Journal of Nutrition & Health

Download PDF

Research Article

*Address for Correspondence: Mary W. Murimi, College of Human Sciences, Department of Nutrition, Hospitality, and Retailing, Texas Tech University, PO. Box 41240, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA, Tel: +1 (806) 843-1812; E-mail: mary.muimi@ttu.edu

Citation: Murimi MW, Chrisman M, Diaz-Rios LK, McCollum HR, Mcdonald O. A Qualitative Study on Factors that Affect School Lunch Participation: Perspectives of School Food Service Managers and Cooks. J Nutri Health. 2015; 1(2): 6.

Copyright © 2015 Murimi MW, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Nutrition and Health | ISSN: 2469-4185 | Volume: 1, Issue: 2

Submission: 13 November, 2015 | Accepted: 21 December, 2015 | Published: 26 December, 2015

Data analysis

In response to the interview questions, four main themes emerged, in addition to other issues raised by the food service staff. First, there was a clear need for more space and personnel to implement the new menu. Second, food service staff was resistant to change and did not fully support the new menu. Third, there was confusion regarding the healthfulness of the new menu. Finally, there was a concern for serving what the students preferred, and how the changed menu was leading to food waste.

A Qualitative Study on Factors that Affect School Lunch Participation: Perspectives of School Food Service Managers and Cooks

Mary W. Murimi11*, Matthew Chrisman1, Lillian K.Diaz-Rios1 and Heather R. McCollum2 and Olevia Mcdonald2

- 1College of Human Sciences, Department of Nutrition, Hospitality, and Retailing, Texas Tech University, USA

- 2School of Human Ecology, Louisiana Tech University, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Mary W. Murimi, College of Human Sciences, Department of Nutrition, Hospitality, and Retailing, Texas Tech University, PO. Box 41240, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA, Tel: +1 (806) 843-1812; E-mail: mary.muimi@ttu.edu

Citation: Murimi MW, Chrisman M, Diaz-Rios LK, McCollum HR, Mcdonald O. A Qualitative Study on Factors that Affect School Lunch Participation: Perspectives of School Food Service Managers and Cooks. J Nutri Health. 2015; 1(2): 6.

Copyright © 2015 Murimi MW, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Nutrition and Health | ISSN: 2469-4185 | Volume: 1, Issue: 2

Submission: 13 November, 2015 | Accepted: 21 December, 2015 | Published: 26 December, 2015

Abstract

Background: High levels of obesity and diabetes have created aneed to improve the diets of adolescents, particularly in school settings. School food service staff has the ability to implement changes in foods served at school, but their perspective has not been well-studied. The purpose of this study was to describe the perceptions of school food service staff regarding the implementation of a new healthier menu.Methods: Five focus groups were conducted with food service staff after the implementation of a new menu in the Lincoln Parish School District in Louisiana. Four researchers transcribed and coded the sessions.

Results: Four themes emerged: The new menu requires more space and personnel; food service staff was resistant to change; there was confusion regarding the healthfulness of the new menu; and concern for serving what the students preferred.

Conclusions: Food service staff perceived the new menu as unappealing to students, not healthier and requiring more resources to implement. Not involving the staff in the modification process resulted in lack of support for the new menu. Involving food service staff in all stages of major menu changes is crucial for proper implementation and success of school nutrition policies.

Keywords

School menu; School food service; School nutrition policyAbbreviations

NSLP: National School Lunch Program; SNDA: School Nutrition Dietary Assessment; SMI: School Meal InitiativeIntroduction

A number of studies have indicated how childhood obesity is ubiquitous and early prevention is critical [1-3]. Recent estimates indicate approximately 31.8% of children 2-19 years of age are overweight or obese in the United States [3]. Unhealthy diets are one likely culprit contributing to weight issues [4]. Since children may spend a large portion of their day at schools, consuming up to 50% of their total calories while there, the school food environment presents a logical opportunity for improving children’s dietary patterns, preferences, and food intake [1,5]. Schools have therefore been the focus of efforts to reduce obesity and diet-related diseases among school age children [6].The Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 required education agencies sponsoring school meal programs to involve representatives of the school food authority, such as cafeteria workers and managers, when developing a school wellness policy, which can include changes to foods offered at school meals [7].

