Journal of Surgery

Download PDF

Case Report

Open Repair of Pediatric Aortoenteric Fistula from A Remote Gastric Transposition in Congenital Esophageal Atresia: A Multidisciplinary Approach

Snyder KB1,2*, Farnell C3, Buonpane C1,2, Gierman JL2,3, Hunter CJ1,2 and Landmann A1,2

1Division of Pediatric Surgery, Oklahoma Children’s Hospital, 1200

Everett Drive, ET NP 2320 Oklahoma City, USA.

2The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Department of Surgery, 800 Research Parkway, Suite 449, Oklahoma City, OK USA.

3The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Department of Vascular Surgery, 800 Research Parkway, Suite 449, Oklahoma City, OK USA

2The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Department of Surgery, 800 Research Parkway, Suite 449, Oklahoma City, OK USA.

3The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Department of Vascular Surgery, 800 Research Parkway, Suite 449, Oklahoma City, OK USA

*Address for Correspondence: Katherine B. Snyder, Department of Pediatric Surgery Oklahoma Children’s Hospital, Oklahoma City, USA. Email Id: Katherine-snyder@ouhsc.edu

Submission:11 January 2024

Accepted:07 February 2024

Published:12 February, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Snyder KB, et al. Powell BS, et al. This is an open

access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License,

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords

Esophageal Atresia; Aortoenteric Fistula; Ulcer; Pediatric Surgery; Vascular Surgery

Abstract

A 12-year-old male with history of long gap esophageal atresia

with a gastric transposition at one year of age presented with multiple

episodes of hematemesis. He recently had been prescribed high

dose NSAIDs for pericarditis. He underwent multiple endoscopic

cauterizations of a large gastric ulcer and despite this required MTP.

CTA was obtained showing hypoattenuation of the gastric conduit

along the aorta near the area that was cauterized. The patient

underwent a left-thoracotomy and gastrotomy. Once hematoma was

evacuated, a large pulsatile bleed was encountered. Pressure was

held and control of the aorta was obtained. The gastric conduit was

dissected off the aorta, revealing a large defect. The gastric conduit

was repaired, the aorta was repaired with bovine pericardium and

pleural flap was placed. On POD 8 a swallow study demonstrated no

leak and the patient was discharged on POD 15. Outpatient follow-up

CTA demonstrated an intact repair.

Introduction

Aortoenteric fistulas are a fairly rare cause of gastrointestinal

bleeding and if seen, it is typically seen in adults [1,2]. They

are historically separated into primary aortoenteric fistula and

secondary aortoenteric fistulas [1,2]. Primary AEF is defined as a

spontaneous communication between native aorta and any portion

of the gastrointestinal tract resulting from compression against

an abdominal aortic aneurysm [1,2]. Secondary AEF is defined as

typically resulting from a complication following vascular surgery

and rarely GI surgery [1-3]. When noted to be a sequala of GI

surgery, AEF characteristically presents 2-3 weeks following the

operation, typically an esophagectomy or esophago-gastrectomy at

the anastomosis site [4-6]. Patients typically present with massive

hematemesis and regardless of type of AEF, the mortality rate

for AEF is high, with it reaching as high as almost 60% with an in

hospital mortality rate almost 30% [7]. There is little to no literature

demonstrating AEF in the pediatric population. We present a case

of a 12-year-old male presenting with a thoracic gastro aortoenteric

fistula following a gastric transposition for long gap esophageal

atresia when he was 1-year-old.

Case report

The patient is a 12-year-old male with a history of long-gap

esophageal atresia with a gastric transposition at one year of age

presented with multiple episodes of hematemesis. Interval history

involved primary care physician diagnosis of pericarditis-associated

with COVID vaccination, requiring high dose ibuprofen one month

prior to his presentation for hematemesis. Four weeks following the

diagnosis of pericarditis, he experienced hematemesis for which three

attempts at endoscopic cauterization of a large gastric ulcer were

attempted and unsuccessful. Computed tomography angiography

(CTA) was obtained that showed hypoattenuation of the gastric

conduit along the aorta near the area that was cauterized [Figure 1].

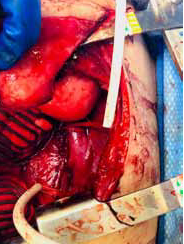

Due to failure of non-operative management and concern for

AEF, operative intervention with pediatric surgery was indicated.

