Journal of Oral Biology

Download PDF

Research Article

*Address for Correspondence: Shinya Mikushi, DDS, Department of Special Care Dentistry, Nagasaki University Hospital, 1-7-1 Sakamoto, Nagasaki 852-8501, Japan, Tel: +81-95-819-7717; Fax: +81-95-819-7715; E-mail: s394@nagasaki-u.ac.jp

Citation: Mikushi S, Chiba R, Fukushima A, Makiuchi A, Kitazawa C, et al. Videoendoscopic Evaluation of Saliva Aspiration in a Municipal Hospital. J Oral Bio. 2015;2(2): 4.

Copyright © 2015 Mikushi S, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Oral Biology | ISSN: 2377-987X | Volume: 2, Issue: 2

Submission: 24 August 2015 | Accepted: 07 September 2015 | Published: 10 September 2015

Reviewed & Approved by: Dr. Bronislaw L. Slomiany, Professor, Rutgers School of Dental Medicine, USA

Methods

Comparison by presence or absence of saliva aspiration

Videoendoscopic Evaluation of Saliva Aspiration in a Municipal Hospital

Shinya Mikushi1*, Ryuichi Chiba2, AkikoFukushima2, Atsuko Makiuchi2, Chie Kitazawa2, Tatsuya Honma2 and Takao Ayuse3

- 1Department of Special Care Dentistry, Nagasaki University Hospital, Japan

- 2Iida Hospital, Nagano, Japan

- 3Department of Clinical Physiology, Unit of Translational Medicine, Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Nagasaki, Japan

*Address for Correspondence: Shinya Mikushi, DDS, Department of Special Care Dentistry, Nagasaki University Hospital, 1-7-1 Sakamoto, Nagasaki 852-8501, Japan, Tel: +81-95-819-7717; Fax: +81-95-819-7715; E-mail: s394@nagasaki-u.ac.jp

Citation: Mikushi S, Chiba R, Fukushima A, Makiuchi A, Kitazawa C, et al. Videoendoscopic Evaluation of Saliva Aspiration in a Municipal Hospital. J Oral Bio. 2015;2(2): 4.

Copyright © 2015 Mikushi S, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Oral Biology | ISSN: 2377-987X | Volume: 2, Issue: 2

Submission: 24 August 2015 | Accepted: 07 September 2015 | Published: 10 September 2015

Reviewed & Approved by: Dr. Bronislaw L. Slomiany, Professor, Rutgers School of Dental Medicine, USA

Abstract

Videoendoscopic examination of swallowing is useful to examine for aspiration of saliva and food at the bedside. The purpose of the present study was to compare saliva aspiration to aspiration of food in patients with dysphagia. The subjects were 120 hospitalized patients (73 males, 47 females; mean age 82.8± 8.5 yrs) who underwent videoendoscopy. The presence of saliva aspiration, food (thick liquid of two different viscosities, thin liquid and solid food) aspiration, silent aspiration, and aspiration after swallowing were evaluated in each patient. Saliva aspiration was found in 41 (34.2%) patients. Aspiration of liquids with honey-like and nectar-like thicknesses was found in 28 (23.3%) patients and 48 (40.0%) patients, respectively. The total number of cases of aspiration of saliva and/or food was 104 (86.7%). Of these aspirators, silent aspiration was found in 44 (36.7%) patients, and aspiration after swallowing was found in 52 (43.3%) patients. Thick liquid was aspirated more frequently in patients with saliva aspiration. The proportion of silent aspiration and of aspiration after swallowing was higher in the saliva aspiration group. The results indicate that patients who aspirate saliva are also prone to food aspiration. But, there were patients who aspirated saliva but did not aspirate food. These patients were able to carry out direct therapy using thick liquid or other food adjusted properly. Food aspiration after swallowing may be induced by saliva aspiration.Keywords

Videoendoscopy; Deglutition disorders; Aspiration; Saliva; Silent aspirationIntroduction