Foodservice staff members play a critical role in providing safe and healthy meals at school and the majority of them take their responsibilities for student well-being seriously while being committed to the children they serve [8]. They often get to know their students very well, putting them in a unique position for disseminating nutrition education and modeling healthy eating practices [9]. Moreover, food service staff members are the ultimate executors of meal-related policies. Therefore, it can be expected the more they understand the relevance of such policies, and the more they feel involved in the decisions that affect their everyday tasks, the more likely they will embrace change, and thus, policy implementation will have a better chance of success. However, few studies have examined the viewpoints of cafeteria workers and managers when developing menus for high school students, thus there is a need to describe their perceptions towards the foods they serve and the conditions under which they serve them. The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) includes participation by over 31 million students and therefore it is imperative to understand the challenges and perspectives of the cafeteria staff as they are the implementers of the program [10].

In 2012, the school menus from the Lincoln Parish School District in northern Louisiana underwent a modifications process that started with the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004. The changes were made by the food service director in an effort to improve the nutritional quality of the school menu. The result of the modification resulted in initial poor acceptability of the new menu by students and resistance of the new process of food preparation by the food service staff. Changes to the menu included elimination of high calorie items such as cakes and fried foods, while new cooking methods included baking instead of frying foods, modifying recipes to include whole wheat flour, reducing the amount of fat and sugar as ingredients, and adding new items to the menu, such as more fruits and vegetables. The purpose of this study was to understand the perspectives of the food service staff regarding the modified menu, including the challenges they faced and their recommendations in improving the acceptability of the menu by the students.

Methods

Setting and participantsThe Lincoln Parish School District comprises 15 schools serving 5,921 students from grades Pre-K through 12. Lincoln County is 40% rural with about 55% of the population being Caucasian and 41% African American. About 85% of the residents completed at least high school, and 34% hold a bachelor’s or higher education degree. About 28% of the people in this area have an income below poverty level [11].

All cooks and managers of the junior high and high school from the school district participated in this study. Participants were recruited through the school district main office by the school food service director. Focus groups were scheduled after school or on non-school days to accommodate all participants. Participants were compensated by the school system for their time during the focus group discussions. The study was approved by an Institutional Review Board at Louisiana Tech University and all participants provided written informed assent.

Procedure

Five focus groups were conducted during the 2011-2012 school year; 6 months after menu changes took effect. All focus group sessions were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. They ranged in size from 7 to 10 members and lasted approximately 90 minutes. In order to capture any potential differences in perspectives between the food service cooks and managers, three focus groups were conducted separately among the cooks and two focus groups among the managers. A focus group topic guide was formulated and evaluated for clarity and flow by the research team based on published protocol [12]. Two researchers experienced in focus group interviews moderated all 5 sessions while two other members of the research team recorded the sessions, observed and documented supplementary field notes. These notes included comments on the conversation, the tone of voice, body language, and descriptive words. The focus group method was chosen due to the ability of participants to answer why and how questions and provide perspectives that cannot be captured in a survey.

The discussions were expected to afford the food service staff an opportunity to discuss their opinions and observations in details. Participants were asked to describe the food production process, challenges faced during meal preparation and serving times, how they were trained to cook and serve the menu items, how they prepared students to accept the menu, and their perspective on how the students’ reacted to the changes. In addition, they were asked to provide suggestions for improvements (Table 1).

Data analysis

Four experienced researchers independently coded the transcripts and conducted a content analysis. This process included organizing quotations from the focus groups in a table based on common categories and issues, which was followed by placing these data into broader themes in a systematic manner. The researchers each looked for patterns among these categories and derived meaningful conclusions from the coded comments. After the coding process was finalized by each researcher individually, researchers met to discuss and compare results, agree on themes, select relevant quotations, and reach consensus where discrepancies emerged [13,14]. All of the researchers agreed on the final themes resulting from the focus group quotations.

