances at -85.44 and -87.95 ppm also started to appear. At a HSA: AM5206 ratio of 1:5, the signal at -85.44 ppm is ~10× stronger than all other peaks, thus providing additional evidence that this -85.44 ppm peak is due to non-specific binding of AM5206 to HSA. In our earlier study of AM5206 with BSA, the 19F signal from AM5206 at drug site 1 and non-specific site coalesce due to fast exchange. Conversely, in our HSA experiments, the -86.77 ppm (drug site 1) and -85.44 ppm (non-specific binding) peaks remained separate over the entire course of our titration experiments, suggesting a tight binding of AM5206 to HSA compared to BSA [14]. Additionally, at all HSA:AM5206 ratios, no peak was observed at -86.18 ppm due to free AM5206 in solution, suggesting a fast exchange with the nonspecific binding sites. Parallel NMR titration experiments were also conducted by adding the same amounts of AM5206 to HEPES buffer solution only. As shown in Figure 3, there was only one single sharp peak at -86.18 ppm due to free AM5206 in solution. The intensity of this peak remains virtually unchanged as the added amount of AM5206 stock increases from 1.5μL to 30 μL. No additional peak was observed due to any undissolved AM5206.

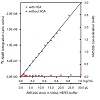

It is interesting to compare the integrations of the 19F-NMR spectra from these two parallel titration experiments. Since NMR detects only the “soluble” fraction of AM5206 in all sample preparations, it presents a unique methodology to quantify its solubility [33-35]. To ensure accurate integration, we first measured the integrals of different 19F-NMR spectra recorded using a range of recycle delays from 1 s to 30 s and confirmed that a 2 s recycle delay between scans is adequate. In Figure 4, we plotted the total integral values against the amount of AM5206 added in each NMR sample. When titrated into the HSA solution, the integral values increased linearly with the addition of AM5206. The black line represents the best-fit of the data points according to the linear regression model, and the r2 is found to be 0.993. Our data show that albumin can completely solubilize AM5206 up to 1.0 mg/ml concentration (30 μl AM5206 stock in 500 μl HSA solution). This corresponds to a 3.0 mM of AM5206 concentration in the HSA solution. In contrast, when AM5206 was added into HEPES buffer, the signal integral increased at the very beginning and leveled off for the remaining titration experiments. This corresponds to an AM5206 concentration of ~70 μM in the HEPES buffer solution. Therefore, albumin can significantly enhance the solubility of AM5206 in aqueous buffer solutions from ~70 μM to 3.0 mM, an approximately 50-fold increase.

Figure 4: Integration of 19F-NMR signals from AM5206 in HEPES buffer with HSA (blue squares) and without HSA (red circles). The two horizontal axes represent the actual amount of AM5206 stock solution (50 mM in DMSO) added and the corresponding amount of AM5206 in the NMR sample (mg/mL). The vertical axis on the right shows the concentration of the soluble portion of AM5206.

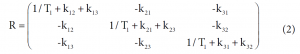

Among these three diagonal peaks, we found that with the increase of tm, the -85.44 ppm (peak #2) exhibited a much faster decay than the other two diagonal peaks; consistent with our assignment that this peak represents the non-specific binding of AM5206. As for the cross peaks, we found that the 1-3 and 3-1 pair, which is due to exchange between fatty acid sites and drug site 1, has a much smaller initial slope than all the other cross-peaks. This observation clearly indicated that the exchange between these two specific binding sites is much slower than exchanges involving the non-specific sites. Our calculated exchange rate constants showed that k13 is indeed almost two orders of magnitude smaller than either k21 or k23.

