Journal of Surgery

Download PDF

Research Article

Old Dogs and New Techniques: Comparing Complete Robotic Adoption to Laparoscopic Surgery-A Single Institution Experience with Distal Pancreatectomies

Carter M. Powell BS1, , Christine MG Schammel2 and Steven D. Trocha3*

1Kenyon College, Gambier OH 43022, USA

2Pathology Associates, Department of Pathology, Greenville SC 29605,

USA

3Department of Surgery, Greenville Health System, Greenville SC

29605, USA

*Address for Correspondence:

Steven D.Trocha, MD,FACS Chief, GI Liver Division, Department of Surgery ,

Prisma Health, Upstate 900 W Faris, Greenville SC 29605, USA Phone: 864-

455-1200 Fax:864-455-1209 E-mail : Steve.trocha@prismahealth.org

Submission: 26 January, 2023

Accepted: 27 February 2023

Published: 02 March, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Carter M. Powell BS, et al. This is an open access

article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

The laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (LDP) is superior to

the open approach; however, proximal dissection, hand-assisted

(HA) approaches and conversion to open resection can be

improved upon. Robotic distal pancreatectomy (RDP) addresses the

limitations of LDP with better optics (3D), magnification, instrument/

visual stabilization and dexterity of the instrumentation. We sought

to investigate RDP vs. LDP and to introduce a new variable, tumor

distance from the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), to assess how

proximal the dissection was performed. A consecutive sample

of 45 patients who underwent minimally invasive distal pancreas

resection between 2/1/2012 to 6/30/2018 was completed. Typical

demographics and clinicopathologic variables were collected,

including outcomes. Overall, 22 LDPs and 23 RDPs, were evaluated.

No demographics, comorbidities, or ASA score were significantly

different between the cohorts. Neither differences in tumor size (LDP:

3.4cm +/- 2.8, RDP: 3.1cm +/- 1.9; p=0.80) or distance from the SMV

(LDP: 4.1cm +/- 3.0, RDP: 3.9 cm+/- 2.9; p = 0.89) were significantly

different. Positive margins were similar between groups; lymph nodes

were less with LDP than RDP (mean 6.4 and 10, respectively; p=0.09).

Post-operative complications and length of stay (mean 5.4 and 5.3

days, respectively) were similar between groups (p=0.27; p=0.94).

We show that converting to an entirely robotic approach for distal

pancreatectomies is safe, effective, with potentially better lymph

node dissection and a learning curve that demonstrates adoption at

any level of post residency training. Additionally, tumor distance from

the SMV/portal vein confluence could help quantify the theoretical

technical advantages of robotic distal pancreatectomy.

Keywords

Robotic distal Pancreatectomy; Adoption of New

Technology; Pancreatectomy; Robotic resection

Introduction

A complex and challenging procedure, distal pancreatectomy

(DP) has traditionally been performed via an open approach [1].

With advancements in technology, the first laparoscopic distal

pancreatectomy (LDP) was performed in 1994 by Cuschieri [2].

Compared to open surgery, LDP is associated with a reduction in

hospital stay, analgesic requirements, and blood loss [3-5]. Despite

the benefits of a minimally invasive approach, LDP has limitations.

The presence of large vascular structures, the retroperitoneal location,

and the concern for an inadequate margin clearance create obstacles

for surgeons who choose LDP, sometimes forcing them to convert to

a HA or open approach [5,6].

Robotic surgery represents the latest innovation in minimally

invasive surgery. Melvin et al. reported the first robotic distal pancreatectomy (RDP) in 2003, the same year Giulianotti et al.

published their series of robotic pancreas resections [7,8]. Robotic

surgery has allowed surgeons to overcome the limitations of LDP,

while maintaining a minimally invasive approach. Most notably, a

robotic approach provides a larger range of motion due to an internal

articulated endo-wrist. Robotics also offer a three-dimensional highdefinition

surgical view and tremor filtration, which can significantly

improve ergonomics for the surgeon [9]. Theoretically, these

technical advantages should afford the surgeon greater precision,

possibly providing them more access to tumors that would be not

considered for a laparoscopic approach and thus relegated to a HA

or open method.

