Journal of Surgery

Download PDF

Case Report

The Silent Band: Not Loud Enough? Asymptomatic Gastric Band Erosion: A Case Report

AlHabib R1, Kayali N1, Al Rashed A1* and Al-Jaser W2

1Department of Surgery, Al Amiri Hospital, MOH, Kuwait

2Department of Gastroenterology, Al Amiri Hospital, Kuwait

*Address for Correspondence:

Al Rashed A, Department of Surgery, Al Amiri Hospital, MOH, 25 Gulf Road

13041, Kuwait City, State of Kuwait, Phone: +965 22450005 (Ext: 5500); Email:

asmaalrashed@dr.com

Submission: 02 July, 2022

Accepted: 01 August, 2022

Published: 06 August, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 AlHabib R, et al. This is an open access article

distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background: Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB)

is a common and an effective bariatric procedure. It involves the

placement of an adjustable band with an inflatable balloon at the

gastric cardia near the gastroesophageal junction. However, several

complications have been reported. These include port-site infections,

slippage of the band, and band erosion.

Case summary: A 44 years-old female who was found to have

an eroding gastric banding during esophagogastroduodenoscopy

incidentally. The gastric band was placed laparoscopically five years

prior to presentation. The band was removed successfully through

an endoscopic laparoscopic-assisted technique under general

anesthesia. Starting endoscopically, the eroded gastric band was

visualized and then broken using a mechanical lithotripter. However,

a small portion of the band remained embedded in the mucosa and

prevented the retrieval. Simultaneously, laparoscopy revealed intraabdominal

adhesions which were released, freeing the gastric band

into the stomach and allowing extraction of the gastric band using a

snare was completed endoscopically while ensuring examination of

intact gastric mucosa. The post-operative course and follow up were

uneventful.

Conclusion: Eroded LAGB can be silent necessitating life-long

follow-up. Endoscopic laparoscopic-assisted approach allows

definitive management, examining gastric wall integrity and leaks

simultaneously.

Keywords

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; Surgery;

Erosion; Weight loss; Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery; Revisional Surgery

Introduction

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB) is a bariatric

procedure that involves placement of an adjustable band with an

inflatable balloon at the gastric cardia near the gastroesophageal

junction. Placing this band will limit the amount of food consumption

promoting early satiety and progressive weight loss with time. LAGB

is a common bariatric surgery procedure ranking as the third most

common in the United States. However, several complications have

been implicated with the use of banding including pouch dilatation

(11%), band infection (1%) band erosion (28%) [1]. As with any

procedure, advantages and disadvantages must be highlighted. LAGB

is the least invasive bariatric procedure with an advantage of it being

adjustable and reversible. No anatomic rearrangements are done;

therefore, it has the lowest morbidity and mortality rates amongst

other bariatric procedures. However, slower rates of weight loss, up

to 40% to 54% of excess weight loss, are implicated in comparison

to other procedures like laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG)

and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (LRYGB); 49%-56%

and 55%-66% respectively [2]. Complications of LAGB may arise

including band slippage, band infection, and band erosion. Band

erosion is a late complication occurring at a mean of 22 months after

surgery. It may result either due to gastric wall ischemia from an

excessively tight band, mechanical trauma related to the band buckle

or thermal trauma from electro surgical energy sources used during band placement. Patients complicated with band erosion present

with abdominal pain, weight regain, nausea and vomiting. It may

also result in intragastric migration, partial or complete. Conversion

to other bariatric procedures such as LSG and RYGB are an option

once LAGB has failed whether due to inadequate weight loss or if

any complications have occurred. Gastric bypass has better outcomes

than gastric band procedures for long-term weight loss, type 2

diabetes controls and remission, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia

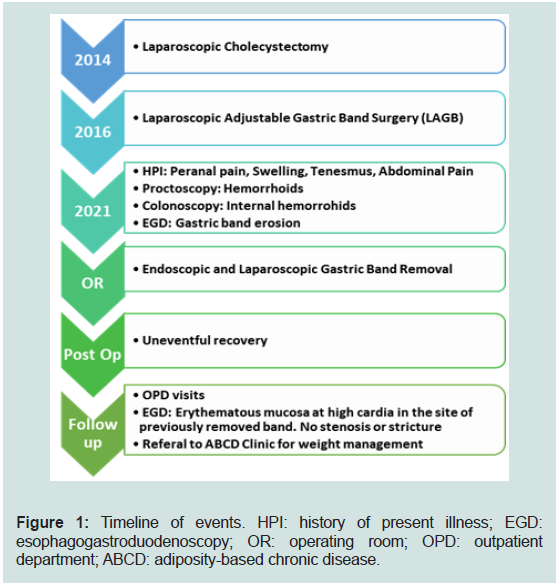

[3] (Figure 1).

Case Report

A 44-year-old female presented to the out-patient department

with a one-month history of perianal pain, swelling and tenesmus.