Saliva contains large amounts of bacteria, and aspiration of saliva poses a risk of pneumonia. Aspiration of saliva and nasal secretions during sleep has been measured with methods using radioisotopes such as indium or technetium [1-4]. These studies report aspiration of saliva and nasal secretions in 10-100% of healthy persons, 70% of patients with depressed consciousness, 71% of patients with community-acquired pneumonia, and 100% of patients with chronic sinusitis and asthma. Saliva aspiration has also been found in 48% of patients under sedation with anesthetics [5], and aspiration of gastric contents was found in 8.3% of patients who did not vomit during surgery under general anesthesia [6]. With regard to saliva aspiration when awake, videoendoscopy carried out on 81 patients undergoing otolaryngological examination who did not complain of dysphagia showed saliva aspiration in two cases [7]. Saliva aspiration was reported in 12.1% of nursing home residents with dysphagia, and in 46% of outpatients with stable health and dysphagia [8]. Takahashi et al. reported that saliva aspiration is associated with pneumonia and weight loss; thus, improvement of saliva aspiration is important [8].Thorough oral care is important for improving oral hygiene to prevent pneumonia due to saliva aspiration, and training to improve saliva aspiration itself is also necessary. The likely causes of saliva aspiration are pharyngeal dysfunction that results in aspirating saliva as a liquid and reduction in sensory perception of the swallowing reflex and the cough reflex in response to saliva and its penetration to the larynx. Thus, saliva accumulates in the hypopharynx and trickles into the trachea during the swallowing reflex and in the intervals between the swallowing reflexes clinically. For patients with saliva aspiration, exercises without food (indirect therapy) are carried out to improve this pharyngeal function first. However, we sometimes encounter patients who can carry out training using food (direct therapy) even if they aspirate saliva. There have been few reports to date regarding the relationship between saliva aspiration and food aspiration. In this study, videoendoscopic examination of swallowing was used to compare saliva aspiration to aspiration of thick liquid with two types of viscosity (nectar-like and honey-like) and other food in patients with dysphagia hospitalized in municipal hospitals.

Materials and Methods

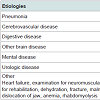

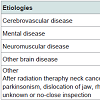

SubjectsSubjects included 124 patients who were hospitalized at Iida Hospital in Nagano Prefecture between September 2011 and September 2013 who had dysphagia and underwent videoendoscopic examination of swallowing. Four patients who underwent tracheotomy were excluded, giving a final total of 120 patients (73 males, 47 females; mean age 82.8 ± 8.5 yrs, age range 56-98 yrs). The most common reason for hospitalization was pneumonia, accounting for half of the patients, followed by cerebrovascular disease (Table 1). The most common primary disease underlying dysphagia was cerebrovascular disease (Table 2). The nutritional route was oral ingestion alone in 31 patients, combined oral ingestion and tube feeding in 32 patients, and tube feeding alone in 57 patients. Of the 89 patients who took nutrition via tube feeding, 8 were fed through a gastrostomy tube and 8 through a nasogastric tube.

Methods

The age, sex, primary disease, prior diseases, nutritional route, presence of saliva aspiration, presence of food aspiration, presence of silent aspiration and presence of aspiration after swallowing for each patient were extracted retrospectively from the database of the results of videoendoscopic examination of swallowing. Saliva aspiration was rated as present if flow of saliva into the trachea was confirmed visually by a dentist and two speech language therapists at the start of videoendoscopy. Two types of thick liquid were ingested during videoendoscopy, nectar-like and honey-like. The viscosity was adjusted by adding water to thickening agent (Neo Hightoro Meal R&E, Food Care, Kanagawa, Japan) to nectar-like (200-300 mPa·s) and honey-like (400-500 mPa·s) viscosity. The liquid used during videoendoscopy was colored with green food coloring, 4 mL of thick liquid were placed in the oral vestibule using a syringe, and the patients swallowed the formula in their own time. Patients also ingested various volume of thin liquid or solid food, depending on their severity of dysphagia, during videoendoscopy. Cases in which there was no cough reflex or any reaction to expectorate the aspirated matter after confirmation of liquid or food aspiration were judged to be silent aspiration. Aspiration following swallowing was rated as pharyngeal residue aspirate after the swallowing reflex.

Statistical analysis

The patients were divided into two groups on the basis of the presence or absence of saliva aspiration, and the other items were compared. An independent two-sample t-test was carried out to compare the mean ages of the two groups. A chi-squared test was used to compare the presence of saliva aspiration by sex, presence of food aspiration, presence of silent aspiration, and presence of aspiration after swallowing. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

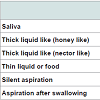

Saliva and food aspirationSaliva aspiration was found in 41 of 120 patients. Aspiration of honey-like thick liquid was found in 28 patients, and aspiration of nectar-like thick liquid was found in 48 patients. The total number of cases of aspiration of liquid and/or food during videoendoscopy was 104. Of these aspirators, silent aspiration was found in 44 patients, and aspiration after swallowing was found in 52 patients (Table 3).