Despite the benefits of robotic surgery, the adoption of RDP has

been slow. For veteran surgeons, adopting new surgical approaches

can be daunting. This hesitation is often due to the loss of tactile

feedback with robotics, which relies on “visual haptics,” and concerns

over increased operating time during the early learning curve as

well as possible increased cost associated with robotic surgery [1].

Furthermore, the adoption of a new surgical approach can be hindered

by a lack of training/experience, comfort with old approaches, and

concerns regarding outcomes. A growing body of literature has arisen

to compare the outcomes of LDP and RDP [1,5,10-13]. Meta-analyses

by Gavriilidis (2016) and Zhou (2016) investigate the findings of 8

retrospective studies and 2 prospective studies comparing LDP and

RDP [14,15]. RDP was found to be a safe and comparable alternative

to LDP, with no differences found between the two approaches.

The aim of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of

converting to an entirely robotic platform for distal pancreatectomies

by a veteran surgeon (old dog) and to introduce a new variable, tumor

distance from the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), as a measure of

precisely assessing how proximal the dissection was performed.

Methods

Following IRB approval, a retrospective analysis from 2/1/2012

to 6/30/2018 of 45 consecutive patients who underwent minimally

invasive distal pancreas resection at our tertiary institution was completed. Patients with multiple other operations, those without

followed up at our institution, and patients for whom complete

records were not available were excluded. All procedures were

performed by a single surgeon. The LDP population consisted

of patients who received treatment before robotic resection was

available at our institution (2/1/2012 to 4/30/2016). The LDP cohort

included those resections that involved hand assistance as well as

those requiring conversion to HAL. The RDP population consisted

of patients treated following the introduction of robotic resection

after 4/30/2016. This cohort included patients resected with robotic

technology only and those surgeries that were converted from

robotics to open resection.

Robotic surgeries were completed using the DaVinci® Robotics

(Intuitive, Sunnyvale, CA).

Preoperative imaging noted tumor size and distance from

the SMV/portal vein confluence as a comparison of the perceived

the difficulty of the resection and appropriate use of the surgical technique

(LDP+/- HAL; RDP conversion to open). For the purposes of our

study, we considered any patient that was started or changed to HAL

as an indication of a case outside a straight MIS approach.

All data were retrospectively collected and obtained from the

institution’s electronic medical records. The following data were

extracted: cohort characteristics, tumor location, intraoperative

outcomes (operative time, estimated blood loss, conversion rate,

complications), postoperative recovery (length of stay (LOS), postoperative

complications), and pathological outcomes (margin status

by frozen section and/or permanent section, tumor size, histologic

grade, lymph nodes harvested). Tumor location and distance from the

SMV were identified using pre-operative CT scans to trace the SMV/

portal vein confluence to the proximal edge of the tumor. The shorter

the distance the more proximal the dissection necessary for resection

and in principle; more challenging the surgery. Postoperative

complications were categorized according to the Dindo–Clavien

classification [16].

Data were stratified into LDP and RDP cohorts for statistical

analyses. The welch two sample t-tests were used to compare mean

age, BMI, length of stay, tumor size and location, console time,

estimated blood loss, and the number of nodes examined. Fisher’s exact

test was used to compare categorical variables including race, gender,

insurance status, ASA score, comorbidities, and post-operative

complications.