Extensive operative planning was performed including resuscitative

line placement, preparation for possible cardiopulmonary bypass,

and vascular and cardiac surgery on standby.The patient underwent

a left thoracotomy and gastrotomy. Once hematoma was evacuated

from the conduit, a large pulsatile bleed was encountered. Pressure

was held and proximal and distal control of the aorta was obtained.

Vascular surgery was consulted emergently intraoperatively and the

gastric conduit was dissected off the aorta, revealing a large defect

Figure 1: CTA demonstrating hypoattenuation of the gastric conduit along the

aorta near the area that was cauterized with concern for aortoenteric fistula.

and an aortoenteric fistula [Figure 2]. Proximal and distal control of

the aorta was obtained using umbilical tape. A 20F chest tube was

then used as a shunt and the aorta was clamped. Pediatric surgery

worked to separate the gastric conduit from the aorta, while vascular

surgery repaired the aorta with a rifampin soaked bovine patch sewed

in using 4-0 prolene suture. Upon removal of the gastric conduit from

the aorta, a large ulcer in the posterior aspect of the stomach was

discovered and repaired with several figure of eight 3-0 PDS and the

gastrotomy was closed with a blue load 60mm stapler. Cardiothoracic

surgery was called intraoperatively to perform a thoracic pleural flap

placed between the gastric and aortic repair as a buttress.

Post operatively, he was resuscitated in the pediatric intensive

care unit for several days. Post-operative medications included IV

antibiotics for a 6-week course, twice daily proton-pump inhibitor,

and Plavix which was started on post-operative day (POD) three. On

POD 8 we performed a swallow study demonstrating no leak and

diet was advanced [Figure 3]. He was discharged on POD 15 with an

outpatient follow-up with pediatric surgery and vascular surgery and

progressed well.

Discussion

Aortoenteric fistulas are rare, however if found they are

typically in the adult population predominantly associated with

aortic aneurysms or following vascular operations [1,3,7,8]. Nonaneurismal

aortoenteric fistulas a are extremely rare, but have been

reported in adults to be associated with carcinomas, tuberculosis,

abscess, radiation, or duodenal ulcers [8]. The presentation of these is

usually with gastrointestinal bleeding, and if from an operative cause,

typically within one month postoperatively [4]. Management in the

adult population often consists of endovascular stent placement and

resection and reconstruction with intestinal reconstruction [6,7].

Our case is unique in many ways, our patient is a 12-year-old male

without history of vascular disease or surgery who presented with

gastrointestinal bleeding in the form of hematemesis 11 years post

operatively. He was prescribed high dose ibuprofen one month prior

to his episodes of hematemesis which almost certainly led to the

development of the gastric ulcer found intraoperatively eroding in the

aorta. His unique anatomy following the gastric pull through likely

contributed to the ease of development of the fistula from the gastric

ulcer. Our patient was trial managed non-operatively multiple times

with failure leading to hemorrhagic shock. We would recommend

early involvement of a pediatric surgery team when dealing with

unique anatomy and continued hematemesis following endoscopic

intervention.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of this nature in pediatrics

and it presented several challenging components. Our institution

is fortunate to have all needed available specialties for adequate

operative repair. Obtaining proximal and distal control in this

instance was crucial, we were able to use a chest tube as a shunt to

avoid prolonged ischemic time. Ideally, the aorta would have been

repaired primarily, however the ulcer site tissue was extremely friable

and thus sutures did not hold. Rifampin soaked bovine patches have

shown good results in adult literature for vascular repair, and we

would recommend that for treatment should primary repair not be

attainable. Removal of the ulcerated gastric tissue and repair of the

area is crucial in this operation as well, and we were able to primarily

repair this without evidence of leak. In a hostile field, the worry

would be that this would recur for this patient, which prompted us

to perform the thoracic pleural flap to act as a barrier between the

stomach and the newly repaired aorta, which is crucial in this case. He

recovered well postoperatively and has close follow up surveillance

with outpatient CTA demonstrating an intact repair [Figure 4]. We

would recommend follow up imaging with CTA’s at 3 months, and

one year due to the serious nature of this aortoenteric fistula and his

unique anatomy.