The perianal pain was sharp in nature, exacerbated by defecation and

lasted for multiple hours. She has a history of chronic constipation

for the past seven years and passes stool with straining, she had used local treatments such as ointments and suppositories. Additionally,

the patient reports abdominal pain and vomiting of one month

duration that occurred after heavy meal consumption with a

sensation of food impacted in the stomach. Past surgical history

revealed laparoscopic cholecystectomy seven years ago and LAGB

five years ago performed in another institution with a total of 17kg

weight loss. Her family history was positive for bowel cancer affecting

both her mother in the 7th decade and paternal uncle in his 8th decade.

The patient’s general appearance and vital signs were normal.

Her measurements were height 171 centimetres (cm), weight 87.2

kilograms (kg), and body mass index (BMI) 28.8 cm/kg. Abdominal

examination revealed mild tenderness in the epigastric area, without

distention, rigidity, or peritonitis. Proctoscopy showed grade II

hemorrhoids at 11 o’clock and grade I hemorrhoids at 3 and 9 o’clock

positions. The patient was advised for lifestyle changes and a decision

was made to proceed with colonoscopy to rule out malignancy and

esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for gastric band surveillance.

The colonoscopy showed internal hemorrhoids; however, EGD

showed gastroesophageal (GEJ) at 37 cm, normal esophagus, the

gastric band eroding the gastric wall (nearly 2/3 of band circumference

was visualized) and migrated upwards, just below the GEJ by 2 cm

(Figure 2). The rest of the examination was unremarkable. A Barium

meal showed that the gastric band is noted in the proximal part of the

stomach but appears relatively superiorly located with an increased

phi angle, measuring 70 degrees, suggestive of displacement with mild

superior migration of the gastric band and no leak. The findings were

consistent with the diagnosis of gastric band erosion. The diagnosis

and the management options with risks, benefits and complications

were discussed with the patient. She consented for endoscopic, and/

or laparoscopic and/or open laparotomy for eroded gastric band

removal.

The patient was admitted to the hospital and followed preoperative

assessment as per protocol. Preparation and coordination

with the intervention gastroenterologist team was arranged. The

patient was brought to the operating room, placed in supine position,

and underwent general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation.

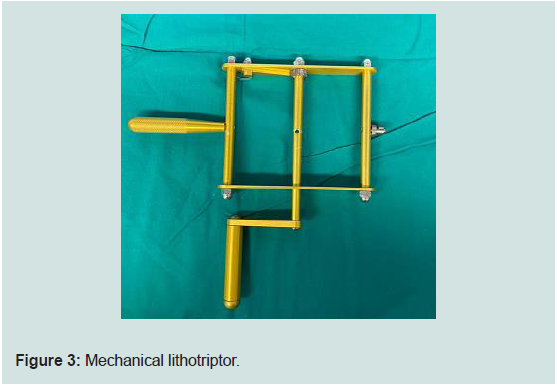

Starting with endoscopy, an eroded gastric band around 2 cm below

the GEJ at 39 cm was identified. A mechanical lithotripter was then

used to break the band successfully (Figure 3). However, one position

of the band system, most likely the buckle, was embedded in the

mucosa impeding the retrieval. After multiple attempts to pull it out,

a decision to proceed with laparoscopy was taken to assess if external

adhesive bands have prevented the endoscopic retrieval. The patient

was re-positioned to split-leg supine position. Pneumoperitoneum

achieved with 12-15 mmHg using Veress needle at Palmer’s point,

and then entry to the abdominal cavity in the left supraumbilical area

using a bladeless vesi-port 10 mm and a 30-degree camera was done.

Surveillance revealed a dilated stomach and small bowel with multiple

upper quadrant adhesions to the abdominal wall and the stomach.

The gastric band tube was followed to lead to the anterior portion of

the stomach. Few adhesive-bands were released using hook cautery

which facilitated in pushing the gastric band inwards to the gastric

lumen until no further resistance was felt. The EGD was performed

simultaneously to confirm that the entire gastric band is seen free

in the stomach cavity, which was then retrieved using a snare out

of the oral cavity (Figure 4). Integrity of the stomach was confirmed through insufflations of the stomach and filling the abdominal cavity

with sterile water. No bubbles were noted intra-abdominally while

the stomach was fully distended. The gastric-band reservoir was in

the epigastric subxiphoid area, and an incision was made to extract

it. All pieces of the gastric band tube system have been extracted

successfully. The port sites were inspected which were satisfactory for

hemostasis, pneumoperitoneum was then deflated, and the wounds

closed. On post operative day 1, the patient was vitally normal and

had only mild pain over the incision sites. A barium meal fluoroscopy

was performed, and no radiological signs of leak were seen. The

patient had an uneventful postoperative course, tolerated a fluid diet

with normal bowel function. On post operative day 2, the patient

was discharged home on proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) medication

and followed up in the outpatient clinic in the following week. Upon further follow up at OPD, she reports mild symptoms of food being

impacted in the stomach and vomited a few times; otherwise, she

was doing well and tolerating oral diet. An EGD was performed as

an out-patient to assess for stricture that showed an erythematous

mucosa at high cardia in the site of previously removed band with

no stenosis or stricture. She was advised to maintain a healthy diet

and lifestyle; continue the PPI medication and she was referred to the

Adiposity Based Chronic Disease Clinic (ABCD) for further followup

regarding weight maintenance after the LAGB removal. In her 6

months follow up the patient was asymptomatic.