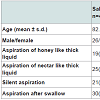

Comparison by presence or absence of saliva aspiration

The mean age of participants was 82.8 ± 8.5 years for the saliva aspiration group and 82.9 ± 9.0 years for the no saliva aspiration group, with no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.97, t-test). The saliva aspiration group consisted of 26 males and 15 females, and the no saliva aspiration group consisted of 47 males and 32 females, with no significant difference between the groups (chisquared test, p = 0.70). The honey-like thick liquid was aspirated by 19 patients in the saliva aspiration group and by 9 patients in the no saliva aspiration group, with the proportion of aspiration significantly higher in the saliva aspiration group (chi-squared test, p < 0.001). Similarly, the nectar-like liquid was aspirated by 25 patients in the saliva aspiration group and by 23 patients in the no saliva aspiration group, with the proportion of aspiration significantly higher in the saliva aspiration group (chi-squared test, p < 0.001). The proportions of silent aspiration and of aspiration after swallowing were higher in the saliva aspiration group (chi-squared test, p = 0.03, p < 0.001 respectively) (Table 4).

Discussion

Aspiration of salivaSaliva aspiration by healthy persons during non-waking time has been shown by studies using radioisotopes with sleeping subjects [1-4]. Aspiration of even minute amounts of saliva can be detected using radioisotopes, but videoendoscopic examination of swallowing also allows visual examination of saliva aspiration [7-9]. In the present study, aspiration when awake was found in 41 of 120 cases (34.2%). Takahashi et al. carried out videoendoscopic examination of swallowing in 148 elderly residents of nursing care facilities (age 85.1 ± 8.0 years) that consumed food orally and were suspected of having dysphagia from a questionnaire [8]. They reported that saliva aspiration was found by videoendoscopy in 18 people (12.2%), and that subsequent follow-up showed that saliva aspiration was a factor in pneumonia and weight loss. Schröter-Morasch et al. carried out videoendoscopic examination of swallowing in 39 neurogenic dysphagia patients (age range 21-79 years, median age 57 years) with stable physical conditions and good understanding of instructions [9]. They reported saliva aspiration in 18 of the 39 patients (46%). The present results show a different proportion of saliva aspiration than either of these two studies, but the level of consciousness and the level of dysphagia of the subjects differed in each study such that direct comparisons cannot be made.

Relationship between saliva aspiration and food aspiration

In the present study, aspiration was investigated with thick liquid of two levels of viscosity, and aspiration was found in many patients who aspirated saliva. The results indicate that patients who aspirate saliva are also prone to food aspiration. Possible causes of saliva aspiration are pharyngeal dysfunction that aspirates saliva as a liquid, and reduced sensation leading to a lack of the swallowing reflex even when saliva accumulates in the pharynx; seemingly to also lead to food aspiration. Cases of reduced function in which saliva accumulates in the pharynx are likely to be the result of impaired pharyngeal clearance due to incomplete pharyngeal constriction or impaired opening of the upper esophageal sphincter, or else sensory decline, such as delay of the swallowing reflex or an increased threshold level of the cough reflex [10]. We intend to examine the characteristics of functional reduction in patients with saliva aspiration by videofluorographic evaluation of swallowing (VF) in the future. There were many patients who showed aspiration after swallowing among patients with saliva aspiration. Smith et al. reported that aspiration after swallowing is the most frequent timing of aspiration [11], and in the present study, aspiration after swallowing was found in 50% of cases that aspirated. In cases in which saliva accumulates as a result of pharyngeal dysfunction, food is likely to accumulate in the pharynx in the same way; and clinically, there have been many cases in which food and saliva that accumulated in the pyriform sinus flowed into the trachea together, such that food aspiration after swallowing is induced by saliva aspiration.

Nonetheless, there were patients who aspirated saliva but did not aspirate the thick liquid. These patients were able to carry out direct therapy using thick liquid and to take food in paste form with the viscosity adjusted. For some patients their saliva may be more difficult to swallow than thick liquid with proper viscosity. We intend to investigate the relationship between the characteristics of saliva and saliva aspiration in the future.