Results

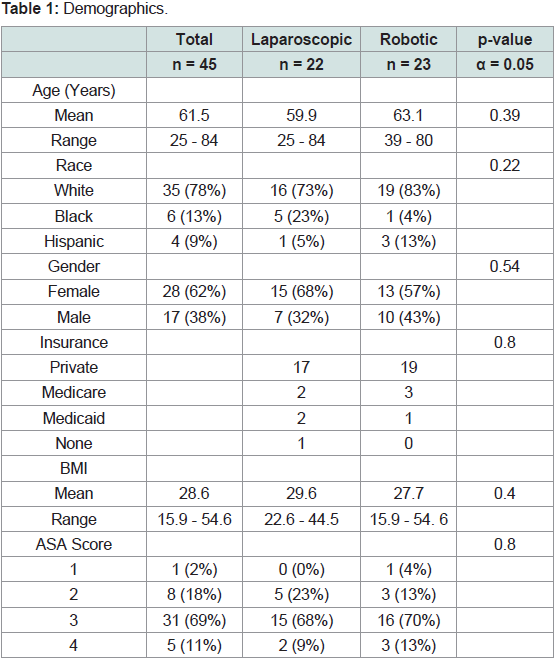

Following application of the exclusion criteria, 45 patients,

22 LDPs and 23 RDPs, were included in the study. In regards to

demographics, the two cohorts were not significantly different for

age (mean 59.9 and 63.1 years, respectively), race, gender, BMI (mean

29.6 and 27.7, respectively) and insurance status. The most frequent

American Society of Anesthesiologist’s score (ASA) in the cohorts

was 3; however, this was also not significantly different (Table 1). No

significant differences in comorbidities, previous cancer, or previous

surgery were observed between the two groups (data not shown).

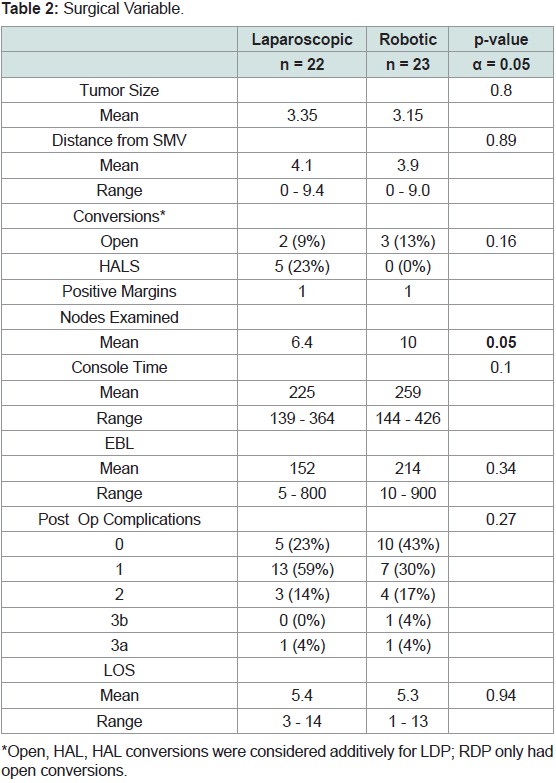

Interestingly, there were no significant differences for tumor size

(LDP: 3.4cm +/- 2.8, RDP: 3.1cm +/- 1.9; p=0.80) or distance from

the SMV (LDP: 4.1cm +/- 3.0, RDP: 3.9 cm+/- 2.9; p = 0.89) between

cohorts (Table 2). When considering conversions, HALS/open were combined for each cohort; overall, while the LDP cohort had more

conversions than the RDP cohort (LDP 32%; RDP 13%), this was not

significantly different (p=0.16; Table 2). Overall, five LDP resections

included a hand assist port (25%), two were converted to open (9%),

while 13% of RDP were converted to open (Table 2).

Additionally, while both cohorts had 5% of resections with

positive margins, LDP harvested less lymph nodes than RDP (mean

6.4 and 10, respectively); this was not significantly different (p=0.09;

Table 2). The estimated blood loss between the cohorts was also not

significantly different (p=0.34) nor was the console time (p=0.10;

Table 2). Post-operative complications and length of stay (mean 5.4

and 5.3 days, respectively) were similar between groups (p=0.27;

p=0.94).