Discussion

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band is a common and effective

procedure for morbid obesity. However, complications of LAGB are

not uncommon. This can include port-site infections, slippage of

the band, and band erosion. Gastric erosions after LAGB were first

reported in 1998 [4].

Gastric band erosion can present as an early or late complication.

Early erosions are usually related to the surgeon’s experience and port

site infection. Late erosions are related to port system dysfunction

and chronic ischemia. The incidence rate of gastric band erosion

ranges from 0.5% to 11% [5]. The variation in incidence rate could

be attributed to the type of the band and the surgical techniques.

Possible etiological factors of erosions are overfilling of the band

leading to gastric wall ischemia, suturing over the buckle of the band,

damage from the surgical instruments, and the dissection method.

Other causes are related to the patient’s factors including smoking,

use of NSAIDs, and consumption of alcohol.

The clinical presentation can range from asymptomatic with

incidental finding of erosion with routine endoscopy to failure to

achieve weight reduction, dysphagia, epigastric pain, and dehydration.

The erosion can be diagnosed by a CT scan. However, to confirm

the diagnosis of gastric band erosion, an upper gastrointestinal

endoscopy is needed.

Different techniques of gastric band removal have been reported in

the literature. This includes laparoscopic, endoscopic, and combined

endoscopic and laparoscopic techniques. The endoscopic technique

has proved to be successful in many cases. However, this technique

can only be done when more than 50% of the band has eroded

through the stomach and when direct visualization of the buckle is

possible. Adhesions can also limit the endoscopic retrieval of the

band. In a systematic review by Egberts et al, endoscopic removal was

not recommended because of the failure rates, the lengthy procedural

time, and the need for anesthesia and hospital admission [6].

In a case series by Chisholm et al, however, 46 cases out of 50

endoscopic retrievals were successful yielding a success rate of 92%

[7]. Similarly, Neto et al reported 82 cases of gastric band erosion with

a 95% success rate of endoscopic removal of the band [8].

Rodarte-Shade et al have described a hybrid technique for the

removal of eroded gastric bands. Adhesiolysis was done through a

laparoscopic technique. This was followed by an upper gastrointestinal

scope to visualize and remove the band trans-orally [9].

In our case, an endoscopic removal under general anesthesia was

attempted as more than 2/3 of the gastric band was visible; however, high resistance while pulling the band into the gastric lumen indicated

possible external adhesions. We proceeded to the laparoscopic

approach and found a few centimetres of the band visible and the tube

with multiple adhesions to it. After releasing the adhesions, the band

was smoothly pushed into the stomach and retrieved endoscopically.

Some of the advantages of laparoscopic-assisted endoscopic

retrieval of the band approach is to examine gastric wall integrity, to

test for leaks and to allow definitive management in that case with one

exposure to general anesthesia.

Kohn et al advocate for laparoscopic technique as this allows for

early intervention regardless of the percentage of erosion of the band

into the stomach [10].

In a retrospective review by Robinson et al that involved twentytwo

patients with gastric band erosions, one patient has undergone

a combined endoscopic and laparoscopic approach. This decision

was made based on the history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass followed

by banding of the gastric pouch, which has undergone a combined

endoscopic and laparoscopic approach. Adhesiolysis was done and

the band was retrieved endoscopically [11].

In one case report by Spitali et al, the authors have introduced

the use of a trans-gastric single incision laparoscopic surgery for the

removal of an eroded gastric band with an uneventful postoperative

course [12]. In a video case report, the authors preferred laparoscopic

trans-gastric removal in which the band was removed through

the trocar under direct visualization using both endoscopy and

laparoscopy. The reason for this is dense scarring in the anterior wall

of the stomach [13].

A trans-gastric endoscopic rendezvous technique was described

by Karmali et al to remove an eroded Molina gastric band. This

technique was preferred because the area of dense adhesions around

the stomach can be avoided [14].

Conclusion

Laparoscopic-assisted endoscopic retrieval of the band is a safe

and an effective approach that allows to examine gastric wall integrity

and to test for leaks. It also allows a definitive management with one

exposure to general anesthesia.

Acknowledgement

Author Contributions: Kayali N and AlHabib R, reviewed the

literature and contributed to manuscript drafting; Al-Jaser W,

revision of the manuscript, the gastroenterologist who performed the

endoscopy portion of the procedure; Al Rashed A, conception and

revision of the manuscript, the surgeon who operated the laparoscopic

portion of the procedure. All authors issued final approval for the

version to be submitted.