Results

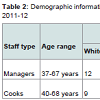

A total of 45 food service staff members (30 cooks and 15 managers) participated. The majority of the managers were white (80%, n=12) and 20% (n=3) were black. On the other hand, a majority of the cooks (70%) were black and 30% were white. All of the participants were female. Other demographic information for the participants is shown in (Table 2).In response to the interview questions, four main themes emerged, in addition to other issues raised by the food service staff. First, there was a clear need for more space and personnel to implement the new menu. Second, food service staff was resistant to change and did not fully support the new menu. Third, there was confusion regarding the healthfulness of the new menu. Finally, there was a concern for serving what the students preferred, and how the changed menu was leading to food waste.

Need for more working space and reliable personnel

The modified menu had additional items the food service staff had to prepare, and additional lines that students had to go through (salad lines, sandwich lines). This resulted in a need for more space and additional personnel to handle the new workload. In addition, a major part of their personnel were substitute cooks that were not reliable as expressed below. The cooks and managers expressed frustration with lack of sufficient space as a result of additional items in the menu: “My biggest problem is I had one line that I had to serve, but [now] I’m having 3 different lines on the same space”. Another manager expressed their frustration with the lack of space and adequate staffing, mentioning: “we don’t have room on our lines for all the food items”, and “lack of manpower to do all of the work that needs to be done, seems to be the biggest problem... It’s too much food”. One cook noted how this was not an isolated concern, but that it “is a problem with all of the schools. It’s just too much for two people to do”.

In addition to the limited personnel, both cooks and managers felt like the increased variety in the new menu compromised food quality. This was explained by one of the cooks who acknowledged the difficulty of keeping food at safe temperatures: “To keep the food warm is a challenge…there is so much food it’s hard to keep it warm on the line. We just can’t do it… in a very limited space”.

As a solution, managers suggested adding full time employees and adding space: “make more room in the cafeteria and we really need full time workers not part time workers because them subs can walk out just anytime; you get a good one and then it takes you to go through 10 before you get another good one”. All the managers agreed that personnel is their greatest challenge and that part-time or substitutes are unreliable: “that is just about ridiculous for a school to be set up like you’re set up and they won’t hire you somebody cause I need one, I got a full time sub too and I got one of my good full time subs quit because he wouldn’t be hired full time, and so now then I’m using whoever and whoever ain’t no good, they don’t show up”. Some of the managers shared tips for potentially dealing with the lack of personnel, including: “we pre-make our salad and we keep it on ice and put it on the head of the line”.

Resistance to change

The food service staff indicated that they were not consulted when the school district’s menu was changed by the food service administrators. As a result, many of them were resistant to the changes, and several statements express their feelings towards the new menu: “The menu items don’t even go together”, “the kids don’t like it,” and “they’re tired of the same old thing”. Regarding the menu changes, one of the cooks stated that “we haven’t really been told what the purpose is”. When asked to describe the students’ reactions to the new menu, the managers answered that students were disappointed due to things that were missing from previous menus that the students were used to and enjoyed. In fact, one of the managers mentioned that a goal for their cafeteria was to “change those menus and get items on there that these kids like”.

The managers mentioned that they also had no role in the menu changes, but had to endure complaints from unhappy parents, mentioning that the parents “don’t like the menu change” and “it gets taken out on the managers a lot”. As a result, the managers expressed a desire to let parents of the students know that they were not the ones to make the menus.

Confusion regarding healthfulness

The food service staff members were asked if they thought the new menu was healthier. In addition to the revised menu resulting in more work, both the cooks and managers did not believe the new menu was any healthier. In regards to one days’ menu, one cook stated bluntly, “It’s the worst menu we’ve ever had”. Another added: “Healthy foods? What are y’all healthy foods? Cinnamon toast is not healthy. You butter the pan, put the toast on it, butter the top, then put cinnamon and sugar on top of that. What’s healthy about that”? One cook mentioned that some items may be healthy but others are not: “the wheat rolls are healthier, but this fruit we have, sometimes it has heavy syrup and probably has more calories than a cookie. Some of the other stuff has butter in it, also the macaroni and cheese isn’t healthy”. Another cook provided a more descriptive example: “The foods come already processed. We can’t fry anything anymore; we have to bake the French fries. So everything comes breaded and fried from the factory, but you bake it. It’s not healthy, it labels questionable items healthy. Cinnamon rolls aren’t healthy either. Similarly, the meat patties they’ve already been fried, then you put them in the oven; there is all this grease that comes out of them. We have to drain off”. Other statements about healthfulness included: “Oatmeal, but they have sugar added in”; and “the old menu was not healthy, but this one isn’t healthy either. It is no better”.