The most common diagnosis for the LDP cohort was a mucinous

cystic neoplasm in five patients (23%). Serous cystic neoplasm was

the most common diagnosis for the RDP cohort, representing seven

patients (30%).

Discussion

As surgical techniques evolve and medical technology advances,

established approaches are replaced with more innovative procedures

that promise better outcomes. Yet before widespread adoption,

the safety, efficacy, and feasibility of these approaches must be

confirmed. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy has been shown to

safely improve patient outcomes when compared to a traditional

open approach; however, technical limitations remain [6]. A robotic

approach provides a solution to these technical limitations with its

internal articulation (seven degrees of freedom), 3D perspective, 10X

optics and tremor filtration [10].

The outcomes of LDP and RDP have been compared by numerous

retrospectivestudies. Meta analyses of the literature have concluded

that there is essentially no difference between LDP and RDP regarding

operative time, conversion rate, major morbidity, or post-operative

fistula [14,17]. In our study, we aimed to not only assess these measures

but also the feasibility of adopting a total robotic platform for a senior

surgeon. Anecdotally, adoption of new techniques can be hindered

by a lack of training/experience, comfort with established approaches

and concerns regarding outcomes. To these points, three important

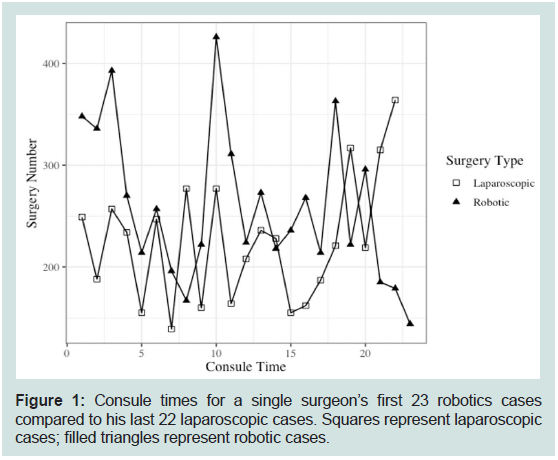

findings were demonstrated in our study. First, within the early

learning phase (20 cases) the senior surgeon was able to match his

laparoscopic outcomes with no increase in operative time, morbidity

or other post-operative complications. Thus, demonstrating that an

“old dog” can safely learn a disruptive technology without sacrificing

outcomes. A comparison of the first 20 RDP compared to our last

20 LDP highlight this (Figure 1). It is interesting to see that while

there was variability in the RDP times there was also a fair amount in

the LDP, despite these being our established experience (greater than

15 years of LDP resections). Few others have investigated the robotic

learning curve for distal pancreatectomy. Our outcomes mirrored

similar studies. A study comparing a single institution’s first 20

robotic cases with their later 17 cases found no significant difference

in operative time or conversion rate [1]. Another study assessed

the robotic learning curve over a single institution’s first 55 robotic

cases using a cumulative sum method and found that operative time

improved only over the first ten patients [19].

Figure 1: Consule times for a single surgeon’s first 23 robotics cases

compared to his last 22 laparoscopic cases. Squares represent laparoscopic

cases; filled triangles represent robotic cases.

While our study did not elucidate any significant differences

between the LDP and RDP cohorts, once distal pancreatectomies

were done robotically, LDP was no longer a surgical option at

our institution. Thus, surgeon selection bias was eliminated. Like

Daouodi [5], we sought to minimize this bias by evaluating LDP and

RDP cohorts based on time and not on patient or surgeon preference.

Since all DP performed at our institution were laparoscopic before

November 2016 and all DP performed after November 2016 were

robotic, we were able to reduce the effect of treatment selection

bias. Our results add to the growing evidence that RDP can be safely

adopted with proper training and preparation, especially by surgeons

with extensive LDP experience.