Silent aspiration

Silent aspiration was found in 44 (42.3%) of the 104 patients in whom aspiration was present. Takahashi et al. reported silent aspiration in 19 (31.7%) of 60 patients who aspirated food [8]. Leder et al. carried out videoendoscopic examinations of swallowing in 400 inpatients, and found aspiration in 225 patients (56.3%), of whom 110 (48.9%) showed silent aspiration [12]. Garon et al. carried out VF of 2,000 inpatients, and found aspiration in 51%, of whom 55% showed silent aspiration [13]. Rosenbek et al. defined silent aspiration as when material enters the airway, passes below the vocal folds, and no effort is made to eject it [14]. Blitzer et al. defined silent aspiration as the passage of food or liquids through and below the level of the true vocal folds, without producing a reflexive cough or other overt sign that aspiration has occurred [15]. In the present study, cases in which food, regardless of the amount, passed the vocal cords and entered the trachea with no coughing were considered to be silent aspiration. However, Leder et al. reported that silent aspiration is affected by the amount of aspiration [16]. There are also patients in whom coughing is considerably delayed, so a definition of silent aspiration that includes the time from aspiration until coughing is needed. Silent aspiration is common among patients who aspirate saliva, and it appears that saliva aspiration is furthered by a reduction in laryngeal sensation, such as the swallowing reflex or the cough reflex. In the present study, patients with tracheotomy were excluded. Aspiration in tracheotomy patients is often silent, and these patients are at high risk of saliva aspiration [17]. We intend to examine the relationship between tracheotomy and aspiration in the future with a larger number of cases.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study was carried out with the approval of the ethics review committee of Nagasaki University Hospital. The experiments were undertaken with the understanding and written consent of each subject and according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their profound gratitude to the members of the Nutrition Support Team of Iida Hospital for their assistance with videoendoscopic evaluation of swallowing.References

- Huxley EJ, Viroslav J, Gray WR, Pierce AK (1978) Pharyngeal aspiration in normal adults and patients with depressed consciousness. Am J Med 64: 564-568.

- Kikuchi R, Watabe N, Konno T, Mishina N, Sekizawa K, et al. (1994) High incidence of silent aspiration in elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 150: 251-253.

- Gleeson K, Eggli DF, Maxwell SL (1997) Quantitative aspiration during sleep in normal subjects. Chest 111: 1266-1272.

- Ozcan M, Ortapamuk H, Naldoken S, Olcay I, Ozcan KM, et al. (2003) Pulmonary aspiration of nasal secretions in patients with chronic sinusitis and asthma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 129: 1006-1009.

- Savilampi J, Ahlstrand R, Magnuson A, Geijer H, Wattwil M (2014) Aspiration induced by remifentanil: a double-blind, randomized, crossover study in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology 121: 52-58.

- Culver GA, Makel HP, Beecher HK (1951) Frequency of aspiration of gastric contents by the lungs during anesthesia and surgery. Ann Surg 133: 289-292.

- Nishiyma K, Nagai H, Usui D, Kurihara R, Yao K, et al. (2010) Screening test for dysphagia in the elderly. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho 113: 542-548.

- Takahashi N, Kikutani T, Tamura F, Groher M, Kuboki T (2012) Videoendoscopic assessment of swallowing function to predict the future incidence of pneumonia of the elderly. J Oral Rehabil 39: 429-437.

- Schröter-Morasch H, Bartolome G, Troppmann N, Ziegler W (1999) Values and limitations of pharyngolaryngoscopy (transnasal, transoral) in patients with dysphagia. Folia Phoniatr Logop 51: 172-182.

- Linden P, Seibens AA (1983) Dysphagia: predicting laryngeal penetration. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 6: 281-284.

- Smith CH, Logemann JA, Colangelo LA, Rademaker AW, Pauloski BR (1999) Incidence and patient characteristics associated with silent aspiration in the acute care setting. Dysphagia 14: 1-7.

- Leder SB, Bayar S, Sasaki CT, Salem RR (2007) Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing in assessing aspiration after transhiatal esophagectomy. J Am Coll Surg 205: 581-585.

- Garon BR, Sierzant T, Ormiston C (2009) Silent aspiration: results of 2,000 video fluoroscopic evaluations. J Neurosci Nurs 41: 178-185.

- Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, Coyle JL, Wood JL (1996) A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia 11: 93-98.

- Blitzer A (1990) Approaches to the patient with aspiration and swallowing disabilities. Dysphagia 5: 129-137.

- Leder SB, Suiter DM, Green BG (2011) Silent aspiration risk is volume-dependent. Dysphagia 26: 304-309.

- Leder SB (2002) Incidence and type of aspiration in acute care patients requiring mechanical ventilation via a new tracheotomy. Chest 122: 1721-1726.