Managers had contradictory viewpoints regarding the healthfulness of the new menu. On one hand, “we were told not to use sugar, but we have glazed carrots in our menu; well, how are you going to glaze carrots if you don’t put sugar on them? We turn around and add things that we’re cutting; we’re turning around and adding the fat and sugar back into the vegetables that are supposed to be healthy”. And another manager mentioned that “the main menu items are not any healthier than what we have been doing”. However, other managers provided an alternative view of the healthfulness, saying that: “I think it’s good that we don’t have all the baked desserts”, and “the menu that we’re having isn’t bad, the problem is it’s something that the kids don’t want”.

Students’ preferences

Both the cooks and the managers strongly expressed their concern for the poor acceptability of the modified menu by the students. The cooks seemed to understand students’ preferences, mentioning that “[the menu] is not kid friendly”, “the children are unhappy because they don’t like the new menu” and “if they could, they would eat hamburgers and French fries every day”. Another cook added an empathetic tone regarding the students’ preferences: “I know one thing that mine don’t like and it’s the potato au gratin with the fish sticks; they would rather have fries or macaroni and cheese…but macaroni and cheese has been taken completely off the menu”.

Cooks seemed to know and recognize the basis of food choices or rejection, as expressed by one of them: “If the students do not know what the food is or if it is different from what they are used to they will not eat [it]. We only feed half of our students; we’ve got a low number of students eating our food… they go to concession or they don’t eat, or they bring in lunch”.

One of the managers expressed concern for the students’ rejection of the new menu, stating that “I understand the kids need to eat healthy, but when you’re feeding them something that they’re not going to eat, you’re not providing them any nutrients that way”. Another manager agreed with that sentiment by mentioning that “If you leave the cheese out of it, they’re not going to touch it; it’s going to go in the garbage”. Some of the managers tried to accommodate students’ rejection of menu items, as vented by one of them: “We could have cornbread and they won’t touch it because they don’t know what it is. So I’ve stopped serving cornbread and went to rolls”.

Several statements indicated that students at each school had specific preferences. For example, one cook stated that students love oven-fried chicken while another cook at a different school mentioned that students did not like the oven-fried chicken. As a result, one of the managers discussed that there is a “need to find what’s right for each school”. There was some consensus among the schools related to food items that were universally disliked, such as wheat rolls and wheat toast, and sweet potato fries.

Food waste

Finally, many cooks mentioned how students’ preferences led to waste, as one of them stated: “they don’t eat a lot of this stuff. I see more going into the trash can… All the kids could eat there if we offered them things that they would enjoy” and another cook mentioned that “We also throw away as much food as we cook”. Specific examples of what was wasted as mentioned by the cooks included: “pans and pans of fruit go into the dumpster,” and “they don’t like the broccoli salad, that’s a lot of money being thrown away”.

Discussion

This study described the perceptions of cooks and managers pertaining to changes in the school menu in an attempt to improve school meals in compliance with the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004. The study findings indicate the importance of including school food service staff when changing a school menu.The food service staff members identified lack of adequate space and personnel as important barriers in implementing prescribed changes. Staff indicated that a concern that more workers were needed to implement menu changes. This supports Conk and colleagues’ finding that a lack of extra labor was a barrier encountered when trying to reform school lunches [15]. Additionally, a recent report on school kitchen needs across the country revealed that more than half of school districts in the US need kitchen infrastructure changes, with the top challenge being additional space for storage, preparation, or serving [16]. This issue was discussed by both cooks and managers in our study.

One of the concerns for both cooks and managers was the fact that low acceptability of the new menu led to significant food wastage. This concern is in line with findings of the second School Nutrition Dietary Assessment (SNDA) in which food service managers from elementary schools reported increased waste of main dishes and breads as a result of modifying their menu to be in line with Dietary Guidelines [17]. While a certain volume of food waste is expected, maximizing the amount of food eaten is crucial not only for economic purposes but also for nutritional reasons, as school meals may represent the only food eaten each day for some low-income children [18]. A study conducted in a low-income urban area in Massachusetts found considerable amounts of food wasted in schools correlated with deficiencies of important nutrients such as fiber, iron, calcium, and vitamin C among students [19].