Conclusions

The interactions between a selective FAAH inhibitor AM5206 and human serum albumin have been studied using 19F NMR technique. The primary binding sites for AM5206 are drug site 1 located at subdomain IIA as well as fatty acid site(s) at subdomain IB and domain III. With excess amount of AM5206 added, it tends to associate with many of the non-specific binding sites on albumin. This drastically increases the aqueous solubility of AM5206. To further understand the binding events, we have also determined the exchange rates of AM5206 among various binding sites on HSA. Comparing to our earlier results with BSA, AM5206 has a much tighter binding to drug site 1 on human serum albumin. It has been demonstrated that the endocannabinoid anandamide also binds to HSA. It can thus be argued that AM5206 may compete with anandamide for HSA binding. The result of such a potential competition would be the enhancement of free anandamide levels. We conclude that in addition to its role as a FAAH inhibitor, AM5206 may further enhance its effects through the release of anandamide from HSA. We are now in the process of identifying the specific sites for anandamide binding with HSA. Further experiments are also underway to examine whether AM5206 can compete effectively with anandamide for binding with albumin.Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants DA003801 (A.M.), DA007215 (A.M.), DA007312 (A.M.), and DA032020 (J.G.) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.References

- Fowler CJ (2008) “The tools of the trade”--an overview of the pharmacology of the endocannabinoid system. Curr Pharm Des 14: 2254-2265.

- Piomelli D (2003) The molecular logic of endocannabinoid signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci 4: 873-884.

- Zogopoulos P, Vasileiou I, Patsouris E, Theocharis S (2013) The neuroprotective role of endocannabinoids against chemical-induced injury and other adverse effects. J Appl Toxicol: JAT 33: 246-264.

- Lichtman AH, Blankman JL, Cravatt BF (2010) Endocannabinoid overload. Mol Pharmacol 78: 993-995.

- Cravatt BF, Giang DK, Mayfield SP, Boger DL, Lerner, RA, et al. (1996) Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fattyacid amides. Nature 384: 83-87.

- Ahn K, Johnson DS, Cravatt BF (2009) Fatty acid amide hydrolase as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of pain and CNS disorders. Expert opinion drug discov 4: 763-784.

- Kaczocha M, Glaser ST, Deutsch DG (2009) Identification of intracellular carriers for the endocannabinoid anandamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 6375-6380.

- Maccarrone M, Dainese E, Oddi S (2010) Intracellular trafficking of anandamide: new concepts for signaling. Trends Biochem Sci 35: 601-608.

- Makriyannis A, Nikas SP, Alapafuja SO, Shukla VG (2008) Fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitors. WO 2008: 013963A2.

- Bahr BA, Makriyannis A, Karanian DA (2010) Dual modulation of endocannabinoid transport and fatty-acid amide hydrolase for treatment of excitotoxicity, US 20100234379 A1.

- Karanian DA, Brown QB, Makriyannis A, Kosten TA, Bahr BA (2005) Dual modulation of endocannabinoid transport and fatty acid amide hydrolase protects against excitotoxicity. J Neurosci 25: 7813-7820.

- Karanian DA, Butler D, Makriyannis A, Bahr B (2006) A Reversible FAAH Inhibitor Exhibits Efficient Bioavailability While Enhancing Neuroprotective Endocannabinoid Responses. The FASEB Journal 20: A1132.

- Naidoo V, Nikas S, Karanian D, Hwang J, Zhao J, et al. (2011) A New Generation Fatty Acid Amide Hydrolase Inhibitor Protects AgainstKainate-Induced Excitotoxicity. J MolNeurosci 43: 493-502.

- Zhuang J, Yang DP, NikasSP, Zhao J, Guo J, et al. (2013) The Interaction of Fatty Acid Amide Hydrolase (FAAH) Inhibitors with an Anandamide Carrier Protein Using (19) F-NMR. AAPS J.

- Kratz F (2008) Albumin as a drug carrier: design of prodrugs, drug conjugates and nanoparticles. J control release: official journal of the Controlled Release Society 132: 171-183.

- Kratz F, Elsadek B (2012) Clinical impact of serum proteins on drug delivery. J control release 161: 429-445.

- Carter DC, Ho JX (1994) Structure of serum albumin. Adv Protein Chem 45: 153-203.

- Petitpas I, Grune T, Bhattacharya AA, Curry S (2001) Crystal structures of human serum albumin complexed with monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Mol Biol 314: 955-960.

