Journal of Surgery

Download PDF

Editorial

Stump Appendicitis and the Critical View of Safety

Eoghan P. Burke*, Salama M, Saeed M, Ahmed I

Department of Surgery, Ireland

*Address for Correspondence:

Eoghan P. Burke, Department of Surgery, Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital,

Drogheda, Ireland, E-ma.il: eoghanburke@rcsi.ie

Submission: 26 June, 2019;

Accepted: 03 July, 2019;

Published: 05 July, 2019

Copyright: © 2019 Burke EP. This is an open access article distributed

under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided

the original work is properly cited.

Editorial

We present a case of a 27-year-old gentleman who presented to

our hospital. He underwent a laparoscopic appendectomy six months

previously. His surgery was complicated by a post-operative collection

which was drained under CT guidance. He had no past medical

history and was on no regular medication. He presented with a one

day history of Right Iliac Fossa (RIF) pain. The pain was constant, dull

in nature and was progressively getting worse. It was associated with

anorexia, nausea and two episodes of vomiting. He denied rigors,

diarrhoea, constipation or urinary tract symptoms. On examination,

he was febrile (39 o

C), his abdomen was soft but tender in the RIF

with guarding. His laboratory investigations were significant for a

C-reactive protein level of 32 mg/L and a white cell count of 14x109/L.

The differential included a post-operative collection. He underwent a

CT scan of his abdomen and pelvis.

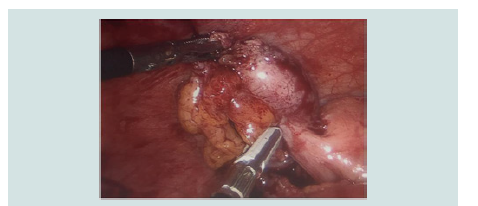

The CT scan showed a thickened oedematous wall of the inferior

pole of the cecum along with an appendicular stump which was

acutely inflamed (Figure 1). The patient underwent laparoscopy in

which an acutely inflamed appendicular stump was seen (Figure 2). It was successfully resected. The patient recovered well and was

discharged home on post-operative day 2. He has reported no further

complications at his 3-month review clinic.

Acute appendicitis is one of the most common indications for

emergency abdominal surgery accounting for approximately 1% of all

surgical operations. Common post-operative complications include

wound infections, intra-abdominal infections and adhesions. The first

two cases of stump appendicitis were reported by Rose et al in 1945

[1]. The precise pathogenesis remains poorly understood, however

it is postulated that obstruction of the remaining stump lumen by

a fecolith may be the causative factor. This increases intraluminal

pressure, impairs venous drainage and allows subsequent bacterial

infection. There are approximately 62 cases reported in the literature

although most authors would suggest that it is underreported. Most

reported cases do not have radiographic or photo-documentation of the appendicular stump being acutely inflamed.

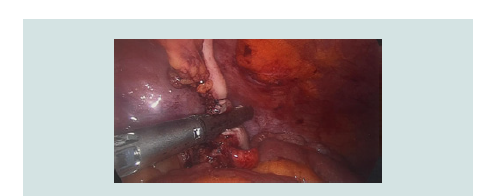

Figure 2: Intraoperative image from completion appendectomy. Identifies

appendicular stump measuring greater than the recommended 5 mm.

Stump appendicitis was traditionally felt to be more common

following a laparoscopic appendectomy secondary to the absence of

tactile feedback and a 3-dimensional perspective. However, the most

extensive review to date on the topic conducted by Subramanian et

al disproved this theory and found it to be more common in open

appendectomies [2].

Multiple factors are thought to contribute to incomplete

appendectomy, the most important being incorrect identification of

the surgical anatomy. This led Subramanian et al to propose A Critical

View of Safety (CVS) for appendectomy similar to that famously

developed by Strasberg et al in 1995 for laparoscopic cholecystectomy

[2]. This CVS for appendectomy centres on correctly identifying the

appendicular-cecal junction and thus the appendicular base. The CVS

is achieved when the taenia libera is seen clearly on the surface of

the cecum running into the base of the appendix with the appendix

elevated and displaced inferiorly and the terminal ileum in the

foreground at laparoscopy. In this position, the mesoappendix can

then be divided appropriately and the base clearly identified.

The length of the appendicular stump left behind is crucial. Most

authors recommend leaving less than 5mm behind. A stump of

greater than 5mm is thought to be large enough to act as a reservoir

for a fecolith [3]. In Figure 3 we depict an intraoperative image from

our patient’s initial laparoscopic appendectomy (Figure 3). We can

see that the CVS has not been identified. This led the surgeon to

incorrectly assume he had identified the appendicular base leading

him to leave a stump of greater than 5 mm behind.

Figure 3: Intraoperative image from initial laparoscopic appendectomy. Endo

GIA fired too high secondary to inadequate visualisation of appendicular

base.

Stump appendicitis continues to pose a diagnostic dilemma

both for surgeons and emergency department clinicians. We quickly

remove acute appendicitis from our differential diagnosis list in patients presenting with RIF pain when we learn they have had

previous appendectomy. The temporal relationship between index

appendectomy and onset of stump appendicitis is hugely variable

ranging from weeks to years which further complicates matters.

We can aim to limit the risk of stump appendicitis by encouraging

surgeons to adopt the CVS for appendectomy suggested by

Subramanian et al.