Other studies have found cooks usually lack training in menu planning, nutrition, healthy cooking techniques, and adequate portion sizes [20,21]. In an effort to increase food acceptability by the students, the cooks and managers in this study indicated they altered the new menu by adding fat, salt, and/or sugar to recipes. The extent to which the food service staff was allowed to make changes to the menu is unknown; however, judging by participants’ comments, some level of flexibility existed. Properly trained cooks and managers would be more likely to make modifications without sacrificing the nutritional quality of the food prepared. Although the cooks rightfully questioned some unhealthy options in the new menu-they did know which items were not healthful-they did not have the skills to prepare good tasting foods that were both healthy and attractive to the students. This reveals a disparity between what they know and what they are actually capable of doing, which is particularly concerning given that the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act was signed into law and mandates specific nutrition standards in school meals [22].

According to the most recent SNDA, less than a third of the school food service staff has participated in nutrition education activities and only 28% have received classroom nutrition education [18]. Nutrition education to food service staff requires time and well-coordinated efforts from those involved, as well as a plan that considers followup and reinforcement [23]. Nonetheless, making the investment for nutrition education is crucial, as equipping the staff with nutrition education and cooking and food safety skills are critical for the school food service staff to be effective in preparing healthy meals. In response to this need, training and technical assistance for food service staff was recently made available by the US Department of Agriculture to assist in monitoring and compliance with the most recent standards for school meals [24]. Methodologies such as the Coordinated Approach to Child Health have demonstrated the significance of integrating food service staff training for a successful implementation of school wellness programs that comply with mandated regulations [25].

In addition to being insufficiently trained prior to the adoption of the new menu, managers felt their opinion and knowledge of student’s preferences was not utilized during the menu changing process. Failing to sufficiently involve the staff in the process of change and providing clear explanation of the purpose may have contributed to their lack of enthusiasm to the new menu, which contradicts their role as actors promoting good eating practices among children [8,18]. Instead, both cooks and managers in this study were sympathetic to student concerns about the foods offered instead of promoting the new menu. This supports the findings of Burden and colleagues as well as Cho and Nadow, that food service employees prefer to offer familiar foods students enjoy, and indicates that food service staff should be included during a menu change process [20,23].

Although parents have been identified as crucial to promoting student support of food changes in the school, their perspective was not assessed in this study [23]. Conk and colleagues reported that resistance to school lunch reform was often supported by parents [15]. Like the food service staff, parents are critical stakeholders for the school lunch program and, therefore, it is important to also engage them early in the process of menu modification to get their input and explain the rationale for change.

Limitations

Although this study provides important perspectives from the food service staff that can improve school child nutrition programs, the source of information is limited to one school district, thus, results may not be generalizable to other schools in the country. All statements made during the focus groups represent personal observations of the food service staff and not necessarily facts about the school menu and changes made to it. Likewise, information pertaining the capacity and conditions of school food service facilities was not obtained, thus, it was not possible to perform a triangulation against impressions of food service staff. We also did not collect in-depth demographic data due to the small sample size and thus are not able to analyze potential group differences. Finally, although participants were informed about the confidential nature of the study, the possibility of response bias due to social desirability cannot be discarded.Conclusions