Second, while the conversion rates for LDP and RDP were not

significantly different in our study, the overall conversion rate for

LDP was greater than RDP (31% versus 13%), suggesting that this

phenomenon will continue with continued acquisition of skill and

more resection experience. Daouodi described a reduced conversion

rate for RDP and Duran concluded that RDP reduced morbidity

[5,12]. In hindsight this is not surprising when one considers the

improved optics (10x magnification), instrument degrees of freedom

(7 robotic vs 4 laparoscopic) and 3D visualization.

Third, in oncologic outcomes, the number of lymph nodes

resected has become a surrogate for completeness of resection and

improved prognostication [18]. We demonstrated that with RDP

the number of lymph nodes resected was greater than in LDP, 10

vs 6.4 nodes (p=0.09). Again, although we are in the early phase of

our adoption of this approach, we have nonetheless been able to not

only show equivalence but even improvement in some measures of

successful outcomes.

One of the reasons we elected to adopt robotics was the potential

ability to perform a more proximal dissection ( toward the SMV/

portal vein confluence). For LDP, the closer to the SMV/portal vein

the lesion was, the more likely we were to use a HALs approach or

dissect the tail and then make a midline incision (limited open) to

complete the resection at the neck. How to define and assess this

proximal dissection is difficult, outside of anecdotal experience and therefore we present a new variable that is potentially less subjective.

Tumor distance from the SMV/portal vein confluence was evaluated

in an attempt to quantify the anecdotal evidence for robotic surgery

facilitating more proximal dissections. We hypothesized that RDP

might allow surgeons to operate on tumors closer to the SMV/

portal vein confluence, but ultimately found no significant difference

in this metric. A confounding issue in this variable may have been

the resolution of imaging prior to resection regarding the ability to

recreate a 3D-high resolution map of the pancreas and its relationship

to the SMV/portal vein confluence. With more precise measurements,

3D modeling and larger sample size, tumor distance from the SMV/

portal vein confluence might be a valuable variable for future studies.

While the robotic approach has been shown to be a safe, feasible,

and an effective alternative to LDP, its widespread adoption has

likely been hindered by physicians’ comfort with laparoscopic

techniques, the relative lack of data on the RDP learning curve, and

the initial cost of robotics systems [Napoli, 2015]. We present a

single senior surgeon’s transition from laparoscopic to robotic distal

pancreatectomies to demonstrate that “old dogs” can safely learn

“new tricks”. Given that the surgeon had the greatest experience

with LDP and the least experience with RDP highlights and the lack

of difference in outcomes is remarkable and encouraging for other

surgeons.

Conclusion

Our experience suggests that converting to an entirely robotic

approach for distal pancreatectomies is safe, and effective, with

potentially better lymph node dissection and a learning curve that

demonstrates adoption at any level of post-residency training, even if

that is years later. The superiority of the robotic approach over a more

traditional laparoscopic approach continues to be debated; however,

the introduction of a new variable, tumor distance from the SMV/

portal vein confluence, could help quantify the theoretical technical

advantages of robotic distal pancreatectomy. As the technology

continues to evolve and more data are presented, it will be important

to continue these investigations in larger, randomized clinical trials,

especially with regard to long-term outcomes and physician learning

curves.

Acknowledgement

Carter Powell BS, Christine MG Schammel

PhD have no competing interests or financial ties to disclose.

Dr. Trocha is a personal paid consultant for Castle Biosciences,

Johnson and Johnson, and Boston Scientific; this study was not

affected by any of these companies.

No funds, grants or other support was received in the execution

of the study or preparation of the manuscript.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the

current study are not publicly available, but are available from the

corresponding author on reasonable request and the procurement of

a data sharing agreement with Prisma Health Upstate.

Ethics:

This research study was conducted retrospectively from data obtained for clinical purposes. We consulted extensively with the

IRB of Health Sciences SC who determined that our study did not

need ethical approval. An IRB official waiver of ethical approval

was granted from the IRB of Health Sciences SC and Prisma Health

Upstate.