- He XM, Carter DC (1992) Atomic structure and chemistry of human serum albumin. Nature 358: 209-215.

- Dockal M, Carter DC, Ruker F (1999) The three recombinant domains of human serum albumin. Structural characterization and ligand binding properties. J Biol Chem 274: 29303-29310.

- Jisha VS, Arun KT, Hariharan M, Ramaiah D (2006) Site-selective binding and dual mode recognition of serum albumin by a squaraine dye, J Am Chem Soc 128: 6024-6025.

- Ghuman J, Zunszain PA, Petitpas I, Bhattacharya AA, Otagiri M, et al. (2005) Structural basis of the drug-binding specificity of human serum albumin. J Mol Biol 353: 38-52.

- Richieri GV, Anel A, Kleinfeld AM (1993) Interactions of long-chain fatty acids and albumin: determination of free fatty acid levels using the fluorescent probe ADIFAB. Biochemistry 32: 7574-7580.

- Il’ichev YV, Perry JL, Ruker F, Dockal M, Simon JD (2002) Interaction of ochratoxin A with human serum albumin. Binding sites localized by competitive interactions with the native protein and its recombinant fragments. Chem Biol Interact 141: 275-293.

- Kuchimanchi KR, Ahmed MS, Johnston TP, Mitra AK (2001) Binding of cosalane--a novel highly lipophilic anti-HIV agent--to albumin and glycoprotein. J Pharm sci 90: 659-666.

- Hollosy F, Valko K, Hersey A, Nunhuck S, Keri G, et al. (2006) Estimation of volume of distribution in humans from high throughput HPLC-based measurements of human serum albumin binding and immobilized artificial membrane partitioning. J Med Chem 49: 6958-6971.

- Benkestock K, Edlund PO, Roeraade J (2005) Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry as a tool for determination of drug binding sites to human serum albumin by noncovalent interaction. Rapid communications in mass spectrometry : Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 19: 1637-1643.

- Purser S, Moore PR, Swallow S, Gouverneur V (2008) Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chemical Society reviews 37: 320-330.

- Kitamura K, Kume M, Yamamoto M, Takegami S, Kitade T (2004) 19F NMR spectroscopic study on the binding of triflupromazine to bovine and human serum albumins, J Pharm Biomed Anal 36: 411-414.

- McMenamy RH, Oncley JL (1958) The Specific Binding of l-Tryptophan to Serum Albumin J Biol Chem 233: 1436-1447.

- Simard JR, Zunszain PA, Hamilton JA, Curry S (2006) Location of High and Low Affinity Fatty Acid Binding Sites on Human Serum Albumin Revealed by NMR Drug-competition Analysis. J Mol Biol 361: 336-351.

- Bain AD (2003) Chemical exchange in NMR. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy 43: 63-103.

- Dalisay DS, Molinski TF (2009) NMR quantitation of natural products at the nanomole scale. J Natural Prod 72: 739-744.

- Lin M, Tesconi M, Tischler M (2009) Use of (1)H NMR to facilitate solubility measurement for drug discovery compounds. Int J Pharm 369: 47-52.

- Diaz D, Bernad Bernad MJ, Gracia-Mora J, Escobar Llanos CM (1999) Solubility, 1H-NMR, and molecular mechanics of mebendazole with different cyclodextrins. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 25: 111-115.

- Kesanli B, Charles S, Lam YF, Bott SG, Fettinger J, et al. (2000) Probing individual steps of dynamic exchange with P-31 EXSY NMR spectroscopy: Synthesis and characterization of the [E7PtH(PPh3)](2-) Zintl ion complexes [E = P, As]. J Am Chem Soc 122: 11101-11107.

- Perrin CL, Dwyer TJ (1990) Application of 2-Dimensional Nmr to Kinetics of Chemical-Exchange. Chemical reviews 90: 935-967.

- Pal S (2010) Study of multi-site chemical exchange in solution state by NMR: 1D experiments with multiply selective excitation. J Chem Sci 122: 471-480.