Currently, meals served at schools participating in the NSLP and the School Breakfast Program are required to follow the School Meal Initiative (SMI) standards, which require 33% and 25% of the daily calorie requirements are provided by lunch and breakfast respectively, and no more than 30% of those calories come from fat [18]. Despite progress being made in regards to meeting individual standards, the most recent SNDA has reported as little as 7% of the schools in the US served food that met all of the SMI standards [18]. The need for a stronger consideration of food service staff perceptions, experience, and needs during the process of changing or improving school menu and training the cooks and managers on the desired practice is critical as evidenced by this study.According to the managers and cooks in this study, the adoption of a new healthier menu requires additional resources not provided as part of the change process, including time, space, and manpower, as well as training in nutrition and healthy food preparation. Equipping food service staff with nutrition education must be considered a cornerstone in the process of implementing school policies aimed to improve student’s nutrition status, as they represent nutritional gate-keepers and potential healthy-eating advocates in these settings. Managers felt they were not engaged enough in the process of changing the menu, whereas cooks believed the new menu resulted in food waste and lower student participation; as a result, they were not supportive of the modification. The implications of these findings point to the importance of considering the input of the school food service staff while making changes. Similarly, it is just as important to provide nutrition education and healthy food preparation training to the food service staff in an effort to gain their support for menu changes. For example, As a result of these findings, two policy changes were effected in the study district. Taking the Serve Safe food safety training became mandatory for all the kitchen staff and a series of cooking and food presentation training were implemented in the district. In addition, future studies should examine in-depth the role parents may play in influencing their children’s food choices at school, as well as their perspectives on how school meals should be changed.

References

- Perlman SE, Nonas C, Lindstrom LL, Choe-Castillo J, McKie H, et al. (2012) A menu for health: changes to New York City school food, 2001 to 2011. JSch Health 82: 484-491.

- Reed SF, Viola JJ, Lynch K (2014) School and community-based childhood obesity: implications for policy and practice. J Prev Interv Community 42: 87-94.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM (2012) Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010.JAMA 307: 483-490.

- Millimet DL, Tchernis R, Husain M (2010) School nutrition programs and the incidence of childhood obesity. J Hum Resour 45: 640-654.

- Story M, Nanney MS, Schwartz MB (2009) Schools and obesity prevention:creating school environments and policies to promote healthy eating and physical activity. Milbank Q 87: 71-100.

- Tsui EK, Deutsch J, Patinella S, Freudenberg N (2013) Missed opportunities for improving nutrition through institutional food: the case for food worker training. Am J Public Health 103: e14-e20.

- 2004) S. 2507 (108th): Child nutrition and WIC reauthorization act of 2004.

- McCain M (2009) Serving students: A survey of contracted food service work in New Jersey’s K-12 Public Schools. Public Interest.

- Mincher JL, Symons CW, Thompson A (2012) A comparison of food policy and practice reporting between credentialed and noncredentialed Ohio school foodservice directors. J Acad Nutr Diet 112: 2035-2041.

- USDA (2013) National school lunch program. United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service.

- US Census Bureau (2014) State & county QuickFacts: Lincoln Parish, Louisiana. US Dep Commer Econ Stat Adm.

- Morgan DL (1997) Focus groups as qualitative research, (2nd edn). Qualitative research method. SAGE Publications, Inc., 16.

- Mayring P (2000) Qualitative content analysis. Forum Qual Soc Res 1: 2.

- Patton MQ (1987) How to use qualitative methods in evaluation, (2nd edn). SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA.

- Conk S, Lavigne J, Lindstrom M (2010) A school food revolution: Identifying and overcoming barriers to meaningful school lunch reform.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts (2013) Serving healthy school meals: kitchen equipment.

- (2001) School nutrition dietary assessment study - II. US Department of Agriculture.

- (2012) School nutrition dietary assessment study IV. US Department of Agriculture.

- Cohen JF, Richardson S, Austin SB, Economos CD, Rimm EB (2013) School lunch waste among middle school students: nutrients consumed and costs. Am J Prev Med 44: 114-121.

- Burden JE, Chomitz VR, Kim J, et al. (2004) Barriers to change in school food service as perceived by food service employees.

- Lloyd-Williams F, Bristow K, Capewell S, Mwatsama M (2011) Young children’s food in Liverpool day-care settings: a qualitative study of preschool nutrition policy and practice. Public Health Nutr 14: 1858-1866.

- (2010) S. 3307-111th Congress: Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010.

- Cho H, Nadow MZ (2004) Understanding barriers to implementing quality lunch and nutrition education. J Community Health 29: 421-435.

- (2014) Healthier US school challenge: Resources for getting started. US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition.

- McCullum-Gomez C, Barroso CS, Hoelscher DM, Ward JL, Kelder SH (2006) Factors influencing implementation of the coordinated approach to child health (CATCH) eat smart school nutrition program in Texas. J Am Diet Assoc 106: 2039-2044.